[For my good friend, a higher education executive who has seen it all, and suggested that all of us pause, take a look back, and think.]

Neil Postman first gained national attention in 1969 with Teaching as a Subversive Activity, co-authored with Charles Weingartner. In a period marked by war, civil unrest, and cultural transformation, Postman offered a bold challenge to the status quo of American education. Schools, he argued, were failing not because they lacked resources or rigor, but because they had lost sight of their deeper purpose. Instead of fostering critical thinking and civic engagement, they were manufacturing conformity through standardized tests, textbooks, and passive learning. Postman envisioned classrooms without fixed curricula, where teachers would become co-learners and facilitators, helping students develop the tools of inquiry and what he memorably called “crap detection.” It was a radical vision: education as an act of democratic resistance.

By the early 1980s, Postman had turned his attention to how media was shaping society—and deforming education. In The Disappearance of Childhood (1982), he claimed that television was dissolving the cultural boundaries between children and adults. Television, unlike print, made no distinction in content delivery; it treated all viewers as equal consumers of images and sensation. The consequences, he warned, were profound: children were becoming prematurely cynical while adults increasingly behaved like children. The medium, he believed, flattened developmental distinctions and eroded the cultural function of school as a place for guided maturation and ethical formation.

Then came Amusing Ourselves to Death in 1985, Postman’s most widely read and enduring work. Written during the ascendancy of television and Reagan-era consumer culture, the book argued that television had transformed public discourse into entertainment. It was not merely the content of television that disturbed him, but its form—its bias toward speed, simplification, and emotional stimulation. In such a media environment, serious discussion of politics, education, science, or religion could not survive. News became performance, candidates became celebrities, and education was increasingly judged by its entertainment value. Postman lamented the way Sesame Street, often hailed as educational television, conditioned children to love television itself—not learning, not schools, not the slow, difficult process of study.

As the decade progressed, Postman began articulating a broader cultural critique that culminated in Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology (1992). In this work, he defined technopoly as a society that not only uses technology but is dominated by it—a culture that believes technology is the solution to all problems, and that all values should be reshaped in its image. Postman acknowledged that tools and machines had always altered human life, but in a technopoly, technology becomes self-justifying. It no longer asks what human purpose it serves. Postman noted that schools were being wired with computers, not because it improved learning—there was no solid evidence of that—but because it seemed modern, inevitable, and profitable. His question—“What is the problem to which this is the solution?”—was a challenge not just to education reformers, but to an entire ideology of progress.

In The End of Education (1995), Postman returned to the question that haunted all his work: what is school for? He argued that American education had lost its narrative. Without compelling guiding stories—what he called “gods”—schools could not inspire loyalty, discipline, or moral development. In place of narratives about democracy, stewardship, public participation, and truth-seeking, schools now told the story of market utility. They trained students for jobs, not for life. They emphasized performance metrics over philosophical inquiry, and they treated students as customers in a credential economy. Education, he warned, was becoming just another mass medium, modeled increasingly after television and later the internet, with predictable results: shallowness, fragmentation, and disengagement.

By the time Postman died in 2003, the world he had warned about was rapidly taking shape. Facebook had not yet launched. Smartphones had not yet arrived. Generative AI was decades from the mainstream. But already, education was being reshaped by branding, performance metrics, digital delivery, and venture capital. The university was becoming a platform. The classroom was being converted into content. Students were treated not as citizens in formation, but as users to be optimized. The language of education—once rooted in moral philosophy and civic purpose—had begun to sound more like business strategy. Postman would have heard the rise of terms like “learning outcomes,” “human capital development,” and “scalable solutions” as evidence of a culture that had surrendered judgment to systems, wisdom to code, and meaning to metrics.

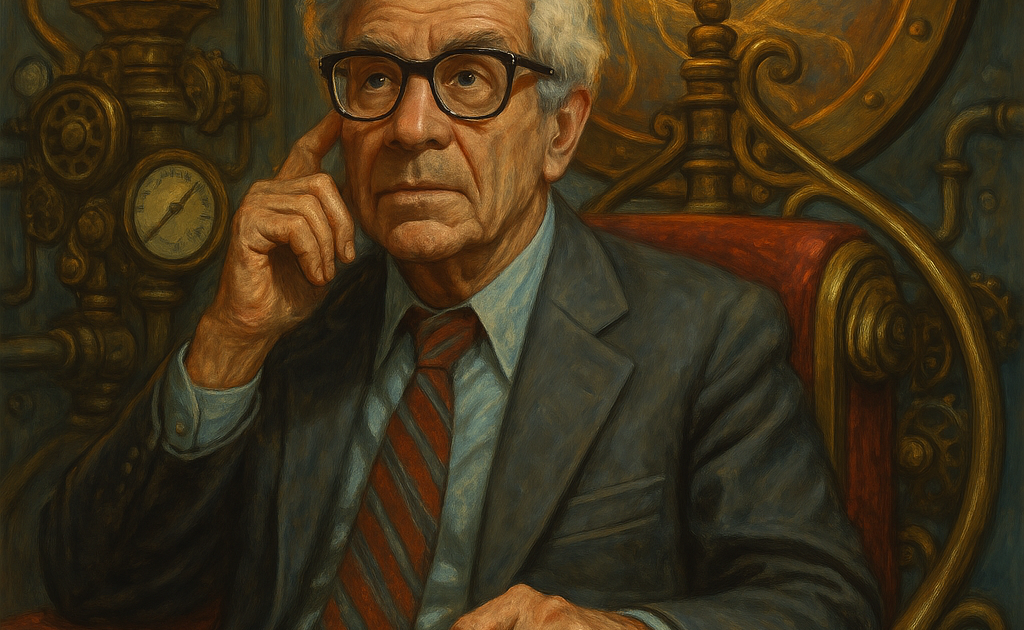

Postman’s refusal to embrace digital culture made him easy to ignore in the years that followed. He never gave a TED Talk. He didn’t blog. He didn’t build a brand. He never even used a typewriter. He wrote every word by hand. In a world of media influencers, LinkedIn thought leaders, and edtech evangelists, Postman’s ideas didn’t fit. But the deeper reason we forgot him is more unsettling.

Remembering Postman would require a painful reckoning with how far higher education has drifted from its public mission and democratic roots. It would mean admitting that education has been refashioned not as a sacred civic institution but as a delivery mechanism for marketable credentials. It would mean asking questions we’ve tried hard to bury.

What is higher education for? What kind of people does it produce? Who decides its purpose? What stories do our schools still tell—and whose interests do those stories serve?

Postman would not call for banning screens or abolishing online learning. He was not nostalgic for chalkboards or print for their own sake. But he would demand that we pause, reflect, and resist. He would ask us to think about what kind of citizens our institutions are shaping, and whether the systems we’ve built still serve a human purpose. He would remind us that information is not wisdom, and that no innovation can substitute for meaning.

As the Higher Education Inquirer continues its investigations into the commercialization of academia, the credentialing economy, and the collapse of higher ed’s public trust, we find Postman’s voice echoing—uninvited but indispensable. His critiques were not popular in his time, and they are even less welcome now. But they are truer than ever.

We may have forgotten him. But we are living in the world he tried to warn us about.

Sources

Neil Postman and Charles Weingartner, Teaching as a Subversive Activity (1969)

Neil Postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death (1985)

Neil Postman, Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology (1992)

Neil Postman, The End of Education: Redefining the Value of School (1995)

Postman’s archived writings: https://web.archive.org/web/20051102091154/http://www.bigbrother.net/~mugwump/Postman/