Join 2,968 other subscribers

Categories

Archives

This HEPI blog was kindly authored by Joanna Hart, Products, Services, and Innovation Director at the Mauve Group.

In the last couple of months, the UK Government has unveiled a 10-year, Modern Industrial Strategy and published an Immigration whitepaper, which referenced expanding visa pathways such as the High Potential Individual and Global Talent visas. The industrial strategy aims to attract highly skilled global talent in eight priority sectors, with a strong focus on technology and innovation. Collectively, these efforts to attract global graduates are undercut by new barriers facing international undergraduate students.

Ongoing changes to the Skilled Worker visa, including steep increases to salary thresholds, and tighter restrictions on dependents, combined with proposals to shorten the Graduate Visa, and introduce a controversial 6% international student levy, create mounting financial and reputational pressure on UK universities, while also deterring international undergraduates.

In response, institutions are turning to establishing overseas campuses to offset domestic shortfalls and attract local talent who may still benefit from expanded UK visa pathways post-graduation. While attracting high-level international talent is valuable for addressing skills gaps in the UK, it must be part of a broader, symbiotic strategy. One that nurtures international students from undergraduate level through to employment to ensure UK higher education remains globally competitive.

An important step in the much-needed long-term strategy is the implementation of expanded visa pathways such as the High Potential Individual (HPI) visa and the visa, traditionally for internationally educated post-graduates and entrepreneurs.

The High Potential Individual (HPI) visa is a UK immigration pathway designed for recent graduates from 40 top global universities, providing the opportunity to live and work in the UK for several years. At present, 47% of universities on the list are from the US, with just one institution from the entire southern hemisphere featured.

The Immigration whitepaper released in May and the UK government’s industrial strategy referenced extending the HPI visa to a wider selection of global universities. According to the UK government, it intends to roll out a ‘capped and targeted expansion of the HPI route for top graduates, doubling the number of qualifying universities.’ However, we do not yet know whether this expansion will be based on global league tables or geographic location.

The Innovator Founder visa offers the opportunity for founders of new, innovative, viable and scalable businesses to operate in the UK for three years. Traditionally, it facilitates incoming innovation, but the newly announced UK industrial strategy suggested the Innovator Founder Visa would be reviewed to make it easier for entrepreneurial talent currently studying at UK universities to be eligible. Details are yet to be disclosed but recent figures reveal that the average Innovator Founder Visa application success rate to the UK is almost 88%. While this is significant, it is not as high as other visa types, such as the Skilled Worker Visa, which is 99%. While the overall approval rate for Innovator Founder Visa applications sits at 88%, this figure can be misleading. The critical bottleneck is at the endorsement stage the first hurdle in the process, where the success rate drops sharply to just 36%

Changes to visa pathways for domestically educated international students, including the Skilled Worker and Graduate visas, may result in applicants feeling short-changed. For example, it has been proposed that the standard length of the Graduate visa, which allows international students to remain working in the UK at the beginning of their careers, be reduced from two years to 18 months. If implemented, it may make it hard to secure a career after studying in the UK.

Meanwhile, effective from the 22nd July 2025, the minimum salary threshold for the Skilled Worker visa will rise to £41,700. Occupation-specific salary thresholds will also increase by about 10%, with the minimum skills requirements raised to Royal Qualifications Framework (RQF) level 6 for new applicants. Prior to the changes, between 30 and 70 per cent of graduate visa holders in employment may not have been working in RQF level 6 or above occupations. Although there are some discounted thresholds for PhD students, especially in STEM fields, these changes are set to exclude many current Skilled Worker visa holders.

One of the major drawbacks comes from the announcement that the government is considering introducing a 6% levy on higher education provider income from international students. It is likely that universities will be forced to consider passing these costs onto international students. The UK’s higher education sector generates £22 billion annually from international students and education, making it a valuable export to the UK in an increasingly competitive global market. The proposed levy risks discouraging international students and undermining this critical source of economic growth.

Many institutions will already have factored in price increases to account for rising costs going forward, making an additional 6% unfeasible.

Numerous universities are already struggling financially, with courses and entire departments being cut. With the possibility of a highly reduced international student body due to the levy and further changes to graduate visa pathways, these institutions face increased strain, meaning even more drastic cuts may be imminent.

With an emphasis on higher visa thresholds, rising costs and the controversial 6% levy on international fees, UK universities face growing challenges to remain competitive in the global education landscape.

In response, many are rethinking their models, with institutions like the Universities of Liverpool and Southampton establishing campuses in Bengaluru and Gurugram, India, respectively. UK Universities operate 38 campuses across 18 countries, educating over 67,750 students abroad. Embracing international collaboration not only broadens the research opportunities available to UK universities but also supports financial sustainability and preserves the UK’s reputation as a global education powerhouse. By establishing overseas campuses and hubs, the UK’s academic influence extends well beyond its borders. This pivot will provide opportunities for international students to receive UK-affiliated accreditations, potentially giving them greater access to selective UK visa pathways post-graduation.

To adapt, higher education must develop a more integrated approach; one that links international recruitment, offshore campuses, and expanded visa pathways in a cohesive, long-term strategy. This means not only attracting global graduates but supporting students from undergraduate level through to employment, driving opportunity and innovation in the UK.

If UK institutions are to remain global leaders, they must work with the government to ensure that opportunity does not begin at graduation; it begins at enrolment. By nurturing this full pipeline, universities can continue to feed the skilled workforce envisioned in the new industrial strategy.

A new study from ApplyBoard has shown the number of students leaving Pakistan to join universities in countries such as the UK and US has grown exponentially in the past few years, with student visas issued to Pakistani students bound for the ‘big four’ nearly quadrupling from 2019 to 2025.

“One of the most striking findings is just how rapid and resilient Pakistan’s growth has been across major study destinations,” ApplyBoard CEO Meti Basiri told The PIE News.

“The rise of Pakistani students is a clear signal that global student mobility is diversifying beyond traditional markets like India and China,” he said.

The question is, why?

A large factor is Pakistan’s young population – 59%, or roughly 142.2 million people, are between the ages of five and 24, making it one of the youngest populations in Asia.

Additionally, due to economic challenges faced by Pakistan, many young people see international education as a necessity in order to succeed financially, even with Pakistan’s economic growth and gradual stabilisation – which has a possibility of slightly decreasing the overall movement between countries in the future.

The UK has remained the most popular destination for Pakistani students even through Covid-19, with Pakistan rising to become the UK’s third largest source country in 2024.

Visas issued to Pakistani students have grown from less than 5,500 to projected 31,000 this year, an increase of over 550% from 2019 to 35,501 in 2024.

Some 83% of students chose postgraduate programs, with the most popular being business courses, but in recent years statistics show a shift towards computing and IT courses.

This trend aligns with the growth of the UK’s tech sector, which is now worth more than 1.2 trillion pounds, with graduates set to aid further growth in the coming years.

“In the US, F-1 visas for Pakistani students are on track to hit an all-time high in FY2025,” said Basiri, with STEM subjects the most popular among the cohort.

This aligns with the US labour market, where STEM jobs have grown 79% in the last 30 years.

Basiri highlighted the “surprising” insight that postgraduate programs now make up the majority of Pakistani enrolments, particularly in fields of IT, engineering and life sciences. “This reflects a deliberate and career-driven approach to international education,” he said.

Such an approach is true of students across the world, who are becoming “more intentional, choosing destinations and programs based on affordability, career outcomes, and visa stability, not just brand recognition,” said Basiri.

The rise of Pakistani students is a clear signal that global student mobility is diversifying beyond traditional markets like India and China

Meti Basiri, ApplyBoard

Canada, unlike the US and UK, has welcomed far fewer Pakistani students, most likely due to the introduction of international student caps. ApplyBoard also suspects Pakistani student populations to drop further in the coming years, it warned.

Similarly, the amount of visas issued to Pakistani students has also dropped in Australia after high demand following the pandemic.

Germany, however, has experienced rising popularity, a 70% increase in popularity over five years amongst Pakistani students.

One of the biggest factors for this is their often tuition-free public post secondary education, according to ApplyBoard, as well as the multitude of engineering and technology programs offered in Germany.

What’s more, though smaller in scale, the UAE has seen a 7% increase in Pakistani students in recent years, thanks, in part to “geographic proximity, cultural familiarity and expanding institutional capacity,” said Basiri.

Studiosity’s ninth annual Student Wellbeing Survey, conducted by YouGov in November 2024, gathered insights from university students on their experiences and concerns, and made recommendations to senior leaders. This global research included panels from Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, the UAE, the UK and the US (see below for the country sample size breakdown).

The report highlights key learning on AI’s rapid integration into higher education and its impact on student wellbeing. The following are the key takeaways, specifically examining country-specific differences in student experiences with AI, alongside broader issues of stress, connection, belonging, and employability.

AI is now a pervasive tool in higher education, with a significant 79% of all students reporting using AI tools for their studies. While usage is high overall, the proportion of students saying they use AI ‘regularly’ to help with assignments shows interesting variations by country:

This greater scepticism towards AI among UK students also shows up elsewhere, with students in the UK least likely among the eight countries to expect their university to offer AI tools.

However, the widespread adoption of AI tools is linked to considerable student stress. The survey found that 68% of students report experiencing personal stress as a result of using AI tools for their coursework. From free text comments, this might be for a number of reasons, including the fear they might be unintentionally breaking the rules; there are also concerns that universities are not moving fast enough to provide AI tools, leaving students to work out for themselves how best to use AI tools. This highlights that navigating the effective and appropriate use of AI is a significant challenge that requires support.

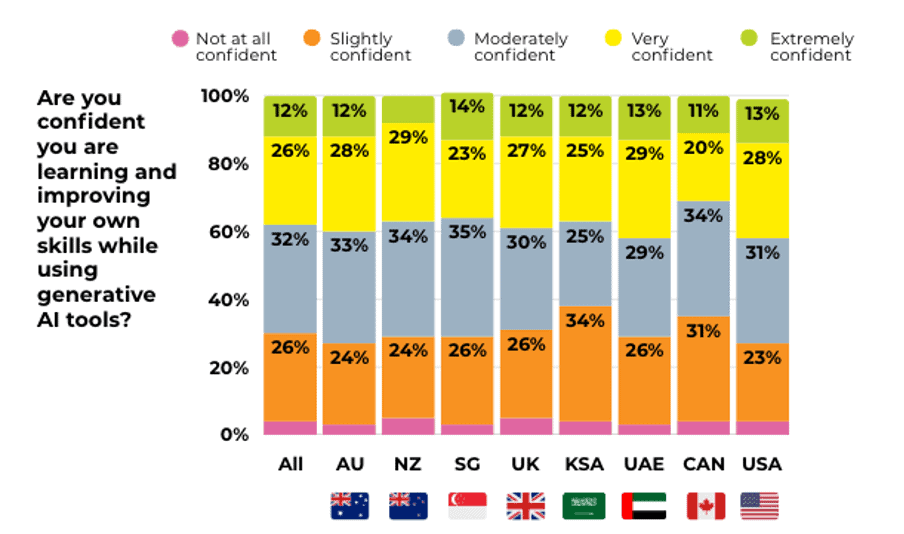

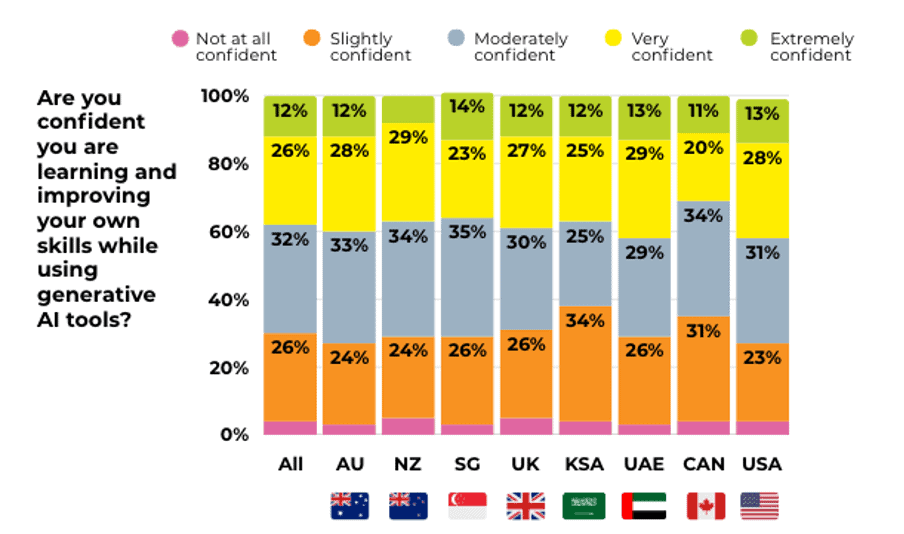

Furthermore, the way AI is currently being used appears to be affecting students’ confidence in their own learning. Some 61% feel only ‘moderately’ or less confident that they are genuinely learning and improving their own skills when using generative AI.

