So. This is the last blog of the academic year. Service resumes Tuesday, 2 September.

It’s been a long year. I’m pretty tired. How about you?

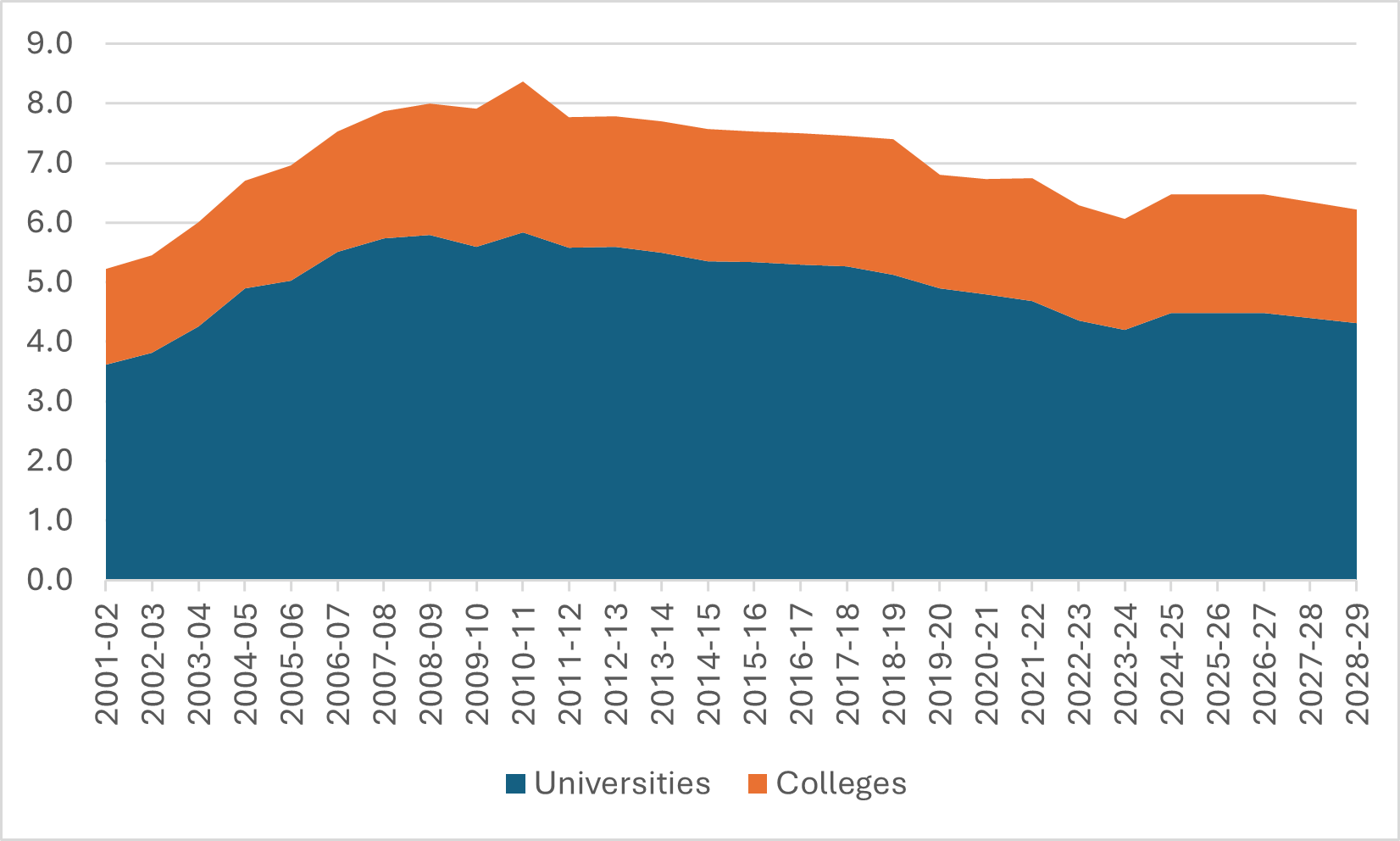

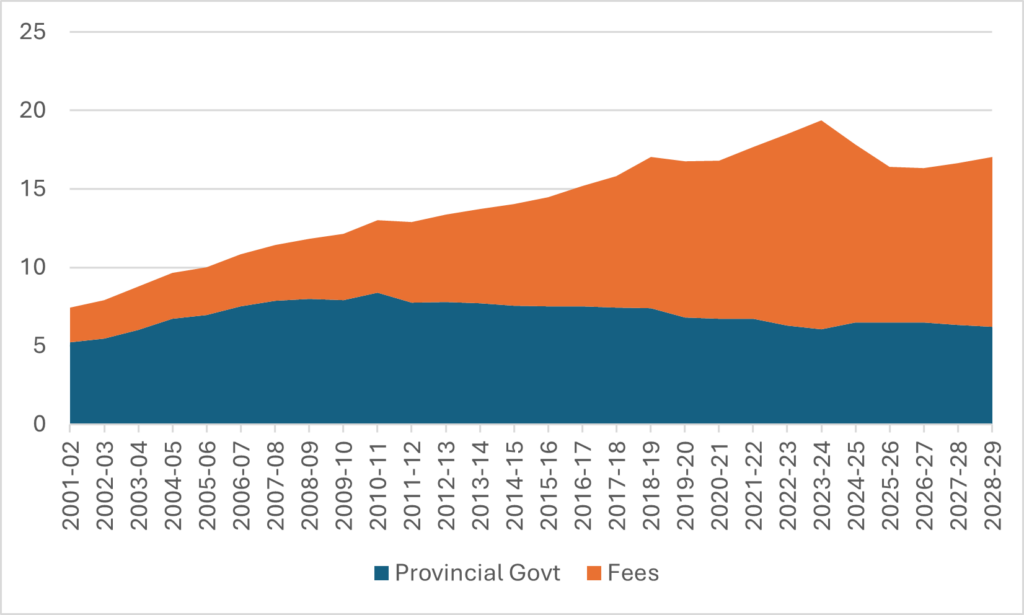

This was the year it all kind of came crashing down: not just here in Canda, but everywhere else too. It’s too long to go through and my more faithful readers already know the story. It’s not just in Canada. In France, Australia, and the UK, we saw institutions having similar problems: all these fantastic higher education institutions we’ve collectively built and, quite simply, nobody wants to pay for it. Not through public funds, not through private fees. Nobody wants to pay for it.

And then there’s American higher education would probably be going through something similar this year, only a greater catastrophe arrived first. I’ll pass over this in silence.

