All of the vile executive orders issued by the Trump administration against law firms refer to purported “significant risks” associated with them, and have the same whiff of oppression:

Below the veneer of such boilerplate claims lies a repressive truth: they’re designed to be punitive, and to produce a fear that leads to robotic subservience. They are but a part of Trump’s enemies list. And his orders are to be executed by his lackey Attorney General Pam Bondi — the same person who once said: “I will fight every day to restore confidence and integrity to the Department of Justice and each of its components. The partisanship, the weaponization will be gone.”

Against that backdrop comes a courageous group of lawyers and press groups led Andrew Sellers, with Mason Kortz joined by Kendra K. Albert as local counsel.

Mr. Sellers filed the amicus brief on behalf of 61 media organizations and press freedom advocates in the case of Perkins Coie v. U.S. Department of Justice. At the outset he exposes the real agenda of the authoritarian figure in the White House:

“The President seeks the simultaneous power to wield the legal system against those who oppose his policies or reveal his administration’s unlawful or unethical acts—who, in many cases, have been members of the press—and then deny them access to the system built to defend their rights. The President could thus ‘permit one side to have a monopoly in expressing its views,’ which is the “antithesis of constitutional guarantees.’”

Mr. Sellers reminds us that “‘freedom of the press holds an . . . exalted place in the First Amendment firmament,’ because the press plays a vital role in the maintenance of democratic governance. To fulfill that function, the press relies on the work of lawyers. Lawyers assist the press in obtaining access to records and government spaces . . . because the press plays a vital role in the maintenance of democratic governance.”

To honor that principle, Sellers argues that “the press relies on the work of lawyers. Lawyers assist the press in obtaining access to records and government spaces. They advise the press on how to handle sensitive sources and content. And they defend the press against civil and criminal threats for their publications.”

Among other key points made in this important brief is the following one:

If the Executive Order stands, many lawyers will be chilled from taking on work so directly in conflict with the President, out of fear for the harm it would cause to their clients whose relationship with the government is more transactional. For the lawyers that remain, the threat of a similar executive order aimed at them or their law firms would practically prevent them from doing their jobs, by denying their access to the people and places necessary to adjudicate their issues.

The project was spearheaded by The Press Freedom Defense Fund (a project of Intercept) and the Freedom of the Press Foundation.

Some of the lawyers who signed this amicus brief include Floyd Abrams, Lee Levine, Seth Berlin, Ashley Kissinger, Elizabeth Koch, Lynn B. Oberlander, David A. Schulz, and Charles Toobin.

The Table of Contents appears below:

Introduction & Summary of Argument

Interests of Amici

Argument

- A Free Press Allows the Public to Check Overreaching Government but Requires Legal Support.

- The Oppositional Role of the Press Will Not Function if the Court Allows This executive order.

- The government will inevitably use this authoritarian power to target the press.

- The executive order will chill lawyers from working with the press.

- The lawyers that remain will be unable to do their jobs.

- Without a Robust Press, the Public will Lose a Key Vindicator of First Amendment Rights.

Related

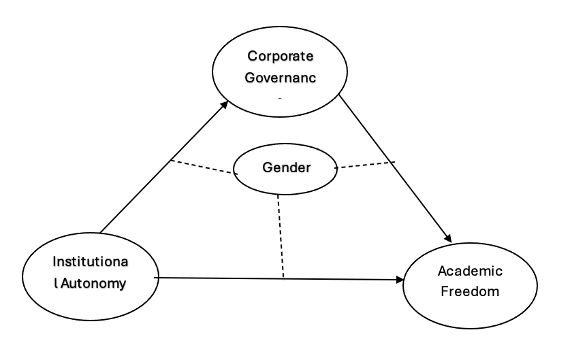

Pronoun punishment policy in the Trump administration

You know those email signatures at the end of messages? The ones that include a range of information about the senders — phone numbers, addresses, social media handles. And in recent years, pronouns — letting the recipient know that the sender goes by “she,” “he,” “they” or something else, a digital acknowledgement that people claim a range of gender identities.

Among those who don’t agree with that are President Donald Trump and members of his administration. They have taken aim at what he calls “gender ideology” with measures like an executive order requiring the United States to recognize only two biological sexes, male and female. Federal employees were told to take any references to their pronouns out of their email signatures.

