Search behaviour among prospective students is evolving fast. Instead of scrolling through pages of search results, many now turn to AI-powered tools for instant, conversational answers. This shift has introduced a new layer to traditional SEO: Generative Engine Optimization (GEO).

GEO focuses on optimizing content so that generative AI search engines like ChatGPT or Google’s AI Overview can find, interpret, and feature it in their responses. In essence, GEO ensures your institution’s information is selected, summarized, or referenced in AI-generated answers, rather than simply ranking in a list of links.

Higher education marketers in Canada and beyond must pay attention to this trend. Recent global studies indicate that nearly two-thirds of prospective students use AI tools such as ChatGPT at some stage of their research process, with usage highest during early discovery and comparison phases.

These tools pull content from across the web and present synthesized answers, often eliminating the need for users to click. This “zero-click” trend reduces opportunities for organic traffic, raising the stakes for visibility within AI systems.

This guide explores GEO’s role in education marketing, how it differs from traditional SEO, and why it matters for student recruitment in the age of AI. You’ll find practical guidance on aligning your content with generative AI, from keyword strategy to page prioritization. We’ll also look at how to measure GEO’s impact on inquiries and enrolment, and share examples from institutions leading the way.

What Is Generative Engine Optimization (GEO) in Higher Education Marketing?

Generative Engine Optimization (GEO) is the practice of tailoring university content for AI-driven search tools like ChatGPT and Google’s AI Overview. Unlike traditional SEO, which targets search engine rankings, GEO focuses on making content readable, reliable, and retrievable by generative AI.

In higher ed, this means structuring key program details, admissions information, and differentiators so that AI tools can easily surface and cite them in responses. GEO builds on classic SEO principles but adapts them for a zero-click, conversational environment, ensuring your institution appears in AI-generated answers to prospective student queries.

How Is GEO Different from Traditional SEO for Universities and Colleges?

While both SEO and GEO aim to make your institution’s content visible, their approaches diverge in method and target. Traditional SEO is designed for search engine rankings. GEO, on the other hand, prepares content for selection and citation by AI tools that deliver instant answers rather than search results.

Let’s break it down.

Search Results vs. AI Answers

SEO optimizes for clicks on a search results page. GEO optimizes for inclusion in a conversational answer. Instead of showing up as a blue link, your institution may be quoted or named by the AI itself.

Keyword Strategy

SEO prioritizes high-volume keywords. GEO relies on semantic relevance. Instead of “MBA program Canada,” think “How long is the MBA at [University]?” or “What are the admission requirements?”

Content Structure

Traditional SEO values user navigation. GEO values clarity for AI parsing. Bullet points, Q&A formatting, and schema markup make it easier for AI to extract information. Summary boxes and tables work better than long paragraphs.

Authority Signals

E-E-A-T (Experience, Expertise, Authoritativeness, Trustworthiness) still matters. But for GEO, authority is inferred from citation style, accuracy, and consistency, not design or branding. Highlighting faculty credentials or linking to research enhances AI credibility scoring.

Technical Approach

Both SEO and GEO require clean, crawlable websites. But GEO adds machine-readable formatting. Schema.org markups, downloadable data files, and clean internal linking increase your chances of being selected by AI.

Measuring Success

SEO measures traffic, rankings, and form fills. GEO measures citations in AI responses, brand mentions, and voice assistant visibility. You might not get the click, but you still win visibility if the AI says your name.

In practice, this means layering GEO on top of existing SEO. A strong program page might combine narrative storytelling with a quick facts section. An admissions page should include both persuasive copy and an FAQ schema.

Bottom line: SEO helps you get found. GEO helps you get cited. And in the age of AI, both are essential to capturing attention at every stage of the student search journey.

Why GEO Matters for Student Recruitment in the Age of AI Search

Why is GEO important for student recruitment in the age of AI search? Generative AI search is already reshaping how prospective students discover, evaluate, and select postsecondary institutions. GEO (Generative Engine Optimization) equips institutions to remain visible and competitive in this changing environment. Here’s why it matters now more than ever:

- Widespread Adoption by Gen Z

Today’s students are early adopters of generative AI. A 2024 global survey found that approximately 70% of prospective students have used AI tools like ChatGPT to search for information, and more than 60% report using chatbots during the early phases of their college research. This shift means fewer students are navigating university websites as a first step.

Instead, they’re posing detailed questions to AI, questions about programs, financial aid, campus life, and more. GEO ensures your institution’s information is accessible, machine-readable, and accurate in this discovery environment. Without it, you risk being excluded from the initial consideration set.

- The Rise of Zero-Click Search Behavior

AI-generated responses often satisfy a query without requiring a website visit. This zero-click trend is accelerating, as nearly 60% of searches now end without a click. If a student asks, “What are the top universities in Canada for engineering?” and an AI tool responds with a synthesized answer that names three schools, those schools have won visibility without needing a traditional click-through.

GEO is your institution’s strategy for occupying that limited space in the answer. It’s how you shape perceptions in a search landscape where attention is won before a student reaches your homepage.

- AI Is Becoming a College Advisor

Though current data shows AI has limited direct influence on final enrollment decisions, that influence is growing. As AI tools become more trusted, students will increasingly rely on them for shortlisting programs or comparing institutions. GEO ensures your content is part of those suggestions and comparisons.

For example, a prospective student might ask, “Which is better for computer science, [Competitor] or [Your University]?” Without well-structured, AI-optimized content, your institution may be left out or misrepresented. GEO levels the playing field, ensuring that when AI generates side-by-side evaluations, your offerings are accurate, current, and competitive.

- Fewer Chances to Impress

Traditional SEO offered multiple entry points: page one, page two, featured snippets, and ads. AI-generated answers are far more concise, often limited to a single paragraph or a brief list of citations. That means your institution must compete for a narrower spotlight.

GEO increases your odds of selection by helping AI tools find and cite the most relevant, structured, and authoritative content. When students ask about tuition, deadlines, or international scholarships, you want the answer to come from your website, not a third-party aggregator or a competing institution.

- Boosting Brand Trust and Authority

Being cited in AI responses lends credibility. Much like appearing at the top of Google results used to signal trustworthiness, consistent AI mentions confer authority. If ChatGPT, Google SGE, or Bing AI repeatedly reference your institution in educational queries, students begin to perceive your brand as reliable.

This builds long-term recognition, resulting in some students visiting your site simply because they’ve encountered your name often in AI responses. GEO helps position your institution as a trusted source across AI-driven search platforms, reinforcing brand equity and enhancing recruitment outcomes.

In Summary

GEO is rapidly becoming a critical component of modern higher education student recruitment marketing strategies. It ensures your institution is visible in the conversational, AI-driven search experiences that are now shaping student decisions. Just as universities once adjusted to mobile-first web browsing, they must now adapt to AI-first discovery.

GEO helps your institution appear in AI answers, influence prospective students early in their journey, and remain top of mind even when clicks don’t happen. For institutions navigating declining enrollments and intensifying competition, GEO is a forward-facing strategy that keeps you in the conversation and in the race for the next generation of learners.

How Can a University Website Be Optimized for AI Tools like ChatGPT and Google AI Overviews?

Optimizing a university website for generative AI search requires a blend of updated content strategy, technical precision, and practical SEO thinking. The goal is to ensure your institution’s content is not only findable but also understandable and usable by AI models such as ChatGPT or Google’s AI Overviews. Here are two key strategies to implement:

1. Embrace a Question-First Content Strategy Using GEO Keywords

Begin by identifying the natural-language queries prospective students are likely to ask. Instead of traditional keyword stuffing, build your content around direct, conversational questions with what we call “geo keywords.” For example: “What is the tuition for [University]’s nursing program?” “Does [University] require standardized tests?”, or “What scholarships are available for international students?”

Structure content using Q&A formats, headings, and short paragraphs. Include these questions and their answers prominently on program, admissions, or financial aid pages. FAQ sections are particularly effective since AI tools are trained on question-based formats and favor content with semantic clarity.

Audit your current site to uncover missing or buried answers. Use data from tools like Google Search Console or internal search analytics to surface frequent queries. Then, present responses in clear formats that both users and AI systems can digest.