Here in Canada, the sector is increasingly friendless. Parents and students seem less convinced that universities in particular represent good value. And governments are simply indifferent, not because they dislike universities necessarily, but because they dislike or distrust the knowledge economy universities are built to serve.

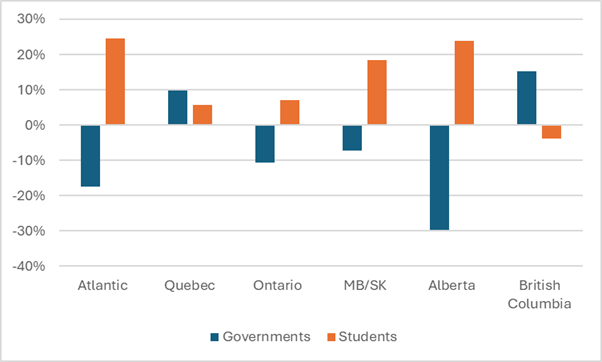

Unfortunately, I think it is going to get worse. Not a single government in Canada released a budget this year which took into account the effects of US tariffs. The result? Allegedly healthy federal and provincial balance sheets are going to get pounded this year and next (and the especially unhealthy ones — BC and Quebec in particular — are going to be especially ugly). Deficits as far as they eye can see. As the saying goes, no one is coming to save us.