That stance seems to have spread beyond those who work for the government to those covering it. According to some journalists’ accounts, officials in the administration have refused to engage with reporters who have pronouns listed in their signatures.

The New York Times reported that two of its journalists and one at another outlet had received responses from administration officials to email queries that declined to engage with them over the presence of the pronouns. In one case, a reporter asking about the closure of a research observatory received an email reply from Karoline Leavitt, the White House press secretary, saying, “As a matter of policy, we do not respond to reporters with pronouns in their bios.”

Dare one ask? Is pro-Palestinian speech protected?

Shortly after his inauguration, President Donald Trump vowed to combat antisemitism on U.S. college and university campuses, describing pro-Palestinian activists and protesters as “pro-Hamas,” and threatening to revoke their visas.

The first target of these threats was Mahmoud Khalil, a pro-Palestinian activist and former student of Columbia University, who was a negotiator for Columbia students during talks with university officials regarding their tent encampment last spring, according to The Associated Press.

Since his arrest, more than half a dozen scholars, professors, protesters and students have had their visas revoked with threats of deportation. Two opted to leave the country on their own terms, unsure of how legal proceedings against them would play out.

Free speech and civil liberties organizations have raised concerns over the arrests, claiming the Trump administration is targeting pro-Palestinian protesters for constitutionally protected political speech because of their viewpoints.

[ . . . ]

First Amendment Watch spoke with Esha Bhandari, deputy director of the ACLU’s Speech, Privacy and Technology Project, about the First Amendment implications of the Trump administration’s alleged targeting of pro-Palestinian protesters and activists. Bhandari explained how actions taken under the Immigration and Nationality Act need to be consistent with the First Amendment, described the importance of the right to peacefully assemble, and expressed that all Americans, regardless of their viewpoint, should be concerned with the Trump administration’s actions and its chilling of speech.

[Interview follows]

David Cole on the war on the First Amendment

Just released: Oxford University Press handbook on free speech

Freedom of speech is central to the liberal democratic tradition. It touches on every aspect of our social and political system and receives explicit and implicit protection in every modern democratic constitution. It is frequently referred to in public discourse and has inspired a wealth of legal and philosophical literature. The liberty to speak freely is often questioned; what is the relationship between this freedom and other rights and values, how far does this freedom extend, and how is it applied to contemporary challenges?

“The Oxford Handbook on Freedom of Speech” seeks to answer these and other pressing questions. It provides a critical analysis of the foundations, rationales, and ideas that underpin freedom of speech as a political idea, and as a principle of positive constitutional law. In doing so, it examines freedom of speech in a variety of national and supranational settings from an international perspective.

Compiled by a team of renowned experts in the field, this handbook features original essays by leading scholars and theorists exploring the history, legal framework, and controversies surrounding this tenet of the democratic constitution.

Forthcoming book on free speech and social media platforms

Why social media platforms have a responsibility to look after their platforms, how they can achieve the transparency needed, and what they should do when harms arise.

The large, corporate global platforms networking the world’s publics now host most of the world’s information and communication. Much has been written about social media platforms, and many have argued for platform accountability, responsibility, and transparency. But relatively few works have tried to place platform dynamics and challenges in the context of history, especially with an eye toward sensibly regulating these communications technologies.

In ”Governing Babel,” John Wihbey articulates a point of view in the ongoing, high-stakes debate over social media platforms and free speech about how these companies ought to manage their tremendous power.

Wihbey takes readers on a journey into the high-pressure and controversial world of social media content moderation, looking at issues through relevant cultural, legal, historical, and global lenses. The book addresses a vast challenge — how to create new rules to deal with the ills of our communications and media systems — but the central argument it develops is relatively simple. The idea is that those who create and manage systems for communications hosting user-generated content have both a responsibility to look after their platforms and have a duty to respond to problems. They must, in effect, adopt a central response principle that allows their platforms to take reasonable action when potential harms present themselves. And finally, they should be judged, and subject to sanction, according to the good faith and persistence of their efforts.

