The Office for National Statistics (ONS) has published new estimates of suicides among higher education students, linking mortality records with student data between 2016 and 2023.

The findings are stark – 1,108 student deaths by suicide over seven years – an average of 160 each year, or more than three every week.

The headline takeaway, however, is that the suicide rate among students is lower than that of the general population of similar age. While technically correct, this framing is misleading and risks creating a false sense of reassurance.

The ONS emphasises that these are “statistics in development.” They are the product of recent advances in linking mortality and student record data, improving on older estimates. In that sense, this is important progress.

But the way the figures have been presented follows a familiar pattern: the headline is built around a simple comparison with the general population. It is neat, digestible, and apparently positive – yet it obscures more than it reveals.

This matters because the way numbers are framed shapes public understanding, institutional behaviour, and government response. If the story is “lower than average,” the implicit message is that the sector is performing relatively well. That is not the story these figures should be telling.

University students are not the “general population.” They are a distinct, filtered group. To reach higher education, young people must cross academic, financial, and often social thresholds. Many with the most acute or destabilising mental health challenges never make it to university, or leave when unwell.

The student body is also not demographically representative. Despite widening participation efforts, it remains disproportionately white and relatively affluent. Comparing suicide rates across groups with such different profiles is not comparing “like with like.”

In this context, a lower suicide rate is exactly what one would expect. The fact that the rate is not dramatically lower should be a cause for concern, not comfort.

It is easy to play with denominators. For example, students are in teaching and assessment for around 30 weeks of the year, not 52. If suicide risk were confined to term time, the weekly rate among students would exceed that of their peers.

But this recalculation is no better than the ONS comparison. Not all student deaths occur in term, and not all risks align neatly with the academic calendar.

You could take the logic further still. We already know there are peak moments in the academic cycle when deaths are disproportionately high – the start of the year, exam and assessment periods, and end-of-year transitions or progressions. If you recalculated suicide rates just for those concentrated stress points, the apparent risk would rise dramatically.

And that is the problem – once you start adjusting denominators in this way, you can make the statistics say almost anything. Both framings – “lower overall” and “higher in term” – shift attention away from the fundamental issue. Are students adequately protected in higher education?

Universities are not average society. They are meant to be semi-protected environments, with pastoral care, residential support, student services, and staff trained to spot risks. Institutions advertise themselves as supportive communities. Parents and students reasonably expect that studying at university will be safer than life outside it.

On that measure, the reality of more than three suicides a week is sobering. Whatever the relative rate, this is not “safe enough.”

Aggregate rates also obscure critical differences within the student body. The ONS data show that:

Headline averages conceal these inequalities. A “lower than average” message smooths over the very groups that most need targeted intervention.

Another striking feature is the absence of sector data. Universities do not systematically track student suicides. Instead, families must rely on official statisticians retrospectively linking death certificates with student records, often years later.

If the sector truly regarded these figures as reassuring, one might expect institutions to record and publish them. The reluctance to do so instead signals avoidance. Without routine monitoring, lessons cannot be learned in real time and accountability is diluted.

These challenges sit within a wider context – universities have no statutory duty of care towards their students. Families bereaved by suicide encounter unclear lines of accountability. Institutions operate on voluntary frameworks, policies, and codes of practice which are not always followed.

In that vacuum, numbers take on disproportionate weight. If statistics suggest the sector is “doing better than average,” the pressure for reform weakens. Yet the reality is that more than 1,100 students have died in seven years in what is supposed to be a protective environment.

Other countries offer a different perspective. In Australia, student wellbeing is embedded in national higher education policy frameworks. In the United States, campus suicide rates are monitored more systematically, and institutions are under clearer obligations to respond. The UK’s fragmented, voluntary approach looks increasingly out of step.

The new ONS dataset is valuable, but its framing risks repeating old mistakes. If we want real progress, three changes are needed:

The ONS release should not be read as reassurance. Both the official comparison with the general population and alternative recalculations that exaggerate term-time risk are statistical manipulations. They distract from the central point – 160 students a year, more than three every week, are dying by suicide in higher education.

