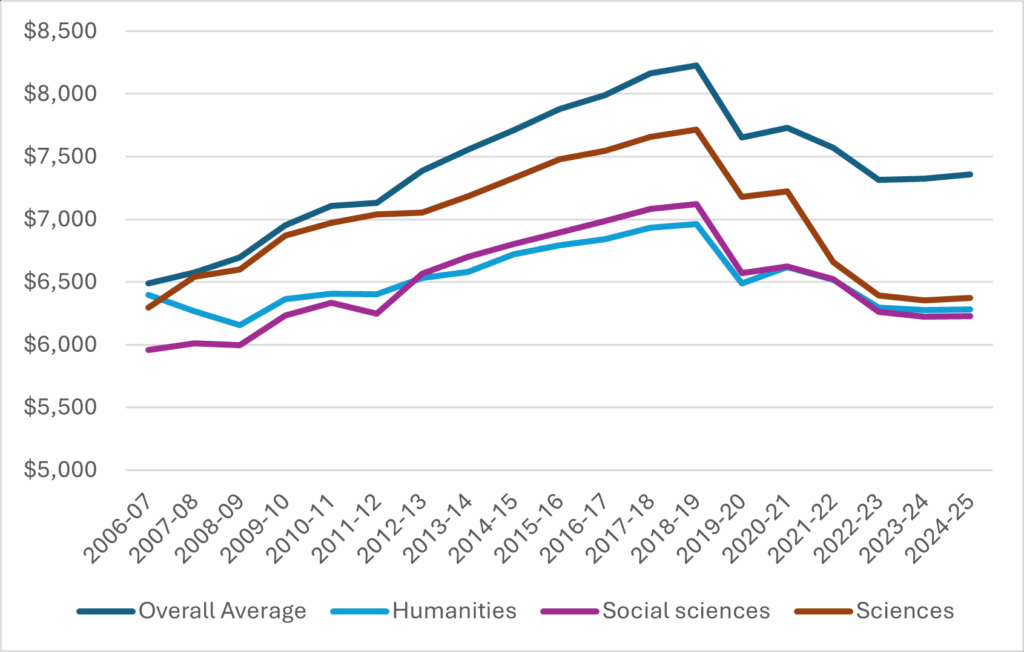

I want to show you something kind of intriguing about how tuition is changing in Canada.

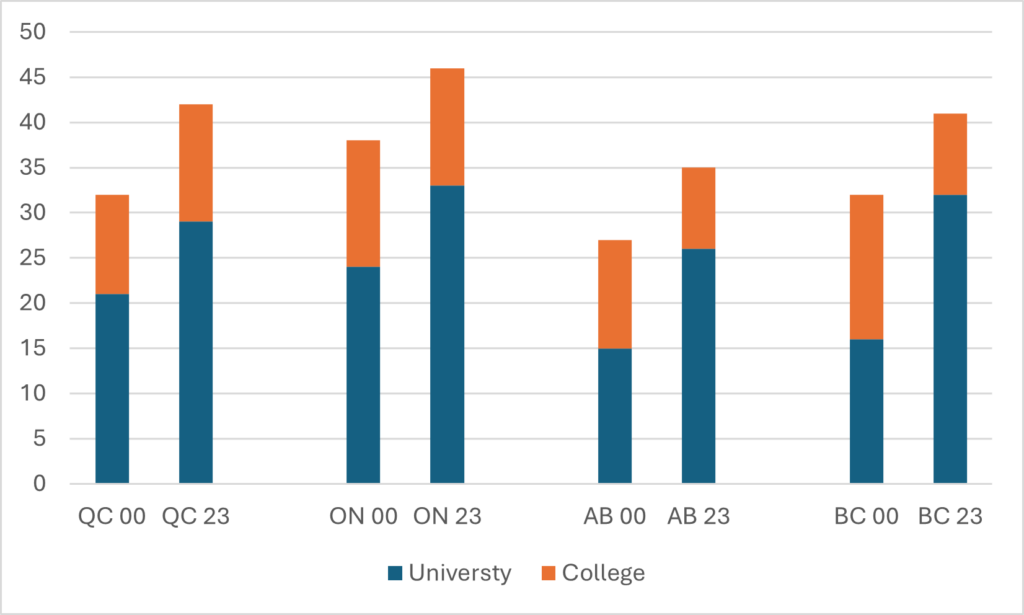

By now you might be familiar with a chart that looks like Figure 1, which shows average tuition, exclusive of ancillary fees (which would tack another $900-1000 on to the total), in constant $2024. The story it shows is one of persistent real increases from up until 2017-18, at which point, mainly thanks to policy changes in Ontario, tuition falls sharply and continues to fall as tuition increases across the country failed to keep up with inflation in the COVID years. Result: average tuition today, in real terms, is about where it was in 2012-13.