Perhaps as a result of this uncertainty, students often seek ‘confidence’ when using university-provided AI support, desiring guided tools that help them check their understanding and validate their genuine learning progress. This motivation was particularly strong in countries like:

This suggests a tension between unstructured AI use (linked to lower learning confidence) and the student desire for confidence-building support (which AI, when properly designed for learning, offers).

Perceptions of how well universities are adapting to AI also vary globally, with 56% of students overall feeling their institutions are adapting quickly enough. However, scepticism is notably higher in certain regions:

Conversely, students in other countries feel their university is adapting fast enough to include AI support tools for study:

While AI contributes to stress, study stress is a broader, multi-faceted challenge for student wellbeing, with frequency and causes differing significantly across countries. Students reported experiencing stress most commonly on a weekly basis (29% overall), with more students than average in Australia and New Zealand (both 33%) experiencing stress on a weekly basis. However, the intensity increases elsewhere:

The top reasons for general study stress also vary, pointing to the diverse pressures students face:

A sense of belonging is a crucial component of student wellbeing, and the survey revealed variations across countries. Students in Australia (62%) and the UK (65%) reported lower overall belonging levels compared to the global average. What contributes to belonging also differs:

The study also explored direct connections, addressing concerns that AI might reduce human interaction. Students were largely neutral or unsure if generative AI impacted their interactions with peers and teachers (including 63% of students in the UK and 55% in New Zealand). In contrast, students in Saudi Arabia (64%) and the UAE (61%) were most likely to report more interaction due to AI use, followed by Singapore (42%) and the USA (41%).

Beyond AI’s influence on connection, the survey found that four in ten students (42%) were not provided a mentor in their first year, although over half (55%) would have liked one. Difficulty asking questions of other students was also mentioned by one in ten (13%) students overall. This difficulty was reported more by:

Employability is another key area impacting student confidence and overall wellbeing as they look towards the future. The survey found that 59% of students are confident in securing a job within six months of graduation, an increase from 55% in 2024, though concerns remain higher in Canada and the UK. Overall, 74% agree their degree is developing necessary future job skills, although Canadian students were less confident here (68%). Specific concerns about the relevance of a job within six months were more pronounced among:

The YouGov-Studiosity survey provides valuable data highlighting the complex reality of student wellbeing in the current higher education landscape. Rapid AI adoption brings new sources of stress and impacts confidence in learning, adding to existing pressures from general study demands, financial concerns, belonging, connection, and employability anxieties. These challenges, and what supports students most effectively, vary significantly by country. Universities must respond to this complex picture by developing tailored support frameworks that guide students in navigating AI effectively, while also bolstering their sense of belonging, facilitating connections, addressing mental health needs, and supporting their confidence in future careers, in ways responsive to diverse national contexts.

By country totals: Australia n= 1,234: Canada n= 1,042: New Zealand n= 528: Saudi Arabia n= 511: Singapore n= 1,027: United Arab Emirates n=554: United Kingdom n= 2,328: United States n= 3,000

You can download further Global Student Wellbeing reports by country here.

Studiosity is a HEPI Partner. Studiosity is AI-for-Learning, not corrections – to scale student success, empower educators, and improve retention with a proven 4.4x ROI, while ensuring integrity and reducing institutional risk.

WEDNESDAY, JULY 30 | 6:30PM | PARISH HALL (Boston)

Join us for a special presentation by Dr. Kuemmerle, a neurologist at Children’s Hospital and the co-founder of Doctors Against Genocide. Founded in 2023, Doctors Against Genocide is a coalition of healthcare professionals who seek to unite their voices in uproar against the genocide in Gaza. This presentation will be livestreamed on our Youtube channel.

Doctors Against Genocide is currently raising $737,000 to fund the construction of a 140-bed field hospital with 4 operating rooms on the grounds of Al-Shifa hosptial. Gaza’s largest hospital has been bombed, burned, and pushed past its limits. After the forced shutdown of the Indonesian, Al-Awda, and Kamal Adwan hospitals, Al-Shifa is the last major hospital left standing in North Gaza.

Right now, occupancy is at 200–300%. Patients are being treated on floors, in hallways, and tents. There are no more beds. No more space. But there is a way forward with your help. If you would like donate, please visit: https://doctorsagainstgenocide.org/donate.

Eli Kronenberg is a rising junior and a FIRE summer intern.

In the last decade, the rise of the mercenary spyware industry has created a potent new weapon for authoritarian regimes bent on silencing dissent. Represented most prominently by the Israeli-based NSO Group and its flagship spyware Pegasus, surveillance malware is often sold to the world’s most repressive governments with little thought given to the nature of its eventual use.

Regimes like those in Saudi Arabia and Egypt have long track records of suppressing political opposition and independent journalism. When they acquire state-of-the-art surveillance technology, the result is a crackdown on free expression worldwide, carried out using the devices in our very pockets. And because the surveillance is secret and largely undetectable, it impacts anyone with a reason to suspect that the government might not like what they have to say.

What is mercenary spyware?

Mercenary spyware is a type of malicious software developed and sold by private companies to governments. Unlike general malware, which spreads widely and somewhat randomly, mercenary spyware is designed to infiltrate specific devices and extract information.

The University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab has published numerous reports explaining how spyware like Pegasus is used to hack the personal devices of political opponents in retaliation for criticizing the government. Victims include an Italian journalist critical of the Meloni government, an Egyptian opposition politician with presidential ambitions, dozens of Catalan separatist leaders in Spain, Mexican journalists investigating presidential corruption, and even a Saudi dissident living in exile in Canada.

“The consequences that we’ve seen in our research are profound,” said Ronald Deibert, the director of the Citizen Lab. “People are afraid to engage over social media, to use the internet, paranoid about their surroundings, about their social relationships. There’s an obvious chilling effect.”