Universities are meant to be safer than average society. The reality shows otherwise. Until higher education is bound by a legal duty of care and institutions commit to transparency and accountability, statistical debates will continue to obscure systemic failures – while friends and families will continue to bear the consequences.

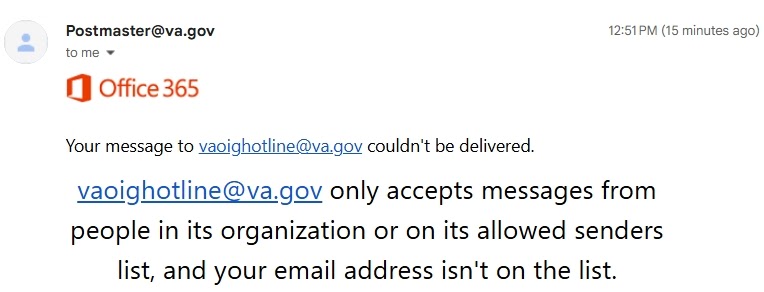

The Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Inspector General (VA OIG), is no longer accepting tips from veterans who have been ripped off by predatory subprime colleges–at least not via email. The Higher Education Inquirer, at one time, was an important source for information for the VA OIG, but the VA’s watchdogs stopped corresponding with us a few years ago for no apparent reason. This failure to communicate is part of a longstanding pattern of indifference by the US Government (VA, DOD, ED, and DOL) and veterans’ organizations towards military servicemembers, veterans, and their families who are working to improve their job skills and job prospects.

VA’s chatbot also has much to be desired.

BALTIMORE — When educators operate with separate goals and don’t engage in authentic collaboration, it creates friction and can ultimately hurt student progress, said Casey Watts, an educator and team leadership expert, in the opening keynote address at the Council for Exceptional Children’s annual convention on Wednesday.

“I believe that people deserve to be part of collaborative teams that move forward, make an impact together and leave them feeling empowered, inspired and essential,” said Watts, who is also a pre-K-5 instructional coach at Hudson Independent School District in Lufkin, Texas.

When educators and administrators are siloed, there can be an “us versus them” mentality, she said. “I believe that when we function in silos as educators, we unintentionally create silos in our students.”

To dismantle barriers between general and special educators and between teachers and administrators, Watts recommends three core concepts:

Maintaining a strong sense of identity and purpose in your work can help eliminate ambiguities and assumptions others have of your role at school, Casey said. This goes for all educators in the school, including special education teachers, general education teachers, counselors, administrators and others.

To ensure clarity, educators should work on their “elevator pitch,” or a brief summary of their role in the school. “When you create an elevator pitch, what you are essentially doing is pulling people in to become the main character of the story, and you are addressing their pain points, and you’re giving them new narratives for your position, which in essence, is bridging the gaps that exist between us as adults in education,” Watts said.

In developing their elevator pitches, educators should think about how their role serves others in the school building and the skills they offer to educators and students.

Authentic collaboration is easier said than done, Watts said. And some “faux collaborations” can seem promising — such as an offer to share resources and materials — but really don’t break down barriers among educators.

True collaboration takes courage and vulnerability and can include difficult conversations. It also means using everyone’s strengths and listening to all voices, she said.

Establishing protocols where each person in the school community is a contributor can help break down silos, Watts said.

When everyone is on the same path, they know where the team is headed and how to get there. But when goals are unclear or the path is uncertain, people can get off track or operate independently, Watts said.

When that happens, teachers go into their classrooms, close the door and vow to do what’s best for their students. But that can lead to unintentional gaps in student learning.

“As I work with teams in districts across the nation, I hear so often leaders say ‘our teachers just won’t get on board,’” Watts said. “On the flip side of that, I’m hearing from teachers and staff who are saying the opposite: ‘We just never know what’s going on.’ There are two different narratives at play.”

A lack of clarity creates unproductive confusion, Watts said. As a result, educators and administrators might lack confidence and feel defeated, frustrated and distrustful, she said.