Figure 1: Average Undergraduate Tuition Fee, Canada, in $2024, 2006-07 to 2024-25

Simple story, right? Boring, even.

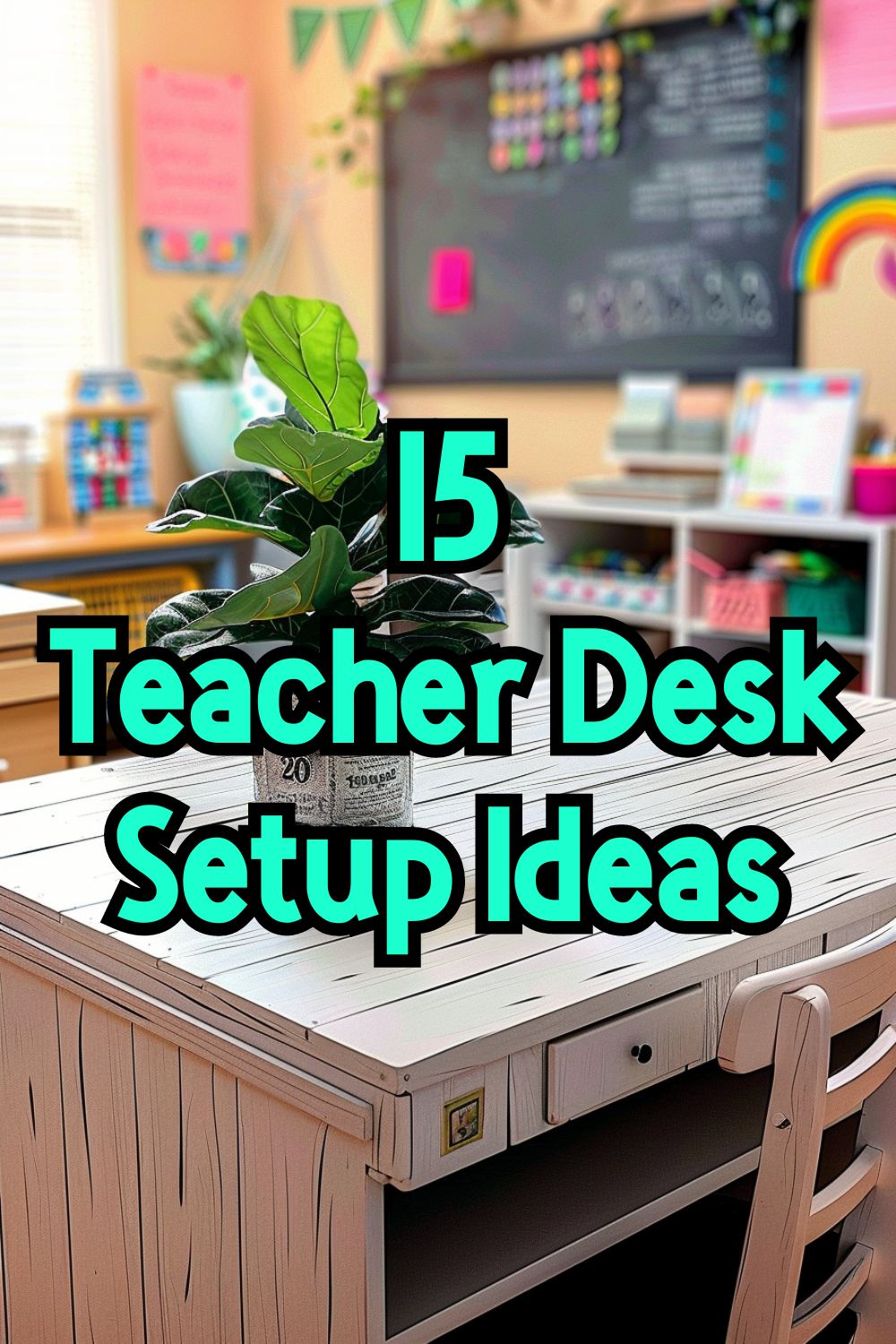

But then, just for fun, I decided to look at tuition at the level of individual fields of study. And what I found was kind of interesting. Take a look at Figure 2, which shows average tuition in what you might call the university’s three “core” areas: social science, humanities, and physical/life sciences. It’s quite a different story. The pre-2018 rise was never as pronounced as it was for tuition overall, and the drop in tuition post-2018 was more pronounced. As a result, tuition in the humanities is about even with where it was in 2006 and in the sciences is now three percent lower than it was in 2006.

