Morning all.

It’s been a busy summer at HESA Towers. We’ve been developing Boardwise, our new suite of governance products with our partners at Balsam Advisory, and exploring new ideas on data governance and analytics with our friends at Plaid Analytics. We’ve also been touring the country with the Royal Bank of Canada (RBC) Thought Leadership Office and the Business + Higher Education Roundtable (BHER) to talk about higher education, economic growth and productivity. The “what we heard” document from those sessions will be out in mid-September, and there are several follow-up events scheduled, including a leaders’ summit hosted by RBC later this month. This event will focus mainly on how higher education and business can work together to tackle some of the country’s most pressing challenges, such as clean energy and technology, artificial intelligence, and defence. Further insights from this work will also be explored at the BHER Executive Summit in February 2026.

And, of course, our own Re: University conference – where we will be presenting some of the most interesting ideas out there to improve and inspire the quality, effectiveness and experience of postsecondary education in Canada – is coming up in late January in Ottawa. (Tickets are going fast – reserve your spot!)

A couple of other small programming notes:

- The State of Post-Secondary Education in Canada 2025 will be released tomorrow.

- The World of Higher Educationpodcast will still come out every Thursday, but we’re back to an audio-only format because editing is a hassle and apparently very few of you are videophiles.

- The Fifteen will continue to bring you the top global higher education stories every other week.

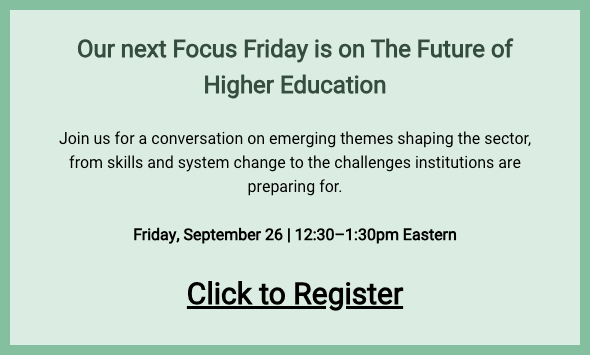

- Next Friday will mark the debut of a new biweekly webinar series, Friday Focus, to be hosted by Tiffany MacLennan, surfacing the most interesting shifts and innovations in Canadian higher education – from AI & technology, cutting-edge programming, and the everchanging student experience – through the voices of those leading the change. We hope you can join us.

- Our University Vice Presidents Network (UVPN) is going strong and is scheduled to convene in Victoria in November, Quebec City in February, and then internationally for a May 2026 Study Tour in Germany.

- Finally, we are targeting the first week of December for the launch of the World of Higher Education Annual Review 2025, a new year-in-review publication which tries to document the year’s shifts across the whole of our crazy sector, right around the globe, using statistics, stories and strategic planning documents.

Now, on to the year ahead.

In most places, I think the hard part for colleges is over. 2025-26 isn’t going to be an easy year, by any means, but the big decisions have mostly been made, future directions have been set and the floor on institutional income has either been reached or is in sight.

Universities, on the other hand, are a different story. They have – not everywhere, but in the main – been more hesitant to act. It’s a conservative sector that is resistant to change, be it financial, organizational or cultural. And the financial problems the sector faces – again, not everywhere but in the main – are going to drag on for quite awhile mainly because international student numbers aren’t bouncing back the way they might have (more on that next week) and because an imminent recession is the opposite of helpful when it comes to provincial finances.

So, it’s going to be a tough year ahead. In my mind, I think there are 5 rules for success.

Rule 1 – Act like Universities are a Means to an End, not an End in Themselves. Literally the worst thing universities can say right now is “universities are crucial, give us more money”. It’s an utterly tone-deaf approach, even if you give it an “elbows up” spin. The sector has been saying it for years and it clearly hasn’t worked, so continuing with this approach is the literal definition of insanity. And the reason it doesn’t work is because Canadians (or at least Canadian politicians) simply don’t believe that universities are crucial because they don’t believe that knowledge and science is useful. Rather, they far prefer a Canada where the construction and natural resources industries continue to call the shots (if there is a Deep State in Canada, it is surely comprised of these two sectors and their watercarriers). The case we need to make is not “spend on universities”, it’s “a knowledge-driven Canada is a better Canada”. And more importantly, it’s not a case institutions can make on their own – they need to make it with lots of other actors, particularly from industry. Alliances, people. Form alliances. Downsize your government relations team, build up your community relations efforts.

Rule 2 – Stop with the Tri-Council Fundamentalism. Federal budgets for research are going to get hammered in the coming months. This will make a lot of people argue that we should ditch all research funds except the tri-councils because inquiry-driven research is sacred etc. I understand the instinct here because so many institutions make council success a key part of the tenure/promotion process. But it’s a bad instinct. No one in Ottawa cares about your tenure processes. You can argue all you want about how basic research is more cost-efficient in terms of driving long-term discovery, but i) the public likes some short-term wins mixed in with the long-term ones and b) nobody outside universities is buying that one story about NSERC funding Geoffrey Hinton’s AI research 30 year ago as a business case for science. Like, nobody. Get over it. Understand that if there is to be growth in Canadian research funding in future, it’s going to look a lot more like Horizon Europe or the Biden Administration’s Chips and Science Act, both of which were widely hailed as being good for science despite – or perhaps because – they are largely mission-driven rather than inquiry-driven. If this is the hill the community chooses to die on, God help us all.

Rule 3 – Focus on what you can control, not what you can’t. Yes, things are bad. You can spend time complaining about it – government is short-sighted, we’re always getting shafted by the granting councils, etc. – or you can get busy. Fire up your friend-raising and fund-raising. Ramp up your spend/effort on international recruitment (more on this next week). Make a big bang with some new programs that stand out. Go big on one theme. Stand out. Please.

Rule 4 – Faster Collegiality is a Must. Part of regaining public confidence is going to involve being able to make changes at the institutional level with much more speed and determination than is historically the case. That means being able to deliver on promises and priority in the immediate term, not in some far-off future, to be able to act as an institution and not just as a sack full of cats fighting over research priorities and teaching schedules. The way this normally happens is to concentrate power in the hands of the upper administration. This is how it works in most of Asia, most of the United States, and increasingly in Europe as well (though crucially, senior admin tends to be elected in Europe). But it doesn’t have to be like that. There’s no obvious reason why collegial governance needs to be slow: it’s just custom and practice. I’ve been saying for a while that better, faster governance is key to institutions in rough times and while too few have heeded that advice, it’s never too late to start.

Rule 5 – Do less, but do it better. Universities are ridiculously strung out. Many forces are at work here, but I will single out two. At a system level, we have governance systems that are great at approving new programs and initiatives but absolutely rotten at pruning them once they have outlived their purpose. Result: institutions do too much, but do it badly, thus leading to enshittifcation. But it works at the level of individual faculty too, since departments tend to hire the biggest keeners in the system, the kind of people who won’t say no to more research, or extra teaching, or whatever. Result: burnout. In a normal organization, a manager would come along and try to make workloads manageable. But since Canadian academia long ago decided that the main purpose of department chairs is to protect staff from unwanted Decanal or Provostial schemes rather than to manage academics’ workloads, there is no one in the system who can actually make the problem go away (high-sounding talk about “wellness” doesn’t do the trick either). So, seriously, do less.

It’s going to be a hard year (or let’s face it, a hard few years), but if everyone gets the basics right, we can come out of this better and stronger.

Good luck everyone. Back to work!