I have no doubt that community colleges will find ways to get through this, because they have so far through this crisis mostly shown themselves to have the ability to do what it takes to right the ship. They might not look too good after another round or two of cuts, and it’s not impossible that a few rural colleges might disappear or shrink radically because what they get from governments and domestic tuition fees just isn’t enough to properly serve their communities, but on the whole, I think they will be ok.

Universities, on the other hand. Well, that’s a different story.

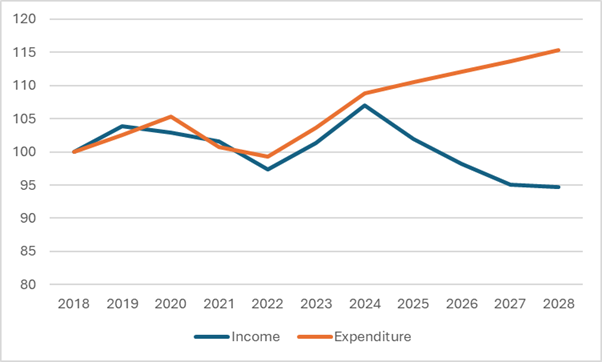

About a year ago, I said that the biggest change universities were going to have to undergo in this new financial age was shifting from a belief that every problem had a revenue-side solution to one in which every problem has a cost-side solution. Institutions can no longer solve their short-term problems by just recruiting another hundred international students. They actually have to change the way they do business. They have to change processes. They have to think about production functions and work processes in a way they haven’t before. And they have to do it while trying to pivot to new missions that give them more traction with government and the public.

I am here to say that I don’t think it’s going so well.

The message that “there is no one coming to save us” has, thankfully, penetrated fairly deeply in universities. Maybe not quite everywhere (hello, VIU!), but in most places. But what I am not sure has penetrated quite so deeply is the corollary that actual change is necessary. My (admittedly limited) vantage point on the sector is that:

- I still see universities spending inordinate amounts of time trying to come up with new revenue-based solutions. It’s a habit they have a hard time kicking.

- Universities are deeply resistant to doing more than the bare minimum of restructuring to meet immediate financial needs. The idea that deep structural change might be necessary remains pretty much anathema. This bare minimum approach means that when the next round of government cuts come – due to recession, or national re-armament or whatever – they are just going to have to cut again, and again, and again. There is very little sign of anyone trying to get ahead of the curve to make both big cuts and big investments in new areas that will help them survive the turmoil.

- I still hear, distressingly often, senior people in universities utter the worst seven words in all of higher education: “we just gotta tell our story better”. Universities are reluctant to face the possibility that governments and the mass public don’t love them the way they are and that they may need to actually, you know, change.

We need to stop acting like the research university of today – which in Canada is really only a creature of the 1970s or perhaps 1960s — is eternal. Universities can die, and have done so rather frequently across history. Universities are the product of particular configurations of social and economic forces. And now, at the moment when the western world is basically re-considering the entire post-WWII order, the idea that universities are going to be uniquely immune to change is bananas. Past performance — which I think has been pretty good — is not a guarantee of future safety.

I am not saying here that universities shouldn’t fight for their own corner: they should! Often more vigorously than they currently do (see my piece on Bill 33, or on how they need to gear up for a fight with Bay Street over whether temporary residents will be international students or TFWs). But they can’t do it by digging in on the status quo.

And so, I will end the academic year by repeating something I said a few months ago. To survive this coming period, universities are going to need:

- Ambition. Don’t waste time doing small things.

- Experimentation. The worst possible thing right now is an addiction to “the way we’ve always done things”

- Dissemination. No one institution got us into the mess. No one institution is going to get out of it alone, either. Institutions need to commit to sharing the results of their experimentation.

I know every university in Canada can, if it chooses, commit to those three things. I have faith. And I believe that if they do, our university sector will come out as strong or stronger than any system in the world.

But any institution that chooses not to commit to them…well, I think they are going to have some issues in the next three years. Serious ones.

It’s up to us. Rest up this summer. Re-charge. We’re all going to need it in ‘25–’26.