Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

The nation’s historically Black colleges and universities, known as HBCUs, are wondering how to survive in an uncertain and contentious educational climate as the Trump administration downsizes the scope and purpose of the U.S. Department of Education — while cutting away at federal funding for higher education.

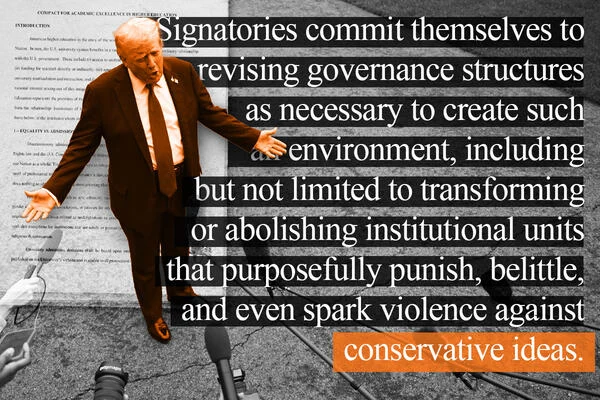

In January, President Donald Trump signed an executive order pausing federal grants and loans, alarming HBCUs, where most students rely on Pell Grants or federal aid. The order was later rescinded, but ongoing cuts leave key support systems in political limbo, said Denise Smith, deputy director of higher education policy and a senior fellow at The Century Foundation, a left-leaning think tank.

Leaders worry about Trump’s rollback of the Justice40 Initiative, a climate change program that relied on HBCUs to tackle environmental justice issues, she said. And there’s uncertainty around programs such as federal work-study and TRIO, which provides college access services to disadvantaged students.

“People are being mum because we’re starting to see a chilling effect,” Smith said. “There’s real fear that resources could be lost at any moment — even the ones schools already know they need to survive.”

Most students at HBCUs rely on Pell Grants or other federal aid, and a fifth of Black college graduates matriculate from HBCUs. Other minority-serving institutions, known as MSIs, that focus on Hispanic and American Indian populations also heavily depend on federal aid.

“It’s still unclear what these cuts will mean for HBCUs and MSIs, even though they’re supposedly protected,” Smith said.

States may be unlikely to make up any potential federal funding cuts to their public HBCUs. And the schools already have been underfunded by states compared with predominantly white schools.

Congress created public, land-grant universities under the Morrill Act of 1862 to serve the country’s agricultural and industrial industries, providing 10 million acres taken from tribes and offering it for public universities such as Auburn and the University of Georgia. But Black students were excluded.

The 1890 Morrill Act required states to either integrate or establish separate land-grant institutions for Black students — leading to the creation of many HBCUs. These schools have since faced chronic underfunding compared with their majority-white counterparts.

‘None of them are equitable’

In 2020, the average endowment of white land-grant universities was $1.9 billion, compared with just $34 million for HBCUs, according to Forbes.

There are other HBCUs that don’t stem from the 1890 law, including well-known private schools such as Fisk University, Howard University, Morehouse College and Spelman College. But more than three-fourths of HBCU students attend public universities, meaning state lawmakers play a significant role in their funding and oversight.

Marybeth Gasman, an endowed chair in education and a distinguished professor at Rutgers University, isn’t impressed by what states have done for HBCUs and other minority-serving institutions so far. She said she isn’t sure there is a state model that can bridge the massive funding inequities for these institutions, even in states better known for their support.

“I don’t think North Carolina or Maryland have done a particularly good job at the state level. Nor have any of the other states. Students at HBCUs are funded at roughly 50-60% of what students at [predominately white institutions] are funded. That’s not right,” said Gasman.

“Most of the bipartisan support has come from the U.S. Congress and is the result of important work by HBCUs and affiliated organizations. I don’t know of a state model that works well, as none of them are equitable.”

Under federal law, states that accept federal land-grant funding are required to match every dollar with state funds.

But in 2023, the Biden administration sent letters to 16 governors warning them that their public Black land-grant institutions had been underfunded by more than $12 billion over three decades.

Tennessee State University alone had a $2.1 billion gap with the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

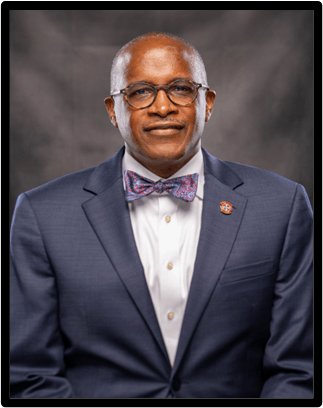

At a February meeting hosted by the Tennessee Black Caucus of State Legislators, Tennessee State interim President Dwayne Tucker said the school is focused on asking lawmakers this year for money to keep the school running.