2. Create Clear, Canonical Fact Pages for Key Information

AI tools rely on consistency. If your website offers multiple versions of key facts, such as tuition, deadlines, or admission requirements, AI may dismiss your content entirely. To avoid this, create canonical pages that serve as the single source of truth for essential topics.

For example, maintain a central “Admissions Deadlines” page with clearly formatted lists or tables for each intake period. Similarly, your “Tuition and Fees” page should break down costs by program, year, and student type.

Avoid duplicating this information across many pages in slightly different wording. Instead, link other content back to these canonical pages to reinforce credibility and reduce confusion for both users and AI. By prioritizing clarity, structure, and authority, your website becomes significantly more AI-compatible.

3. Structure Your Content for AI (and Human) Readability

Generative AI reads websites the way humans skim for quick answers, only faster and more literal. For your institution to show up in AI-generated results, your site must be structured clearly and logically. Here are six modern content strategies that improve readability for both users and machines:

1. Put Important Information Up Front

AI tools often extract the first one or two sentences from a page when forming answers. Lead with essential facts: program type, duration, location, or unique rankings. For example:

A four-year BSc Nursing program ranked top 5 in Canada for clinical placements.

Avoid burying key points deep in your content. Assume the AI won’t read past the opening paragraph, and prioritize clarity early.

2. Use Headings, Lists, and Tables

Break up long content blocks using headings (H2s and H3s), bullet points, and numbered lists. These structures improve scanning and help AI identify and categorize information correctly.

Instead of a paragraph on how to apply, write:

How to Apply:

- Submit your online application

- Pay the $100 application fee

- Upload transcripts and supporting documents

For data or comparisons, use simple tables. A table of admissions stats or tuition breakdowns is easier for AI to interpret than buried prose.

3. Standardize Terminology Across Your Site

Inconsistent language can confuse both users and AI. Choose one label for each concept and use it site-wide. For example, if your deadline page says “Application Deadline,” don’t refer to it elsewhere as “Closing Date” or “Due Date.”

Uniform terminology supports clearer AI parsing and reinforces credibility.

4. Implement Schema Markup

Schema markup is structured metadata added to your HTML that explicitly communicates the purpose of your content. It is critical to make content machine-readable.

Use JSON-LD and schema types like:

- FAQPage for question-answer sections

- EducationalOccupationalProgram for program details

- Organization for your institution’s info

- Event for admissions deadlines or open houses

Google and other AI systems rely heavily on this data. Schema also helps with traditional SEO by enabling rich snippets in search results.

5. Offer Machine-Readable Data Files

Forward-looking universities are experimenting with downloadable data files (JSON, CSV) that list key facts, such as program offerings or tuition. These can be made available through a hidden “data hub” on your site.

AI systems may ingest this structured content directly, improving the likelihood of accurate citations. For example, the University of Florida’s digital team reported that their structured content significantly improved the accuracy of Google AI Overviews summarizing their programs.

4. Keep Content Fresh and Consistent Across Platforms

AI tools favor accurate and current information. Outdated or conflicting content can lead to mistrust or exclusion. Best practices include:

- Timestamping pages with “Last updated [Month, Year]”

- Conducting regular audits to eliminate conflicting data

- Using canonical tags to point AI toward the primary source when duplicate content is necessary

- Aligning off-site sources like Wikipedia or school directory listings with your website’s data

For instance, if your homepage says 40,000 students and Wikipedia says 38,000, the AI may average the two or cite the incorrect one. Keep external sources accurate and consistent with your site.

5. Optimize for Specific AI Platforms (ChatGPT, Google SGE, etc.)

Each AI platform has different behaviors. Here is how to tailor your content for them:

ChatGPT (OpenAI)

Free ChatGPT may not browse the web, but ChatGPT Enterprise and Bing Chat do. These versions often rely on training data that includes popular and high-authority content.

To increase visibility:

- Publish long-form, high-quality content that gets cited by others

- Use backlink strategies to improve domain authority

- Create blog posts or guides that answer common student questions clearly

Even if your content isn’t accessed in real time, if it has been crawled or cited enough, it may be paraphrased or referenced in AI answers.

Google AI Overview (formerly SGE)

Google’s AI Overviews (formerly Search Generative Experience, or SGE draws from top-ranking search results. So, traditional SEO performance directly influences GEO success.

Best practices include:

- Use concise, answer-oriented snippets early in content (e.g., “General admissions require a 75% average and two references.”)

- Ensure pages are crawlable and not blocked by scripts or logins

- Reinforce AI clarity with schema and consistent internal linking

Voice Assistants (Siri, Alexa, Google Assistant)

These tools favor featured snippets and structured content. A direct response like: “Yes, we offer a co-op program as part of our Bachelor of Computer Science” is more likely to be read aloud than a paragraph with buried details.

Emerging Tools (Perplexity.ai, Bing Chat)

These newer AI search tools cite sources like Wikipedia and high-authority sites. To prepare:

- Keep your institution’s Wikipedia page accurate and updated

- Monitor and correct public conversations (e.g., Reddit, Quora) with official clarifications on your website

- Consider publishing myth-busting content to preempt misinformation

Structuring your content for AI doesn’t mean abandoning human readers. In fact, the best practices that help machines, clarity, structure, and accuracy, also create better experiences for prospective students. By aligning your strategy with the expectations of both audiences, your university remains visible, credible, and competitive in the evolving search landscape.

6. Leverage Institutional Authority and Unique Content

Your organization holds content assets that AI deems both authoritative and distinctive, be sure to leverage them strategically. Showcase faculty research, student success outcomes, and institutional data on your site in clear, extractable formats. For instance:

“Over 95% of our graduates secure employment within six months (2024 survey).”

Include program differentiators, accolades, and unique offerings that set your institution apart. AI-generated comparisons often cite such features. Strengthen content credibility with E-E-A-T principles:

- Add author bylines and bios to expert-led blog posts

- Cite trusted third-party sources and rankings

- Present information factually while still engaging human readers

For example, pair promotional language (“modern dorms”) with direct answers (“First-year students are required to live on campus”). This dual-purpose approach ensures your content feeds both AI responses and prospective student curiosity.

In short, AI rewards clear, credible, question-first content. Make sure yours leads the conversation.

Which Higher Education Pages Should Be Prioritized for GEO?

Not all web pages carry equal weight when it comes to generative engine optimization (GEO). To improve visibility in AI-generated search responses, universities should prioritize content that addresses high-intent queries and critical decision-making touchpoints.

- Academic Program Pages

These are foundational. When users ask, “Does [University] offer a data science degree?”, AI tools pull from program pages. Each page should clearly outline program type, duration, delivery mode, concentrations, accreditations, rankings, and outcomes. Include key facts in the opening paragraph and use structured Q&A to address specifics like “Is co-op required?” or “Can I study part-time?” - Admissions Pages

AI queries often focus on application requirements. Structure admissions pages by applicant type and use clear subheadings and bullet points to list requirements, deadlines, and steps. Include canonical deadline pages with visible timestamps, and FAQ-style answers such as “What GPA is required for [University]?” - Tuition, Scholarships, and Financial Aid

Cost-related questions are among the most common. Ensure tuition and fee data are presented in clear tables, by program and student type. Scholarship and aid pages should state eligibility, values, and how to apply in plain language, e.g., “All applicants are automatically considered for entrance scholarships up to $5,000.” - Program Finders and Academic Overview Pages

Ensure your program catalog and A–Z listings are crawlable, up-to-date, and use official program names. Pages summarizing academic strengths should highlight standout offerings: “Our business school is triple-accredited and ranked top 5 in Canada.” - Student Life and Support Services

AI often fields questions like “Is housing guaranteed?” or “What mental health resources are available?” Answer these directly: “All first-year students are guaranteed on-campus housing.” Showcase specific services for key demographics (e.g., international students, veterans) with quantifiable benefits. - Career Outcomes and Alumni Success

Publish recent stats and highlight notable alumni. Statements like “93% of our grads are employed within 6 months” or “Alumni have gone on to roles at Google and Shopify” provide AI with strong content to surface in answers.

How Can Institutions Measure the Impact of GEO on Inquiries and Enrolment?