Figure 2: Average Undergraduate Tuition Fee by Field of Study, Canada, in $2024, 2006-07 to 2024-25

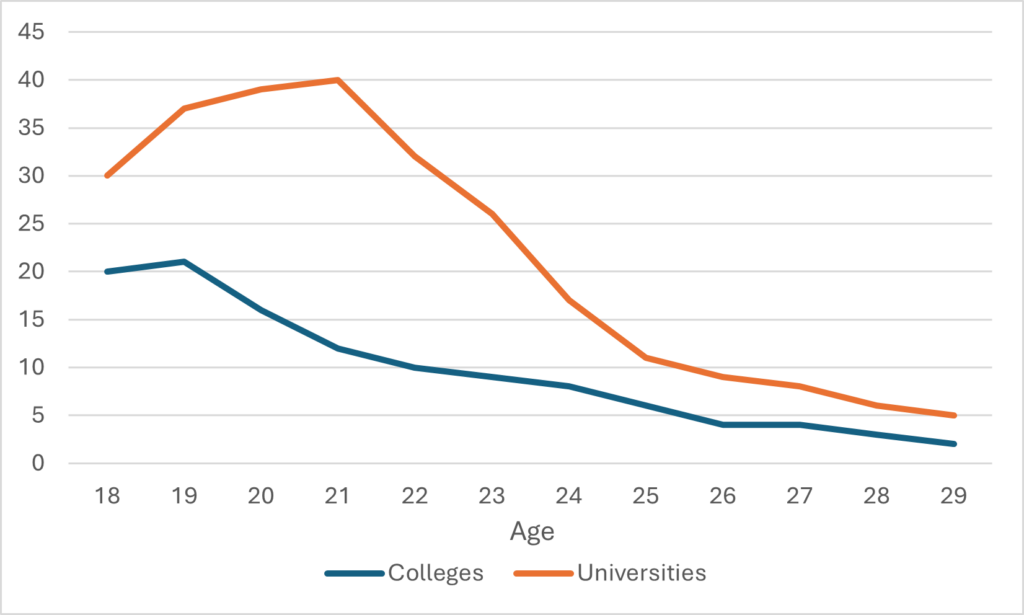

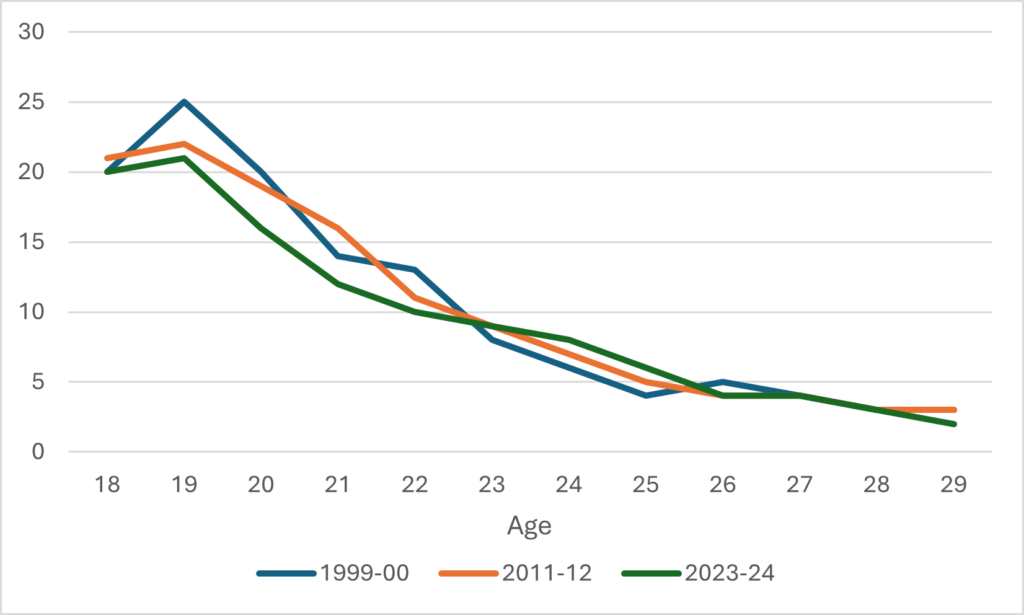

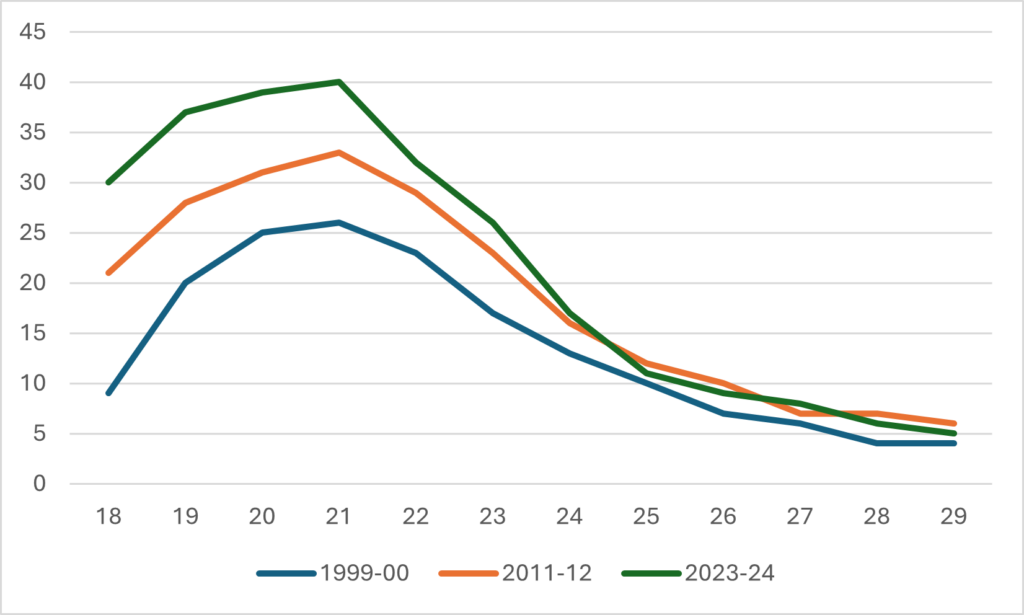

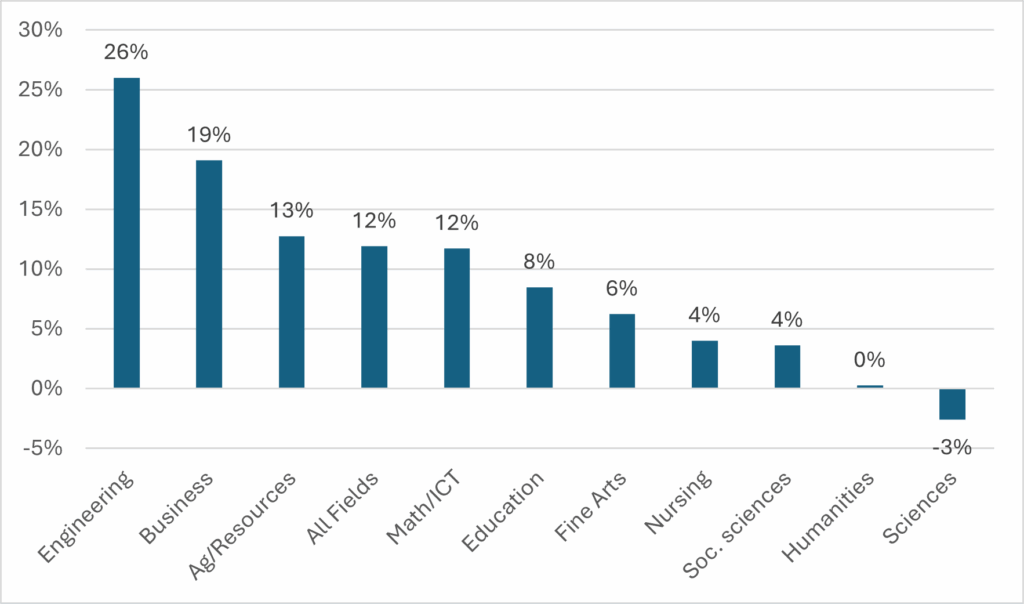

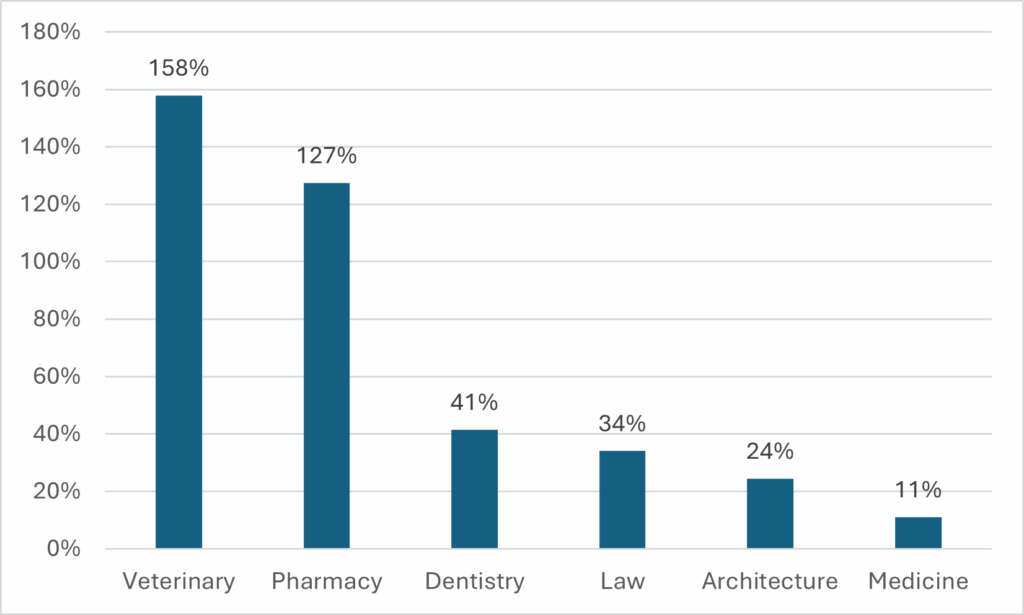

This got me thinking: how is it possible that the overall average tuition is rising so quickly when so many big disciplines are showing so little change? So I looked at the change in each discipline from 2006-07 to 2024-25. Figures 3 and 4 show the 18-year change in tuition for direct- and second-entry programs (and yes, this is an admittedly English Canadian distinction, since the programs in Figure 4 are also at least partially direct entry in Quebec).

Figure 3: Change in Real Tuition Levels, direct-entry undergraduate programs, Canada, 2006-07 to 2024-25

Figure 4: Change in Real Tuition Levels, second-entry undergraduate programs, Canada, 2006-07 to 2024-25