Otherwise, Tucker said at the time, the institution could run out of cash around April or May.

“That’s real money. That’s the money we should work on,” Tucker said, according to a video of the forum.

In some states, lawsuits to recoup long-standing underfunding have been one course of action.

In Maryland, a landmark $577 million legal settlement was reached in 2021 to address decades of underfunding at four public HBCUs.

In Georgia, three HBCU students sued the state in 2023 for underfunding of three HBCUs.

In Tennessee, a recent state report found Tennessee State University has been shortchanged roughly $150 million to $544 million over the past 100 years.

But Tucker said he thinks filing a lawsuit doesn’t make much sense for Tennessee State.

“There’s no account payable set up with the state of Tennessee to pay us $2.1 billion,” Tucker said at the February forum. “And if we want to make a conclusion about whether [that money] is real or not … you’re going to have to sue the state of Tennessee, and I don’t think that makes a whole lot of sense.”

Economic anchors

There are 102 HBCUs across 19 states, Washington, D.C., and the U.S. Virgin Islands, though a large number of HBCUs are concentrated in the South.

Alabama has the most, with 14, and Pennsylvania has the farthest north HBCU.

Beyond education, HBCUs contribute roughly $15 billion annually to their local economies, generate more than 134,000 jobs and create $46.8 billion in career earnings, proving themselves to be economic anchors in under-resourced regions.

Homecoming events at HBCUs significantly bolster local economies, local studies show. North Carolina Central University’s homecoming contributes approximately $2.5 million to Durham’s economy annually.

Similarly, Hampton University’s 2024 homecoming was projected to inject around $3 million into the City of Hampton and the coastal Virginia region, spurred by increased visitor spending and retail sales. In Tallahassee, Florida A&M University’s 2024 homecoming week in October generated about $5.1 million from Sunday to Thursday.

Their significance is especially pronounced in Southern states — such as North Carolina, where HBCUs account for just 16% of four-year schools but serve 45% of the state’s Black undergraduate population.

Smith has been encouraged by what she’s seen in states such as Maryland, North Carolina and Tennessee, which have a combined 20 HBCUs among them. Lawmakers have taken piecemeal steps to expand support for HBCUs through policy and funding, she noted.

Tennessee became the first state in 2018 to appoint a full-time statewide higher education official dedicated to HBCU success for institutions such as Fisk and Tennessee State. Meanwhile, North Carolina launched a bipartisan, bicameral HBCU Caucus in 2023 to advocate for its 10 HBCUs, known as the NC10, and spotlight their $1.7 billion annual economic impact.

“We created a bipartisan HBCU caucus because we needed people in both parties to understand these institutions’ importance. If you represent a district with an HBCU, you should be connected to it,” said North Carolina Democratic Sen. Gladys Robinson, an alum of private HBCU Bennett College and state HBCU North Carolina A&T State University.

“It took constant education — getting folks to come and see, talk about what was going on,” she recalled. “It’s like beating the drum constantly until you finally hear the beat.”

For Robinson, advocacy for HBCUs can be a tough task, especially when fellow lawmakers aren’t aware of the stories of these institutions. North Carolina A&T was among the 1890 land-grant universities historically undermatched in federal agricultural and extension funding.

The NC Promise Tuition Plan, launched in 2018, reduced in-state tuition to $500 per semester and out-of-state tuition to $2,500 per semester at a handful of schools that now include HBCUs Elizabeth City State University and Fayetteville State University; Western Carolina University, a Hispanic-serving institution; and UNC at Pembroke, founded in 1887 to serve American Indians.

Through conversations on the floor of the General Assembly, and with lawmakers on both sides of the aisle, Robinson advocated to ensure Elizabeth City State — a struggling HBCU — was included, which helped revive enrollment and public investment.

“I’m hopeful because we’ve been here before,” Robinson said in an interview.

“These institutions were built out of churches and land by people who had nothing, just so we could be educated,” Robinson said. “We have people in powerful positions across the country. We have to use our strength and our voices. Alumni must step up.

“It’s tough, but not undoable.”

Meanwhile, other states are working to recognize certain colleges that offer significant support to Black college students. California last year passed a law creating a Black-serving Institution designation, the first such title in the country. Schools must have programs focused on Black achievement, retention and graduation rates, along with a five-year plan to improve them. Sacramento State is among the first receiving the designation.

And this session, California state Assemblymember Mike Gipson, a Democrat, introduced legislation that proposes a $75 million grant program to support Black and underserved students over five years through the Designation of California Black-Serving Institutions Grant Program. The bill was most recently referred to the Assembly’s appropriations committee.

Stateline is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Stateline maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Scott S. Greenberger for questions: [email protected].

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter