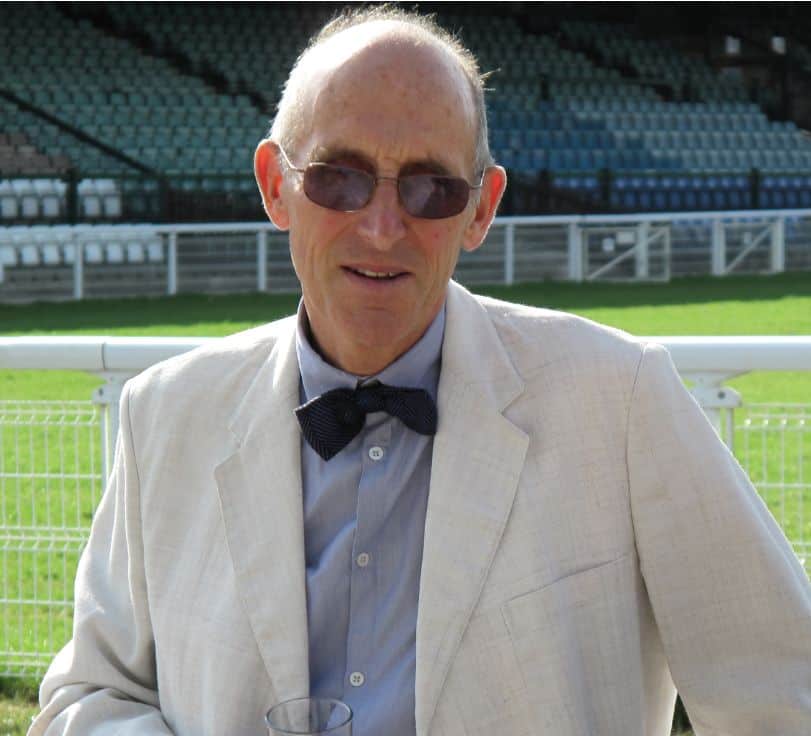

A rigorous mind, an uncompromising integrity, and a lasting legacy in higher education analysis.

John Thompson, who has died after a distinguished career in higher education analysis and public policy, was one of the most intellectually rigorous and ethically uncompromising analysts of his generation. His work fundamentally changed how we understand educational progression, social disadvantage, and widening participation, and it continues to shape policy long after his formal retirement.

John was born on the Wirral and grew up in circumstances that gave him early insight into inequality. His father died when John was young, and he was brought up by a single parent. Exceptionally for his background and environment, he went on to university, studying chemistry at the University of Leicester, where he graduated with a first-class degree. He remained at Leicester to complete a PhD, winning a prize for the most innovative research of his year – an early indication of the originality and methodological seriousness that would mark his later work.

After university, John began his professional life as a teacher in a further education college in Liverpool. He taught boys from highly deprived backgrounds, many of whom had little interest in the subject matter or in formal education at all. The experience made a deep and lasting impression on him. Typically, despite his outstanding academic achievements in Chemistry, he considered himself unqualified to teach Mathematics and went on to achieve a first-class degree in Mathematics with the Open University.

During this period, he joined the Communist Party – an affiliation he did not maintain – but the underlying conviction that injustice must be confronted never left him and became a defining feature of both his personal and professional life.

John later moved from teaching into analytical work, joining the Inland Revenue as an analyst. While working there, he took yet another degree, completing a Master’s in Operations Research. His experience as an analyst at the Inland Revenue led to a position at GE in its direct marketing department – a role that may not have sat comfortably with his political worldview, but which proved unexpectedly formative. The work gave him a sophisticated understanding of population segmentation and data-driven identification techniques, skills that would later underpin his most influential contributions to education policy, including the the POLAR classification (for identifying disadvantaged students, developed under his guidance by one of his proteges in the course of a PhD.

Outside work, John was a passionate and formidable cyclist. He cycled everywhere and at one point held the British record for the 100-mile tricycle time trial, recording the fastest time ever achieved in the UK under the auspices of the Road Time Trials Council (RTTC). With his partner Maggie, he shared a tandem bicycle on which they undertook many long and short journeys together, including cycling holidays at home and abroad. Cycling was not merely a pastime for John; it reflected the discipline, endurance, and quiet determination that characterised so much of his life.

It was in the late-1990s that John undertook the work for which he is probably best known: his research into “who does best at university”. At the time, there was a widely accepted belief that school attainment bore little relationship to performance in higher education. An influential article in the Daily Telegraph even claimed that “A-levels are only slightly better than tossing a coin as a way of predicting who will do well at university”, attributing this conclusion to research by Professor Dylan Wiliam.