Measuring the impact of Generative Engine Optimization (GEO) requires a mix of analytics, qualitative monitoring, and attribution strategies. Since GEO outcomes don’t always show up in traditional SEO metrics, institutions must adopt creative, AI-aware approaches to track effectiveness.

- Monitor AI Referral Traffic

Check Google Analytics 4 (GA4) or similar platforms for referral traffic from AI tools like Bing Chat or Google SGE. While not all AI sources report referrals, look for domains like bard.google.com or bing.com and configure dashboards to track them. Even small traffic volumes from these sources can indicate growing visibility. - Track AI Mentions and Citations

Manually query AI tools using prompts like “Tell me about [University]” or “How do I apply to [University]?” and log whether your institution is cited. Note if AIs reference your site, Wikipedia, or other sources. Track frequency and improvements over time, especially following content updates. Screenshots and logs can serve as powerful internal evidence. - Use Multi-Touch Attribution

Students may not click AI links, but still recall your brand. Add “How did you hear about us?” options in inquiry forms, including “ChatGPT” or “AI chatbot.” Monitor brand search volume and direct traffic following GEO updates. Qualitative survey insights and CRM notes from admissions teams can help reveal hidden AI touchpoints. - Analyze GEO-Optimized Page Engagement

Watch how the pages you optimize for GEO perform. Increased pageviews, lower bounce rates, and higher conversion (e.g., info form fills) may indicate better alignment with AI outputs and human queries alike, even if AI is only part of the traffic source. - Observe Funnel Shifts and Segment Trends

Notice any spikes in inquiries for certain programs or demographics that align with AI visibility. For example, a rise in international applications after enhanced program content could suggest AI exposure. - Build a GEO Dashboard

Create simple internal dashboards showing AI referrals, engagement trends, citation screenshots, and timelines of GEO initiatives. Correlate those with enrollment movement when possible. - Test, Refine, Repeat

Experiment continuously. A/B test content formats, restructure FAQs, and see which phrasing AI picks up. Treat AI outputs as your new SEO testbed.

While GEO analytics are still evolving, early movers gain visibility and mindshare. Measuring what’s possible now ensures institutions are positioned to lead as AI search reshapes student discovery.

10 Global Examples of GEO in Practice (Higher Ed Institutions)

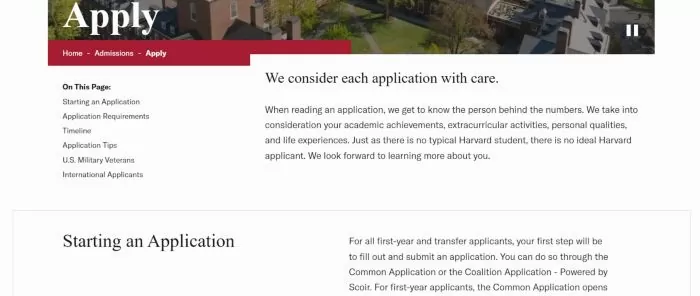

1. Harvard University: Harvard College Admissions “Apply” Page

Harvard’s undergraduate admissions Apply page (Harvard College) is a model of clear, structured content. The page is organized with intuitive section headings (e.g., Application Requirements, Timeline) and even an on-page table of contents for easy navigation.

It provides a bullet-point list of all required application components (from forms and fees to test scores and recommendations), ensuring that key information is presented succinctly.

