In the nearly seven months since President Trump took office again, academic associations, faculty unions, researchers and other groups have used the legal system to push back on the administration’s efforts to reshape higher education and the federal government.

So far, district and appeals courts have largely suggested that the executive branch’s actions are unconstitutional and ruled in favor of university advocates, handing down preliminary injunctions, restraining orders and a few final judgments that have blocked the Trump administration’s goals. But based on the few cases that have reached the Supreme Court, some higher education experts worry the tide may be turning, and the high court’s conservative majority will ultimately side with the president.

The lawsuits challenged bans on diversity, equity and inclusion programs; the administration’s crackdown on international students; the termination of thousands of grants; and the dismantling of the Department of Education.

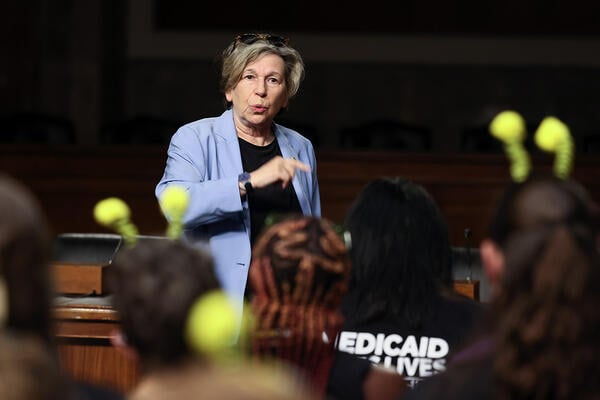

“What we’re seeing is that when the administration tries to impose a whole new set of rules and regulations based upon their particular ideology … the courts are saying, ‘Wait’ or ‘No,’ until it gets to the Supreme Court,” said Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, a teachers’ union that has filed multiple lawsuits against Trump and notched a few victories.

An Inside Higher Ed analysis of more than 40 lawsuits against the administration that are related to higher ed found that district judges have ruled against the executive branch in nearly two-thirds of the cases. Almost a quarter have yet to be decided. Of those in which a judge has ruled, 18 have been appealed, and only two were overturned. In both instances when the district court was overruled, it had to do with reversing injunctions that prevented the Trump administration from canceling grants based in part on the president’s executive order against DEI. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Trump administration in a separate but similar case.

Nine cases have yet to receive a decision from an appeals court.

For more updates on litigation against the administration, go to Inside Higher Ed revamped lawsuit tracker. The searchable database will be updated regularly.

Of the cases Inside Higher Ed analyzed, the most frequent issue at hand was grant cuts, at 14 cases, followed by the Education Department’s reduction in force at eight.

“A lot of the actions the administration is taking are very clearly being defined by the courts as patently illegal. They’re outside of the established law and they exceed executive authority,” said Jon Fansmith, senior vice president for government relations at the American Council on Education, which has sued the administration several times to challenge a proposed cap on reimbursements for indirect research expenses that would cost universities millions.

Few cases that Inside Higher Ed is tracking have reached the Supreme Court, but so far the justices have overturned lower court rulings in three, allowing the Education Department to proceed with mass layoffs and to cut millions in grants for teacher training. They haven’t reached a decision in the other two cases, which are challenging grant cuts at the National Institutes of Health.

Some worry that rulings from the conservative majority on the Supreme Court could be driven by party alignment more than the law. Fansmith said he was certainly concerned by the court’s rulings so far but was hesitant to call them an “interjection of partisan politics.”

He noted that the rulings have come from the court’s shadow docket. This means they have made their decisions outside of the traditional case procedures with limited briefings, no oral argument and often no detailed explanations.

For example, when it comes to the case challenging the Education Department’s layoffs, Fansmith said that the lawyers he’s talked to are “sort of confounded by the decision.” The justices didn’t offer an opinion on whether the department can legally fire half its employees, but did allow the administration to proceed with the process while the courts work through the case.

“So it’s sort of a split decision in some ways; the merits haven’t yet been resolved finally,” he said.

But the odds of the court making a final judgment that brings back the employees seems unlikely, some legal experts have said. And Weingarten noted that even if they do hear the cases this fall and make a final decision next spring, the damage will have been done.

“The problem is that when you start talking about medical and scientific research, the moment that those things get stopped, there is irreparable damage and it’s hard to recreate them,” she said. “The Trump administration is really hurting what was an anchoring principle of American enterprise and innovation … that research has really been suffocated and used as leverage for the Trump administration to get its ideological whims adopted.”

Still, many different plaintiffs—including Democratic attorneys general—continue to push back against the Trump administration’s agenda.

Massachusetts AG Andrea Joy Campbell, who has challenged the president in multiple suits, believes that Trump and his cabinet have repeatedly demonstrated a willingness to use “unlawful abuses of power” to limit academic freedom. And as long as they continue to do so, she added, Democratic leaders will keep taking matters to court.

“State attorneys general have the power to fight back to uphold the rule of law and protect our young people—and that’s exactly what we’re doing,” Campbell wrote in an email to Inside Higher Ed. “We’ve achieved significant victories in the vast majority of our cases, and we will continue to hold the line because our children and the future of our democracy depend on it.”

Democracy Forward, a nonprofit legal group that has represented plaintiffs in a number of cases, also chimed in, saying the Trump-Vance “assault” on education will continue to be “met with force.”

“These victories show just how essential higher education is to our democracy and why protecting it from political interference will remain a core part of our work,” said Skye Perryman, the group’s president and CEO.

She added that while the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn some cases was “incredibly disappointing,” it’s not the end.

“We win a lot, but if we’re not experiencing some setbacks, we’re not pushing hard enough,” she said.

However, major concerns still loom among many higher education advocates as Trump officials continue to fight back, pushing for lawsuits to reach the Supreme Court and lambasting the district and appellate judges that rule against the executive branch, calling them “activist[s]” for disagreeing with the president.

“There is a troubling and dangerous trend of unelected judges inserting themselves into the presidential decision-making process,” White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt said during a press conference in May.

Leavitt’s comments were related to court decisions blocking certain immigration policies, but Madi Biedermann, press secretary for the Education Department, has also criticized judges that rule against Trump.

In May, Biedermann called a district court judge who blocked the department’s mass layoffs a “far-left judge,” adding that he “dramatically overstepped his authority” and had “a political ax to grind.”

Weingarten, on the other hand, says it’s Trump and the conservative Supreme Court that are thwarting academic freedom and violating constitutional rights for political power.

What we’ve seen is “more the sign of an autocrat that tries to control as opposed to people who believe in freedom,” she said. “It’s all very, very dangerous for the future of America.”