John did what he always did: he went back to the sources. Tracing the citations carefully, and then the citations within those citations, he found that no such conclusion was supported by the original research. This episode crystallised another of his enduring frustrations: academics and commentators who cited research they had never actually read.

Continuing his work, John demonstrated a clear – almost linear – relationship between school attainment and subsequent degree outcomes. More controversially, he showed that students from independent schools performed less well at university than their peers from comprehensive schools who had achieved the same A-level grades. The findings were strongly challenged by the independent schools lobby and were ultimately referred to the Royal Statistical Society. After reviewing the analysis, the Society judged it to be the most robust analysis ever encountered on the topic.

Although “who does best at university” brought John wide recognition, it rested on a deeper and even more innovative achievement: his pioneering work on linking administrative records from different sources. John was instrumental in making it possible to link individual school records with university records, and later with Inland Revenue data in the context of student finance and loan repayment. Before this work, analysis relied almost entirely on aggregate data, separately collected across schools, universities, and further education colleges. As a result of John’s work, debates about widening participation, student fees, and social mobility could be informed by robust analysis and evidence rather than spurious correlation and conjecture, allowing far more nuanced and effective policymaking.

Those who worked closely with John will remember two qualities above all others: his honesty and his rigour.

His honesty meant that he would stand by what he knew to be true, even when it was personally risky to do so. Early in his time at HEFCE, a newly appointed Chief Executive had promised the Open University an increase in funding, justifying this internally on the grounds that the cost of teaching an Open University student was similar to that of a conventional undergraduate. John knew this was not correct and had the evidence to prove it. Despite intense pressure to produce analysis that would support the Chief Executive’s commitment, John refused. A stand-off followed, but John would not compromise. In the end, he prevailed – and in doing so earned the lasting respect of the very person he had challenged.

His rigour was equally legendary, and at times exasperating to colleagues. He would not permit conclusions to be stated unless they were fully supported by evidence, and he was deeply resistant to claims of causality that could not be definitively established. On more than one occasion, he prevented colleagues from stating conclusions that seemed obvious from the data but could not be proven to the standard he required. It was not always convenient – but it was always right.

While at HEFCE, John also took great care with the development of others. He sponsored and mentored several junior colleagues through doctoral study, including work that enabled record linkage. These were, in many respects, golden years for HEFCE’s analytical services. Under the leadership of Shekhar Nandy, the unit produced some of the most sophisticated data-driven higher education research in the country and attracted exceptionally talented young statisticians, many of whom stayed on to form the core of the team in subsequent years, and to refine and develop the strands of research that John had initiated.

After retiring from HEFCE, John continued to work on a number of projects for HEPI. Among these was what may have been the first comprehensive analysis demonstrating the consistently poorer educational performance of boys and young men compared with girls and young women at every stage of the education system. The work was generally well received, although it attracted some idiosyncratic criticism – most memorably from a professor of gender studies who diagnosed ‘castration anxiety’ in the analysis. That suggestion caused great amusement among those who knew John well enough to understand that he was ruthlessly objective and entirely without personal agenda.

In 2010, again for HEPI, John analysed the White Paper that preceded the introduction of full-cost student fees. He showed that the proposed system rested on flawed assumptions and would almost certainly cost as much as the more benign regime it was replacing. The Minister for Higher Education at the time, David Willetts, dismissed the HEPI analysis in the House of Commons as ‘eccentric’, only to concede a year later before the Commons Select Committee that it had been “right, but for the wrong reasons”!

John Thompson was a gifted child who overcame the constraints of his background, an analyst of exceptional intellectual honesty, and a colleague whose standards improved everyone around him. He is survived by his partner of many years, Maggie, and by her daughters, Lucy and Clare.

Those of us who worked with John at HEFCE and later at HEPI benefited not only from his work but also from his demeanour and principled behaviour. His legacy lies not only in the methods he developed and the conclusions he established, but in the example he set: that evidence matters, that integrity is non-negotiable, and that intellectual courage is worth the cost.

John’s funeral will be at 10 am on 29th December at WOODLAND CHAPEL, WESTERLEIGH CREMATORIUM, WESTERLEIGH ROAD, WESTERLEIGH, BRISTOL BS37 8RF. All who knew John are welcome, but please RSVP to Bahram Bekhradnia at [email protected]