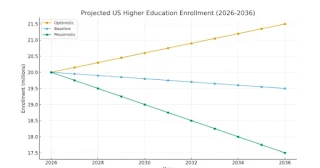

At Higher Education Inquirer, our focus on the college meltdown has always pointed beyond collapsing enrollments, rising tuition, and institutional dysfunction. Higher education has served as a warning signal — a visible manifestation of a far deeper crisis: the moral decay and dehumanization of society, compounded by a profound failure of courage among those with the greatest power and resources.

This concern predates the current moment. Through our earlier work at American Injustice, we chronicled how American institutions steadily abandoned ethical responsibility in favor of profit, prestige, and political convenience. What is happening in higher education today is not an anomaly. It is the predictable outcome of decades of moral retreat by elites who benefit from the system while refusing to challenge its injustices.

Permanent War and the Moral Abdication of Leadership

Wars in Gaza, Ukraine, and Venezuela reveal a world in which human suffering has been normalized and strategically managed rather than confronted. Civilian lives are reduced to abstractions, filtered through geopolitical narratives and sanitized media frames. What is most striking is not only the violence itself, but the ethical cowardice of leadership.

University presidents, policymakers in Washington, and financial and technological elites rarely speak with moral clarity about war and its human costs. Institutions that claim to value human life and critical inquiry remain silent, hedging statements to avoid donor backlash or political scrutiny. The result is not neutrality, but complicity — a tacit acceptance that power matters more than people.

Climate Collapse and the Silence of Those Who Know Better

Climate change represents an existential moral challenge, yet it has been met with astonishing timidity by those most capable of leading. Universities produce the research, model the risks, and educate the future — yet many remain financially entangled with fossil fuel interests and unwilling to confront the implications of their own findings.

Student demands for divestment and climate accountability are often treated as public-relations problems rather than ethical imperatives. University presidents issue vague commitments while continuing business as usual. In Washington, legislation stalls. On Wall Street, climate risk is managed as a portfolio concern rather than a human catastrophe. In Silicon Valley, technological “solutions” are offered in place of systemic change.

This is not ignorance. It is cowardice disguised as pragmatism.

The Suppression of Student Protest and the Fear of Moral Clarity

The moral vacuum at the top becomes most visible when students attempt to fill it. Historically, student movements have pushed institutions toward justice — against segregation, apartheid, and unjust wars. Today, however, student protest is increasingly criminalized.

Peaceful encampments are dismantled. Students are arrested or suspended. Faculty are intimidated. Surveillance tools track dissent. University leaders invoke “safety” and “order” while outsourcing enforcement to police and private security. The message is unmistakable: moral engagement is welcome only when it does not challenge power.

This is not leadership. It is risk aversion elevated to institutional doctrine.

Mass Surveillance and the Bureaucratization of Fear

The expansion of mass surveillance further reflects elite moral failure. From campuses to corporations, human beings are monitored, quantified, and managed. Surveillance is justified as efficiency or security, but its deeper function is control — discouraging dissent, creativity, and ethical risk-taking.

Leaders who claim to champion innovation quietly accept systems that undermine autonomy and erode trust. In higher education, surveillance replaces mentorship; compliance replaces curiosity. A culture of fear takes root where moral courage once should have flourished.

Inequality and the Insulation of Elites from Consequence

Extreme inequality enables this cowardice. Those at the top are shielded from the consequences of their decisions. University presidents collect compensation packages while adjuncts struggle to survive. Wall Street profits from instability it helps create. Silicon Valley builds tools that reshape society without accountability. Washington dithers while communities fracture.

When elites are insulated, ethical standards erode. Moral responsibility becomes optional — something to be invoked rhetorically but avoided in practice.

Social Media, AI, and the Automation of Moral Evasion

Social media and Artificial Intelligence accelerate dehumanization while providing cover for inaction. Platforms reward outrage without responsibility. Algorithms make decisions without accountability. Leaders defer to “systems” and “processes” rather than exercising judgment.

In higher education, AI threatens to further distance leaders from the human consequences of their choices — allowing automation to replace care, metrics to replace wisdom, and efficiency to replace ethics.

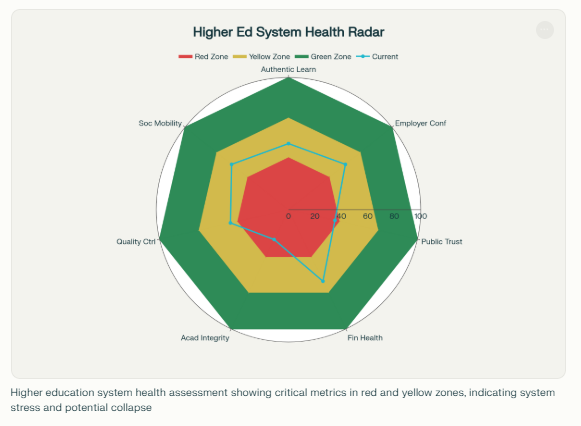

The Crisis Beneath the Crisis

The college meltdown is not simply a failure of policy or finance. It is a failure of moral leadership. Those with the most power — university presidents, elected officials, financiers, and technologists — have repeatedly chosen caution over conscience, reputation over responsibility, and silence over truth.

War without moral reckoning. Climate collapse without leadership. Protest without protection. Surveillance without consent. Inequality without accountability.

These are not accidents. They are the results of decisions made — and avoided — by people who know better.

Toward Moral Courage and Rehumanization

Rehumanization begins with courage. It requires leaders willing to risk prestige, funding, and influence in defense of human dignity. Higher education should be a site of ethical leadership, not an echo of elite fear.

This means defending student protest, confronting climate responsibility honestly, rejecting dehumanizing technologies, and placing human well-being above institutional self-preservation. It means leaders speaking plainly about injustice — even when it is inconvenient.

Our concern at Higher Education Inquirer — and long before that, at American Injustice — has always been this: What happens to a society when those with the greatest power lack the courage to use it ethically?

Until that question is confronted, the college meltdown will remain only one visible fracture in a far deeper moral collapse.