Two very different pictures, right? Quite clearly, second-entry degrees – which are a tiny fraction of overall enrolments – are nevertheless dragging the overall average up quite a bit. Unfortunately, it’s not easy to work out exactly how much because – inexplicably – Statscan does not use the same field of study boundaries for enrolment and tuition. But, near as I can figure out, there are about 15,000 students in law in Canada, 5,000 in pharmacy, 3,000 in dentistry and 2,000 in veterinary science. So that’s 25,000 students (or 2% of the undergraduate total) in fields with very high tuition increases, and a little back-of-the-envelope math suggests that these increases for just 2% of the student body were responsible for about 15% of all tuition growth.

Now, there is one other thing you have to look at and that is what is going on in engineering. This field has the fastest-growing real tuition over the period (26%) but is also the fastest-growing field in terms of domestic student enrolments (up 56% over the same period, compared to 16% for universities as a whole). So, compared with a world where engineering enrolments stayed steady between 2006-07 and 2024-25, an extra 22,000 people voluntarily enrolled in a field of study which was both more expensive (compared to science, average engineering tuition is about $2500 higher) and increasingly so every year. Again, a little back-of-the-envelope math shows that this phenomenon was responsible for between 10 and 11% of the growth in overall average tuition.

So, let’s add all that up: about a quarter of all the real growth in tuition over the past 20 years (which, as we noted at the outset wasn’t all that much to begin with) was due to tuition growth in the country’s most expensive programs. These are programs which are either growing rapidly or have long waiting lists, so I think the argument that these tuition increases have deterred enrolment is a bit far-fetched. And it means that the vast majority of students are seeing tuition fees which are well below the “average”. In fact, by my calculations, the actual increase in real dollars for that portion of the student body in first-degree programs – bar engineering – is somewhere around $625 in eighteen years.

Affordability crisis? Not really.