Here’s how it works: Mercenary spyware companies like NSO Group search technological operating systems for novel security vulnerabilities known as “zero-days,” which can be used to infiltrate products as ubiquitous as Apple iPhones. Then, they develop spyware designed to exploit these zero-days and sell it to governments, ostensibly for law enforcement and intelligence agencies to use for legitimate data-gathering purposes.

In practice, governments with long histories of repression often abuse spyware to hack the devices of anti-government activists, journalists, and other members of civil society. And, even for democratic regimes who preach tolerance of dissent, the temptation of spyware capabilities often proves too powerful.

All it takes is one click on a phishing message for spyware to be implanted onto a device. From there, governments can read all of the target’s communications, track the device’s location, and secretly turn on the camera and microphone to listen to live conversations — without the victim receiving any indication that their device has been compromised.

In recent years, spyware has evolved past the point of needing victims to fall for fake links, instead relying on “zero-click” attacks which automatically implant the spyware without requiring the user to do anything. Not even the most meticulous digital hygiene measures can keep those who have drawn the government’s ire safe in this day and age.

“I imagine from the perspective of an operative who’s using this type of product, how addictive it must be,” Deibert said. “It’s almost godlike to be able to just drop into somebody’s life, find out everything about them, watch what they’re doing, turn on the microphone, turn on the camera. That is extremely compelling from an intelligence collection point of view, and opens up all sorts of opportunities that otherwise wouldn’t exist for those types of operatives, which explains why the business is so lucrative.”

While today’s surveillance agents have shiny new tools, their tactics are tried and true. The Nazis famously used IBM punch cards to categorize citizens by ethnicity and other metrics, as well as wiretaps to track Jews, political dissidents, and other “undesirables.” In East Germany, the Stasi used hidden cameras and bugging devices to maintain files on more than one-third of the population. They even stored body odors to identify dissidents using dogs. The Chinese Communist Party uses facial recognition software so advanced they caught a suspect in a crowd of 60,000 people — and that was seven years ago.

In 2025, it is easier than ever to invade the private lives of those who dare speak up against public officials. The mercenary spyware industry emerged in the early 2010s, coinciding with the rise of social media-enabled revolutions like the Arab Spring. For regimes seeking to quell political opposition but lacking the technological means to effectively control it, mercenary spyware companies provided a saving grace.

“What this market offers them is the ability to leapfrog ahead in surveillance capacity, in espionage capacity, effectively drawing from some of the world’s most well-trained, sophisticated veterans of intelligence agencies,” Deibert said.

Reining in the industry

Fortunately for supporters of free expression, the U.S. has taken concrete steps to crack down on mercenary spyware companies. In 2023, former President Joe Biden issued an executive order directing agencies to cease procuring commercial spyware that poses a threat to human rights or national security. Twenty-two countries signed on to the Biden administration’s “Joint Statement on Efforts to Counter the Proliferation and Misuse of Commercial Spyware,” pledging to implement similar guardrails.

The industry’s biggest fish, NSO Group, was added to the Commerce Department’s trade blacklist in 2021, stifling the company’s business prospects on American soil. NSO has also been dealt blows by the courts, most recently being ordered to pay WhatsApp $170 million in damages after its spyware was used to hack over 1,000 accounts on the messaging app.

“To me, that was all a roadmap of how you go about effectively reining in this wild west that’s causing all sorts of harm,” Deibert said of these efforts.

The bad news? While some of the world’s biggest spyware developers have been wounded, they won’t give up easily. NSO Group recently hired a new lobbying firm with the mission of reigniting its relationship with Washington lawmakers and reversing the novel regulations, according to an April report by WIRED.

Those efforts have been rebuffed for now. The Trump administration canceled a meeting with NSO officials in May, citing the company being “not forthcoming in its motives for seeking the meeting,” according to an unnamed official in the Washington Post.

Still, spyware companies and their opportunistic governmental clients thrive when operating from the shadows. The U.S. must remain vigilant and further crack down on companies whose spyware is used to spy on civil society, ensuring that political dissidents worldwide can speak without the threat of dictators — or even democratically elected governments — invading their pockets and upending their lives.

RESTON, Va.(GLOBE NEWSWIRE) — K12, a portfolio brand of Stride, Inc. has been recognized for its steadfast commitment to quality education. In a recent review by Cognia, a global nonprofit that accredits schools, K12 earned an impressive Index of Education Quality (IEQ) score of 327, well above the global average of 296. Cognia praised K12 for creating supportive environments where students are encouraged to learn and grow in ways that work best for them.

For over 25 years, K12 has been a pioneer in online public education, delivering flexible, high-quality learning experiences to families across the country. Having served more than 3 million students, K12 has helped shape the future of personalized learning. This long-standing presence in the field reflects a deep understanding of what families need from a modern education partner. The recent Cognia review further validates K12’s role as a trusted provider, recognizing the strength of its learning environments and its commitment to serving all students.

“What stood out in this review is how clearly our learning environments are working for students,” said Niyoka McCoy, Chief Learning Officer at Stride, Inc. “From personalized graduation plans to real-time feedback tools and expanded course options, the Cognia team saw what we see every day, which is students being supported in ways that help them grow, stay engaged, and take ownership of their learning.”

K12’s impact extends well beyond the virtual classroom. In 2025, the organization was honored with two Gold Stevie® Awards for Innovation in Education and recognized at the Digital Education Awards for its excellence in digital learning. These awards highlight K12’s continued leadership in delivering meaningful, future-focused education. What sets K12-powered online public schools apart is a curriculum that goes beyond the basics, offering students access to STEM, Advanced Placement, dual-credit, industry certifications, and gamified learning experiences. K12’s program is designed to spark curiosity, build confidence, and help students thrive in college, careers, and life.

Through student-centered instruction and personalized support, K12 is leading the way in modern education. As the learning landscape evolves, K12 adapts alongside it, meeting the needs of today’s students while shaping the future of education.

To learn more about K12 and its accredited programs, visit k12.com.

About Stride, Inc.

Stride Inc. (LRN) is redefining lifelong learning with innovative, high-quality education solutions. Serving learners in primary, secondary, and postsecondary settings, Stride provides a wide range of services including K-12 education, career learning, professional skills training, and talent development. Stride reaches learners in all 50 states and over 100 countries. Learn more at Stridelearning.com.