Source: Harvard University

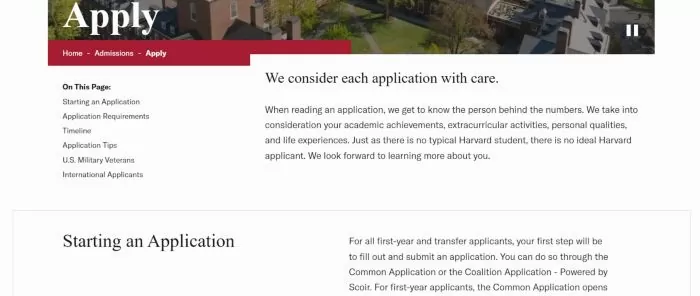

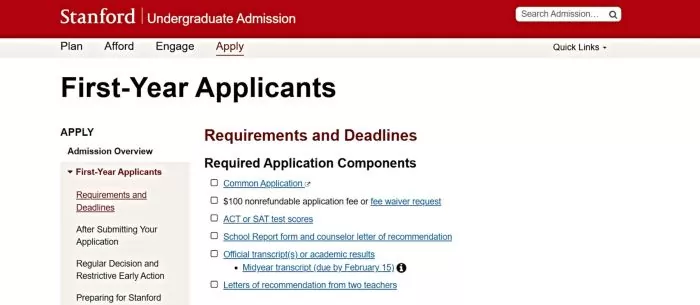

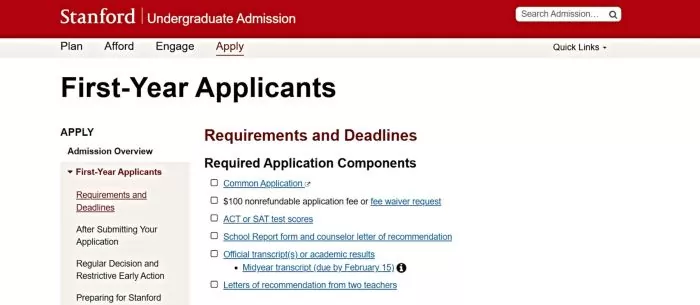

2. Stanford University: First-Year Applicants “Requirements and Deadlines” Page

Stanford’s first-year admission page stands out for its semantic, structured presentation of information. It opens with a clearly labeled checklist of Required Application Components, presented as bullet points (e.g., Common Application, application fee, test scores, transcripts, etc.). Following this, Stanford provides a well-organized Requirements and Deadlines table that outlines key dates for Restrictive Early Action and Regular Decision side by side.

In this table, each milestone, from application submission deadlines (e.g., November 1 for early, January 5 for regular) to notification dates and reply deadlines, is neatly aligned, which is both user-friendly and easy for AI to parse.

Source: Stanford University

3. Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT): “About MIT: Basic Facts” Page

MIT Admissions offers an About MIT: Basic Facts page that is essentially a treasure trove of quick facts and figures presented in bullet form. This page exemplifies GEO best practices by curating the institute’s key data points (e.g., campus size, number of students, faculty count, notable honors) as concise bullet lists under intuitive subheadings.

For instance, the page lists campus details like acreage and facilities, student demographics, and academic offerings in an extremely scannable format. Each bullet is a self-contained fact (such as “Undergraduates: 4,576” or “Campus: 168 acres in Cambridge, MA”), making it ideal for AI summarization or direct answers. Because the content is broken down into digestible nuggets, an AI-powered search can easily extract specific information (like *“How many undergraduate students does MIT have?”) from this page.

Source: MIT

4. University of Toronto: Undergraduate “Dates & Deadlines” Page

The University of Toronto’s Dates & Deadlines page for future undergraduates is a great example of structured scheduling information. It presents application deadlines in a highly structured list, broken down by program/faculty and campus. The page is organized into expandable sections (for full-time, part-time, and non-degree studies), each containing tables of deadlines.

For example, under full-time undergraduate applications, the table clearly lists each faculty or campus (Engineering, Arts & Science – St. George, U of T Mississauga, U of T Scarborough, etc.) alongside two key dates: the recommended early application date and the final deadline. This means a prospective student can quickly find, say, the deadline for Engineering (January 15) and see that applying by November 7 is recommended.

Such a format is not only user-friendly but also easy for AI to interpret. The consistency and labeling (e.g., “Applied Science & Engineering, November 7 (recommended) / January 15 (deadline)”) ensure that an AI answer to “What’s the application deadline for U of T Engineering?” will be accurate.

Source: University of Toronto

5. University of Oxford: English Language and Literature Course Page

Oxford’s course page for English Language and Literature showcases GEO-friendly content right at the top with a concise Overview box. This section acts as a quick-reference summary of the course, listing crucial facts in a compact form. It includes the UCAS course code (Q300), the entrance requirements (AAA at A-level), and the course duration (3 years, BA) clearly on separate lines. Immediately below, it outlines subject requirements (e.g., Required: English Literature or English Lang/Lit) and other admission details like whether there’s an admissions test or written work, all in the same straightforward list format.