Franks and Corn-Revere to discuss ‘Fearless Speech’

Coming this Thursday over at Brooklyn Law School:

Book Talk: Dr. Mary Anne Franks’ Fearless Speech

Featuring:

Dr. Mary Anne Franks

Eugene L. and Barbara A. Bernard Professor in Intellectual Property, Technology, and Civil Rights Law, George Washington Law School; President and Legislative & Tech Policy Director, Cyber Civil Rights InitiativeRobert Corn-Revere

Chief Counsel, Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE)Moderators

William Araiza, Stanley A. August Professor of Law, Brooklyn Law School

Joel Gora, Professor of Law, Brooklyn Law School

Discussants

Ron Collins, Co-founder of the History Book Festival and former Harold S. Shefelman Scholar, University of Washington Law School

Sarah C. Haan, Class of 1958 Uncas and Anne McThenia Professor of Law, Washington and Lee University School of Law

Lukianoff’s TED talk

Last Wednesday, FIRE’s Greg Lukianoff delivered his first TED talk at TED 2025 in Vancouver. He spoke on why so many young people have given up on free speech and how to win them back. As he noted in a recent post for his Substack newsletter, The Eternally Radical Idea:

“After months of seemingly endless writing, rewriting, and rehearsing, I’m very happy with how it turned out! (Many thanks to Bob Ewing, Kim Hemsley, Maryrose Ewing, and Perry Fein for helping me prepare. Couldn’t have done it without them!)

We’re not yet sure when the full talk will be available online, but we’ll keep you posted!”

‘So to Speak’ podcast: The plight of global free speech

We travel from America to Europe, Russia, China, and more places to answer the question: Is there a global free speech recession?

Guests:

More in the news

- Leila Fadel, “How the Trump administration is impacting the First Amendment rights of scientists,” NPR (April 14)

- Anvar Ruziev, “Drag Show Denied: Naples Pride fights back with First Amendment lawsuit,” Fox 4 (April 14)

- Dawne Wolfe, “Rising Wave of Funders and PSOs Stand Up for the First Amendment Freedom to Give,” Inside Philanthropy (April 11)

- Jonathan Adler, “Justice Kavanaugh Stays District Court Order in Ohio Ballot Initiative Dispute,” The Volokh Conspiracy (April 11)

- “FIRE statement on immigration judge’s ruling that deportation of Mahmoud Khalil can proceed,” FIRE (April 11)

- Daryl Lim, “What would happen if Section 230 went away? Legal expert explains consequences of repealing ‘the law that built the internet’,” Free Speech Center (April 11)

- “The Mahmoud Khalil case is not about First Amendment rights, commentator says,” Fox News (April 11)

- Elena Barrera, “Appeals court upholds removal of Tallahassee police review board member over sticker,” Tallahassee Democrat (April 11)

- Ross Marchand, “UConn Med now lets students opt out of DEI pledge of allegiance,” FIRE (April 7)

2024-2025 SCOTUS term: Free expression and related cases

Cases decided

- Villarreal v. Alaniz (Petition granted. Judgment vacated and case remanded for further consideration in light of Gonzalez v. Trevino, 602 U. S. ___ (2024) (per curiam))

- Murphy v. Schmitt (“The petition for a writ of certiorari is granted. The judgment is vacated, and the case is remanded to the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit for further consideration in light of Gonzalez v. Trevino, 602 U. S. ___ (2024) (per curiam).”)

- TikTok Inc. and ByteDance Ltd v. Garland (9-0: The challenged provisions of the Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act do not violate petitioners’ First Amendment rights.)

Review granted

Pending petitions

Petitions denied

Emergency applications

- Yost v. Ohio Attorney General (Kavanaugh, J., “It Is Ordered that the March 14, 2025 order of the United States District Court for the Southern District of Ohio, case No. 2:24-cv-1401, is hereby stayed pending further order of the undersigned or of the Court. It is further ordered that a response to the application be filed on or before Wednesday, April 16, 2025, by 5 p.m. (EDT).”)

Free speech related

- Thompson v. United States (decided: 3-21-25/ 9-0 w special concurrences by Alito & Jackson) (interpretation of 18 U. S. C. §1014 re “false statements”)

Last scheduled FAN

FAN 465: “‘Executive Watch’: The breadth and depth of the Trump administration’s threat to the First Amendment”

This article is part of First Amendment News, an editorially independent publication edited by Ronald K. L. Collins and hosted by FIRE as part of our mission to educate the public about First Amendment issues. The opinions expressed are those of the article’s author(s) and may not reflect the opinions of FIRE or Mr. Collins.