Imagine a world where anyone who wants to work in a different city or country can simply share all their skills and learning achievements – including those obtained through formal and informal settings – in a unified, digital format with a prospective employer. Imagine employers having an easy way to verify a candidate’s diverse skills and clearly being able to identify the applicable competencies across international boundaries.

For anyone who has ever tried to work abroad and navigated all the paperwork and certification processes, this could sound like a very futuristic idea. However, this is precisely what digital learning portfolios are making possible – fostering student mobility and facilitating cross-institutional collaboration among universities worldwide to dynamise the global workforce.

A digital learning portfolio is an online collection of a student’s verified skills, qualifications and learning experiences, often captured across various formal and informal settings. By functioning as a form of digital credentialling, this portfolio allows students to document and present their learning achievements in a unified, digital format. Students can seamlessly showcase a combination of academic degrees, microcredentials, short courses and experiential learning, giving domestic or international prospective employers a more comprehensive view of their capabilities.

As more educational institutions look to expand their international reach, digital credentials present a transformational opportunity to track learning experiences and position students more competitively in the global job markets. With a structured, verifiable digital portfolio, students can demonstrate their formal and informal learning experiences in real time and highlight an array of microcredentials, skills and qualifications.

Global collaboration in higher education is growing steadily, marking a crucial step for universities – even as countries like the UK, Canada, and Australia impose tighter restrictions on international students. This trend highlights the increasing importance of cross-border partnerships in advancing research, innovation, and academic excellence.

Students continue to seek study-abroad opportunities and universities are increasingly partnering across borders to offer joint programmes and exchange initiatives. This has been highlighted in Europe with programmes like the European Universities Initiative. However, differing approaches to credentialling can often pose challenges. These challenges are further compounded by the fact that some institutions still rely on traditional methods—such as print and paper—to manage and distribute official transcripts and certificates. This not only slows down the process but also hinders the seamless exchange of academic records across borders.

Digital credentials and badges can help address these issues by offering a consistent and verifiable way for students to record their achievements. This consistency simplifies joint programmes, exchange students and curriculum alignment across countries. With a universal standard, students can more easily navigate international educational pathways and access opportunities that may have been limited by varying credentialing systems.

For institutions, investing in technology to leverage digital credentials and badges will streamline the process of building and strengthening global partnerships. They can provide a reliable way to attract international students, create robust pathways to global learning opportunities and ensure smooth credit transfers between institutions in different countries. This can significantly prevent credential fraud and enhance an institution’s global appeal, as students can trust that their academic achievements and skills will be recognised no matter where they go.

Today’s employers are gradually favouring skills over traditional degrees and looking for agility and flexibility in their hiring processes. Digital credentialling supports a skills-driven hiring process that’s more responsive to the needs of a global, fast-evolving workforce.

Digital credentials and badges will become essential for documenting and validating shorter, targeted learning experiences such as microcredentials, apprenticeships and other skill-focused learning experiences that may not necessarily fit within traditional degree frameworks. This transparency helps employers better assess candidates based on relevant, demonstrated competencies.

One of the key benefits of digital credentials is their ability to support lifelong career mobility. As people change roles, industries, and even countries throughout their careers, having the opportunity to access 24/7 digital credentials will provide them with an adaptable, portable record of qualifications. This flexibility empowers students to carry their skills and experiences with them, regardless of where their careers take them.

For these students, a digital portfolio that evolves with them throughout their lives opens doors to greater global mobility and ensures that achievements from one part of the world are recognised and respected in another, strengthening graduates’ ability to apply to job opportunities abroad, or pursue additional international degrees, short courses or microcredentials and thrive in diverse job markets.

While AI is reshaping industries by automating routine tasks, leading to the evolution of existing roles and the creation of new ones, higher education institutions must focus on the importance of lifelong learning, as continuous skill development becomes essential in an AI-driven economy.

More than ever, universities need to invest in modern cloud-based virtual learning environments that can support and scale a lifelong learning strategy, including microcredentials and digital credentials. By offering students the tools to maintain dynamic portfolios throughout their careers, institutions can better prepare graduates to succeed in an interconnected and global workforce and stay relevant.

Education is no longer confined to traditional phases of life; it’s a continual journey of growth and adaptation. By enabling seamless transitions between learning opportunities and career stages, universities can empower individuals to thrive in a world where constant upskilling is essential, and skill recognition should go beyond the boundaries of traditional learning.

In today’s interconnected world, digital credentials and learning portfolios provide a structured way to document and share skills, supporting both students’ career ambitions and employers’ workforce needs across the globe. Institutions and employers must collaborate to integrate digital credentials into the skills journey, ensuring a seamless link between education and workforce readiness to dynamically prepare students for a global economy, paving the way for a more adaptable, skilled and mobile workforce.

As UK education minister Bridget Phillipson has rightly acknowledged, the UK is home to many world-class universities.

And the country’s excellence in higher education is yet again on display in the QS World University Rankings 2026.

Imperial College London, University of Oxford, University of Cambridge and UCL all maintain their places in the global top 10 and 17 of the total 90 UK universities ranked this year are in the top 100, two more than last year.

The University of Sheffield and The University of Nottingham have returned to the global top 100 for the first time since 2023 and 2024 respectively.

But despite improvements at the top end of the QS ranking, some 61% of ranked UK universities have dropped this year.

Overall, the 2026 ranking paints a picture of heightening global competition. A number of markets have been emerging as higher education hubs in recent decades – and the increased investment, attention and ambition in various places is apparent in this year’s iteration.

Saudi Arabia – whose government had set a target to have five institutions in the top 200 by 2030 – has seen its first entry into to top 100, with King Fahd University of Petroleum & Minerals soaring 34 places to rank 67th globally.

Vietnam, a country that is aiming for five of its universities to feature in the top 500 by the end of the decade, has seen its representation in the rankings leap from six last year to 10 in 2026.

China is still the third most represented location in the world in the QS World University Rankings with 72 institutions, behind only the US with 192 and the UK with 90. And yet, close to 80 institutions that are part of the Chinese Double First Class Universities initiative to build world-class universities still do not feature in the overall WUR.

Saudi Arabia currently has three institutions in the top 200, while Vietnam has one in the top 500. If these countries succeed in their ambitions, which universities will lose out among the globe’s top in five years’ time?

The financial pressure the UK higher education is facing is well documented. Universities UK (UUK) recently calculated that government policy decisions will result in a £1.4 billion reduction in funding to higher education providers in England in 2025/26. The Office for Students’s warning that 43% of England’s higher education institutions will be in deficit this academic year is often cited.

Some 19% UK university leaders say they have cut back on investment in research given the current financial climate, and an additional 79% are considering future reductions.

On a global scale, cuts like this will more than likely have a detrimental impact on the UK’s performance in the QS World University Ranking – the world’s most-consulted international university ranking and leading higher education benchmarking tool.

The 2026 QS World University Rankings already identify areas where UK universities are behind global competitors.

With a 39.2 average score in the Citations per Faculty area, measuring the intensity of research at universities, the UK is already far behind places such as Singapore, the Netherlands, Hong Kong, Australia and Mainland China, all of which have average scores of at least 70.

In Faculty Student Ratio, analysing the number of lecturers compared to students, the UK (average score of 26.7) is behind the best performing locations such as Norway (73.7), Switzerland (63.8) and Sweden (61.8).

While Oxford, Cambridge and LSE all feature in the global top 15 in Employment Outcomes and 13 UK universities feature in the top 100 for reputation among employers, other universities across the world are improving at a faster rate than many UK universities.

And, despite its historical dominance in the global education lens, global competitors are catching up with UK higher education in international student ratio and international faculty.

While 74% of UK universities improved in the international student ratio indicator in 2022, the last few years have identified a weakening among UK institutions. In 2023, 54% of UK universities fell in this area, in 2024, 56% dropped and in 2025, 74% declined. And in 2026, 73% dropped.

The government in Westminster is already aware that every £1 it spends on R&D delivers £7 of economic benefits in the long term and, for that reason, it prioritised spending to rise to £22.6bn in 2029-30 from £20.4bn in 2025-26.

But without the financial stability at higher education institutions in question, universities will need more support going ahead beyond support for their research capabilities. Their role in developing graduates with the skills to propel the UK forward is being overlooked. The QS 2026 World University Ranking is already showing that global peers are forging ahead. UK universities will need the right backing to maintain their world-leading position.

Hello everyone, and welcome to the World of Higher Education podcast. I’m Tiffany MacLennan, and if you’re a faithful listener, you know what it means when I’m the one opening the episode—this week, our guest is AU.

We’re doing a year in review, looking at some of the global higher education stories that stood out in 2024—from massification to private higher education, from Trump’s international impact to the most interesting stories overall. But I’ll pass it over to Alex.

The World of Higher Education Podcast

Episode 3.35 | The Year the Money Ran Out: Global Higher Ed Review

Tiffany MacLennan (TM): Alex, you’re usually the one asking the questions, but today you’re in our hot seat.

Alex Usher (AU): It’s technically the same seat I’m always in.

TM: Fair point. But today, you’re in the question seat. Let’s start with the global elephant in the room.

Last week, we talked at length with Brendan Cantwell about the domestic effects of Donald Trump’s education policies. But what impacts are we seeing internationally? Are any countries or institutions actively trying to capitalize on the chaos in the U.S.? And if so, how serious are those efforts to poach talent and build their reputations?

AU: There are lots of countries that think they’re in a position to capitalize on it—but almost none of them are serious.

The question is: where is the real destruction happening in the United States? Where is the greatest danger? And the answer is in research funding. NIH funding is going to be down by a third next year. NSF funding is going to be down by more than 50%. So it’s the scientists working in STEM and health—those with the best labs in the world—who are suddenly without money to run programs.

But what are they supposed to do? Are there alternatives to labs of that scale? Are there alternatives to the perks of being a top STEM or health researcher at an American university?

Places like Ireland—well, Ireland has no research culture to speak of. The idea that Ireland is going to step in and be competitive? Or the Czech Republic? Or India, which keeps talking about this being their moment? Come on. Be serious. That’s not what’s happening here.

There might be an exodus—but it’s more likely to be to industry than to other countries. It’s not clear to me that there will be a global redistribution of this talent.

Now, the one group that might move abroad? Social scientists and humanities scholars. And you’ve already seen that happening—especially here in Toronto. The University of Toronto has picked up three or four high-profile American scholars just in the last little while.

Why? Because you don’t need to build them labs. The American lead in research came from the enormous amounts of money spent on infrastructure: research hospitals, labs—facilities that were world-class, even in unlikely places. Birmingham, Alabama, for example, has 25 square blocks of cutting-edge health research infrastructure. How? Because America spent money on research like no one else.

But they’re not doing that anymore. So I think a lot of that scientific talent just… disappears. It’s lost to academia, and it’s not coming back. And over the long term, that’s a real problem for the global economy.

TM: Sticking with the American theme, are there other countries that have been taking, well, I hesitate to say lessons, but have been adopting policies inspired by the U.S. since Donald Trump came to power? Or has it gone the other way—more like a cautionary tale of what not to do if you want to strengthen your education sector?

AU: I think the arrival of MAGA really made a lot of people around the world realize that, actually, having talented researchers in charge of things isn’t such a bad idea.

We saw that reflected in elections—in Canada, in Australia—where center-left governments that were thought to be in trouble suddenly pulled off wins. Same thing in Romania.

The one exception seems to be Poland. But even there, I’m not sure the culture war side of things was ever as intense as it was in the United States. In fact, the U.S. isn’t even the originator of a lot of this stuff—it’s Hungary. Viktor Orbán’s government is the model. The Project 2025 crew in the U.S. has made it pretty clear: they want American universities to look more like Hungarian ones.

And the Hungarian Minister of Higher Education has been holding press conferences around the world, claiming that everyone’s looking at Hungary as a model.

So, there’s definitely been a shift—America is moving closer to the Hungarian approach. But I don’t think anyone else is following them. Even in Poland, where there’s been political change, the opposition still controls the parliament, so it’s not clear anything dramatic will happen there either.

So no—I don’t think we’re seeing widespread imitation of U.S. education policy right now. Doesn’t mean it couldn’t happen—but we’re not there yet.

TM: One thing we’ve seen a lot of this year is talk—and action—around the massification of higher education. What countries do you think have made some of the most interesting moves in expanding access? And on the flip side, are there any countries that are hitting their capacity?

AU: Everyone who’s making progress is also hitting their capacity. That’s the key thing. Massification isn’t just a matter of saying, “Hey, let’s build a new school here or there.” Usually, you’re playing catch-up with demand.

The really interesting case for me is Uzbekistan. Over the past decade, the number of students has increased fivefold—going from about 200,000 to over a million. I’m not sure any country in the world has moved that fast before. That growth is driven by a booming population, rising wealth, and—crucially—a government that’s willing to try a wide range of strategies: working with domestic public institutions, domestic private institutions, international partners—whatever works. It’s very much a “throw spaghetti at the wall and see what sticks” approach.

Dubai is another case. It’s up 30% this year, largely driven by international students. That’s a different kind of massification, but still significant.

Then there’s Africa, where we’re seeing a lot of countries running into capacity issues. They’ve promised access to education, but they’re struggling to deliver. Nigeria is a standout—it opened 200 new universities this year. Egypt is another big one. And we’re starting to see it in Kenya, Tanzania, Ghana—places that have reached the level of economic development where demand for higher education takes off.

But here’s the catch: it’s not always clear that universal access is a good idea from a public policy standpoint. At certain stages of economic development, you can support 70% participation rates. At others, you’re doing well to sustain 20%. It really depends where you are.

And these are often countries with weak tax systems—low public revenue. So how do you fund it all? That’s a major challenge.

What we’re seeing in many places is governments making big promises around massification—and now struggling to keep them. I think that tension—between rising demand and limited capacity—is going to be a major story in higher education for at least the next three or four years.

TM: I think that leads nicely into my next question: what’s the role of private higher education in all of this?

Private institutions have been popping up more and more, and the conversation around them has only grown. Sometimes they’re filling important gaps, and sometimes they’re creating problems. But this year, we also saw some pretty major regulatory moves—governments trying to reassert control over what’s become a booming sector.

Do you see this as part of a broader shift? And what do you think it means for the future of private higher education?

AU: I don’t see a big shift in private education in less industrialized countries. What you’re seeing there is more a case of the public sector being exhausted—it simply can’t keep up with demand. So private providers show up to fill the gap.

The question is whether governments are regulating those providers in a way that ensures they contribute meaningfully to the economy, or if they’re just allowing bottom-feeders to flourish. And a lot of places struggle to get that balance right.

That said, there are some positive examples. Malaysia, for instance, has done a pretty good job over the years of managing its private higher education sector. It’s a model that other countries could learn from.

But I think the really interesting development is the growth of private higher education in Europe.

Look at Spain—tuition is relatively cheap, yet 25% of the system is now private. France has free tuition, but still, 25% of its system is private. In Germany, where tuition is also free, the private share is approaching 20%.

It’s a different kind of issue. Strong public systems can ossify—they stop adapting, stop responding to new needs. In Europe, there’s very little pressure on public universities to align with labor market demand. And rising labor costs can mean that public universities can’t actually serve as many students as they’d like.

France is a good example. It’s one of the few countries in Europe where student numbers are still growing significantly. But the government isn’t giving public universities more money to serve those students. So students leave—they say, “This isn’t a quality education,” and they go elsewhere. Often, that means going to private institutions.

We had a guest on the show at one point who offered a really interesting perspective on what private higher education can bring to the table. And I think that’s the fascinating part: you’d expect the private sector boom to be happening in a place like the U.S., with its freewheeling market. But it’s not. The big story right now is in Europe.

TM: Are there any countries that are doing private higher education particularly well right now? What would you say is the “good” private higher ed story of the year?

AU: That’s a tough one, because these things take years to really play out. But I’d say France and Germany might be success stories. They’ve managed to keep their top-tier public institutions intact while still allowing space for experimentation in the private sector.

There are probably some good stories in Asia that we just don’t know enough about yet. And there are always reliable examples—like Tecnológico de Monterrey in Mexico, which I think is one of the most innovative institutions in the Americas.

But I wouldn’t say there’s anything dramatically different about this year that marks a turning point. That said, I do think we need to start paying more attention to the private sector in a way we haven’t since the explosion of private higher education in Eastern Europe after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Back then, governments looked around and said, “Okay, we need to do something.” Their public universities—especially in the social sciences—were completely discredited after decades of Marxist orthodoxy. So they let the private sector grow rapidly, and then had to figure out how to rein it in over time.

Some countries managed that fairly well. Romania and Poland, for instance, have built reasonably strong systems for regulating private higher education—though not without some painful moments. Romania in particular had some pretty chaotic years. If you look up Spiru Haret University, you’ll get a sense of just how bad it can get when you completely let the market rip.

But now there are decent examples that other regions—especially Africa and Central Asia—can look to. These are areas where private education is going to be increasingly important in absorbing new demand.

The real question is: how do you translate those lessons from one context to another?

TM: Alex, when it comes to the least good stories of the year, it felt like the headlines were all the same: there’s no money. Budget cuts. Doom and gloom.

What crisis stood out to you the most this year, and what made it different from what we’ve seen in other countries?

AU: Well, I think Argentina probably tops the list. Since President Milei came into power, universities have seen their purchasing power drop by about 60%. It’s a huge hit.

When Milei took office, inflation was already high, and his plan to fix it was to cut public spending—across the board. That meant universities had to absorb the remaining inflation, with no additional support to help cushion the blow. And on top of that, Milei sees universities as hotbeds of communism, so there’s no political will to help.

It’s been brutal. So that’s probably the number one crisis just in terms of scale.

Kenya is another big one. The country has been really ambitious about expanding access—opening new universities and growing the system. But they haven’t followed through with adequate funding. The idea was that students would pick up some of the slack financially, but it turns out most Kenyan families just aren’t wealthy enough to make that work.

They tried to fill the gap with student loans, but the system couldn’t support it. And now there’s blame being placed on the funding formula. But the issue isn’t the formula—it’s the total amount of money being put into the system.

There’s a common confusion: some people understand that a funding formula is about dividing money between institutions. Others mistakenly think it dictates how much money the government gives in total. Kenya’s leadership seems to have conflated the two—and that’s a real problem.

Then you’ve got developed countries. In the UK, there have been lots of program closures. France has institutions running deficits. Canada has had its fair share of issues, and even in the U.S., problems were mounting before Trump came back into the picture.