This means a prospective student (or an AI summarizing Oxford’s offerings) can get all the key info about the English course at a glance – from how long it lasts to what grades are needed.

Source: Oxford University

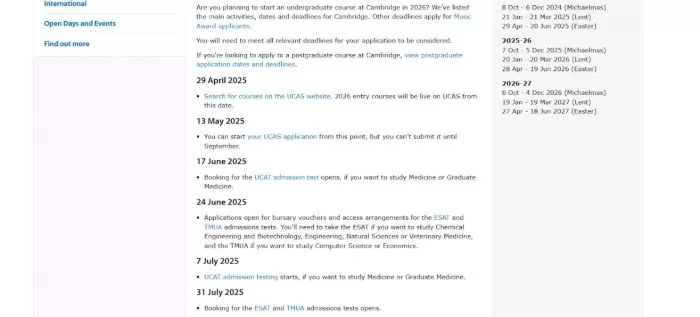

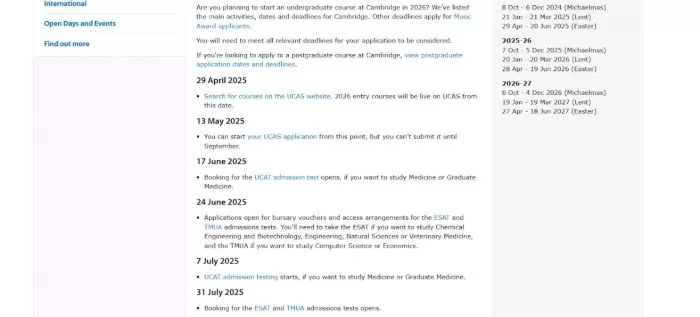

6. University of Cambridge: Application Dates and Deadlines Page

Cambridge’s admissions website provides a dedicated Application Dates and Deadlines page that reads like a detailed timeline of the entire admissions process. This page lays out, in chronological order, all the key steps and dates for applying to Cambridge, with each date accompanied by a short explanation of what happens or what is due.

For example, it starts as early as the spring of the year before entry, noting when UCAS course search opens and when you can begin your UCAS application. Critically, it flags the famous 15 October UCAS deadline with emphasis: “15 October 2025 – Deadline to submit your UCAS application (6 pm UK time)”. Other entries include deadlines for supplemental forms like the My Cambridge Application (22 October), dates for admissions tests, and notes about interview invitations in November and December.

Source: University of Cambridge

Staying Discoverable in the Age of Generative Search

Generative Engine Optimization (GEO) is rapidly shifting from trend to necessity in higher education marketing. As AI-driven platforms like ChatGPT, Google SGE, and voice assistants reshape how students seek information, institutions must adapt their content strategies accordingly.

By aligning with modern GEO practices, universities enhance both discoverability and user experience, meeting students where they are and ensuring their narratives are accurately represented. In today’s competitive enrolment landscape, GEO is not optional; it is foundational. The strategies outlined above provide a roadmap for sustainable visibility in the age of generative search. Continue refining your approach, and your institution will not just appear in AI responses; it will lead them. In this new era, the goal is simple: be cited, not sidelined.

FAQs

Q: What is generative engine optimization (GEO) in higher education marketing?

A: Generative Engine Optimization (GEO) is the practice of tailoring university content for AI-driven search tools like ChatGPT and Google’s AI Overview. Unlike traditional SEO, which targets search engine rankings, GEO focuses on making content readable, reliable, and retrievable by generative AI.

Q: How is GEO different from traditional SEO for universities and colleges?

A: While both SEO and GEO aim to make your institution’s content visible, their approaches diverge in method and target. Traditional SEO is designed for search engine rankings. GEO, on the other hand, prepares content for selection and citation by AI tools that deliver instant answers rather than search results.

Q: Why is GEO important for student recruitment in the age of AI search?

A: Generative AI search is already reshaping how prospective students discover, evaluate, and select postsecondary institutions. GEO (Generative Engine Optimization) equips institutions to remain visible and competitive in this changing environment.