Setting out clear goals will boost confidence and capacity in educators, resulting in a collective efficacy, Watts said. That, in turn, will have “a significant impact on student learning,” she said.

by CUPA-HR | March 27, 2023

On March 22, National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) General Counsel Jennifer Abruzzo issued a memo to all field offices with guidance on the Board’s recent decision in McLaren Macomb, in which the Board decided that employers cannot offer employees severance agreements that require employees to waive rights under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), such as confidentiality and non-disparagement requirements. According to the NLRB’s press release, the memo is to be used as guidance to assist field offices responding to inquiries from workers, employers, labor unions and the public about implications stemming from McLaren Macomb.

The memo offers guidance on the decision’s scope and effect of the McLaren Macomb decision. In the memo, Abruzzo stated that the decision has retroactive application, and she directed employers who may have previously offered severance agreements with “overly broad” non-disparagement or confidentiality provisions to contact employees to advise them that such provisions are now void and will not be enforced. Abruzzo also clarified that confidentiality clauses that are “narrowly tailored” to restricting dissemination of proprietary information or trade secrets may still be lawful “based on legitimate business justifications,” and that non-disparagement clauses that are limited to “employee statements about the employer that meet the definition of defamation as being maliciously untrue (…) may be found lawful.”

With respect to supervisors, Abruzzo specified that supervisors are not generally protected by the NLRA, but she added that they are protected from retaliation if they refuse to offer a severance agreement with broad non-disparagement or confidentiality provisions to their employees.

As a reminder, CUPA-HR will be hosting a webinar on the McLaren Macomb decision Thursday, March 30 at 1:00 p.m. ET. The webinar will cover the McLaren Macomb decision and this subsequent memo, and presenters will discuss how the decision may fundamentally change how and when colleges and universities may use confidentiality and non-disparagement provisions. Registration is required for participation, but free to all CUPA-HR members.

by CUPA-HR | September 29, 2021

On September 29, National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) General Counsel Jennifer Abruzzo released a memorandum stating her position that student athletes (or “Players at Academic Institutions,” as she refers to them in the memo) are employees under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) and are afforded all statutory protections as prescribed under the law. Abruzzo declares, “The broad language of Section 2(3) of the [NLRA], the policies underlying the NLRA, Board law, and the common law fully support the conclusion that certain Players at Academic Institutions are statutory employees, who have the right to act collectively to improve their terms and conditions of employment.”

Abruzzo also states that misclassifying such individuals as non-employees and leading them to believe they are not afforded protections under the NLRA has a “chilling effect” on Section 7 activity. She said she would consider this misclassification an independent violation of Section 8(a)(1) of the NLRA. Abruzzo further stated that the intent of the memo is to “educate the public, especially Players at Academic Institutions, colleges and universities, athletic conferences, and the NCAA” about her position in future appropriate cases.

The memo revives issues surrounding employment status of student athletes that the NLRB has previously ruled on. In March 2014, the NLRB’s Regional Director in Chicago ruled that Northwestern players receiving football scholarships are employees and have a right to organize under the NLRA. In August 2015, the NLRB released a unanimous decision dismissing the representation petition filed by a group of Northwestern football players seeking to unionize. In doing so, however, the board’s decision did not definitively resolve the issue of whether college athletes are employees and have a protected right to unionize under the NLRA. After considering arguments of both parties in the case and various amici, including CUPA-HR, the board declined to assert jurisdiction on the issue, stating that “asserting jurisdiction would not promote labor stability [because the] Board does not have jurisdiction over state-run colleges and universities, which constitute” the vast majority of the teams. The board noted, however, its “decision is narrowly focused to apply only to the players in this case and does not preclude reconsideration of this issue in the future.” Another issue in the Northwestern decision was the board’s lack of jurisdiction over “walk-on” players who do not receive scholarships. It remains to be seen how Abruzzo will overcome in future cases the two jurisdictional obstacles identified in Northwestern.

CUPA-HR will keep members apprised of NLRB actions and cases that may prompt the agency to rule on the issue regarding student athlete employment status.