We’ve almost forgotten the extent to which international students were propping things up. They helped institutions on the way up, and they’re now accelerating the downturn. That’s been a global issue.

And I know people are tired of hearing me say this, but here’s the core issue: around the world, we’ve built higher education systems that are bigger and more generous than anyone actually wants to pay for—whether through taxes or tuition.

So yeah, we’ve created some great systems. But nobody wants to fund them. And that’s the underlying story. It shows up in different ways depending on the country, but it’s the same problem everywhere.

TM: Do you think we’re heading into an era of global higher ed austerity, or are there some places that are bucking the trend?

AU: It depends on what you mean by “austerity.”

Take Nigeria or Egypt, for example—the issue there isn’t that they’re spending less on higher education. The issue is that demand is growing so fast that public universities simply can’t keep up. You see similar dynamics in much of the Middle East, across Africa, to some extent in Brazil, and in Central Asia. It’s not about cuts—it’s about the gap between what’s needed and what’s possible.

Then you have a different set of challenges in places with more mature systems—places that already have high participation rates. There, the problem is maintaining funding levels while demographics start to decline. That’s the situation in Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and parts of Europe. The question becomes: can you sustain your system when there are fewer students?

And then there’s a third category—countries that are still growing, but where governments just don’t want to spend more on higher education. That’s Canada, the United States, and the UK. Those systems aren’t necessarily shrinking, but they’re certainly under strain because of political choices.

But keep in mind—those are also among the richest countries in the world, with some of the best-funded universities to begin with.

In a way, what’s happening internationally mirrors what we saw in Canada with the province of Alberta. For many years, Alberta had post-secondary funding that was 40 to 50% above the national average. Then it started to come down toward the mean.

I think that’s what we’re seeing globally now. Countries like the UK, U.S., and Canada—whose systems were well above the OECD average in terms of funding—are being pulled back toward that average.

To us, it might feel like austerity. But if you’re in a country like Greece or Lithuania, and you look at how much money is still in the Canadian or UK system, you’d probably say, “I wish I had your problems.”

So I’d say we’re seeing three different dynamics at play—not a single, uniform trend.

TM: One of the most fun things about working at HESA is that we get to read cool stories for a good chunk of the time. What was the coolest or most unexpected higher education story you came across this year?

AU: I think my favorite was the story out of Vietnam National University’s business school. Someone there clearly read one of those studies claiming that taller people make more successful business leaders—you know, that there’s a correlation between CEO pay and height or something like that.

Same idea applies to politicians, right? Taller politicians tend to beat shorter ones. Canada, incidentally, has a lot of short politicians right now. Anyway, I digress.

At VNU in Hanoi, someone apparently took that research seriously enough that they instituted a minimum height requirement for admission to the business school. That was easily my favorite ridiculous higher ed story of the year—just completely ludicrous.

There were others, too. Just the other day I saw a job posting at a university in China where credential inflation has gotten so bad that the director of the canteen position required a doctorate. That one stood out. And yet, people say there’s no unemployment problem in China…

Now, in terms of more serious or long-term developments, one story that really caught my attention is about Cintana. They’re using an Arizona State University–approved curriculum and opening franchises across Asia. They’ve had some real success recently in Pakistan and Central Asia, and they’re now moving into South Asia as well.

If that model takes off, it could significantly shape how countries in those regions expand access to higher education. That’s definitely one to watch.

And of course, there’s the gradual integration of AI into universities—which is having all sorts of different effects. Those aren’t headline-grabbing curiosities like the Vietnam height requirement, but they’re the developments we’ll still be talking about in a few years.

TM: That leads perfectly into my last question for you. What’s one trend or change we should be watching in the 2025–26 academic year? One globally, and one locally?

AU: Globally, it’s always going to come back to the fact that nobody wants to pay for higher education. That’s the obvious answer.

And I don’t mean that people in theory don’t want to support higher ed. It’s just that the actual amount required to run higher education systems at their current scale and quality is more than governments or individuals are willing to pay—through taxes or tuition.

So I think in much of the Northern Hemisphere, you’re going to see governments asking: How do we make higher education cheaper? How do we make it leaner? How do we make it less staff-intensive? Not everyone’s going to like those conversations, but that’s going to be the dominant trend in many places.

Not everywhere—Germany’s finances are still okay—but broadly, we’re heading into a global recession. Trump’s policies are playing a role in triggering that downturn. So even in countries where governments are willing to support higher education, they may not be able to.

That means we’re going to see more cuts across the board. And for countries like Kenya and Nigeria—where demand continues to grow but capacity can’t keep up—it’s not going to get any easier.

Unfortunately, a lot of the conversation next year will be about how to make ends meet.

And then there’s what I call the “Moneyball” question in American science. U.S. science—particularly through agencies like NIH and NSF—has been the motor of global innovation. And with the huge cuts now underway, the whole world—not just the U.S.—stands to lose.

In Moneyball, there’s that moment where Brad Pitt’s character says, “You keep saying we’re trying to replace Isringhausen. We can’t replace Isringhausen. But maybe we can recreate him statistically in the aggregate.”

That’s the mindset we need. If all the stuff that was going to be done through NIH and NSF can’t happen anymore, we need to ask: How can we recreate that collective innovation engine in the abstract? Across Horizon Europe, Canada’s granting councils, the Australian Research Council, Japan—everyone. How do we come together and keep global science moving?

That, I think, could be the most interesting story of the year—if people have the imagination to make it happen.

TM: Alex, thanks for joining us today.

AU: Thanks—I like being on this side. So much less work on this side of the microphone. Appreciate it.

TM: And that’s it from us. Thank you to our co-producer, Sam Pufek, to Alex Usher, our host, and to you, our listeners, for joining us week after week. Next year, we won’t be back with video, but we will be in your inboxes and podcast feeds every week. Over the summer, feel free to reach out with topic ideas at [email protected]—and we’ll see you in September.

*This podcast transcript was generated using an AI transcription service with limited editing. Please forgive any errors made through this service. Please note, the views and opinions expressed in each episode are those of the individual contributors, and do not necessarily reflect those of the podcast host and team, or our sponsors.

This episode is sponsored by KnowMeQ. ArchieCPL is the first AI-enabled tool that massively streamlines credit for prior learning evaluation. Toronto based KnowMeQ makes ethical AI tools that boost and bottom line, achieving new efficiencies in higher ed and workforce upskilling.