From New York to Jakarta, the scene is the same: Shelves overflowing with cheap, ultra-processed snacks and sugary drinks have become the new normal for millions of children. As a result, for the first time in history, more children are obese than underweight.

UNICEF’s new Feeding Profit report explains why: Across the globe, cheap and intensely marketed ultra-processed foods dominate what families are able to put on the table, while nutritious options remain out of reach.

Across the world, one in 20 children under five and one in five children and adolescents aged five to 19 are overweight. The number of overweight children and teens in 2000 almost doubled by 2022, with South Asia experiencing an increase of almost 500%. In East Asia, the Pacific, Latin America, the Caribbean, the Middle East and North Africa, the increase was at least 10%.

Ultra-processed foods and beverages, defined as industrially formulated, are composed primarily of chemically-modified substances extracted from foods, together with additives and preservatives to enhance taste, texture and appearance as well as shelf life.

These foods — which are often cheaper, nutrient poor and higher in sugar, unhealthy fats and salt — are now more prevalent than traditional, nutritious foods in children’s diets.

Can we wean ourselves off ultra-processed foods?

Studies show there’s a direct link between eating a lot of ultra-processed foods and an increased risk of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents. Among teens aged 15-19 years, 60% consumed more than one sugary food or beverage during the previous day, 32% consumed a soft drink and 25% consumed more than one salty processed food.

Today, children’s paths to healthy eating are shaped less by personal choice than by the food environments that surround them. Those are the places where and conditions under which people make decisions about what to eat. They connect a person’s daily life with the broader food system around them, and are shaped by physical, political, economic and cultural factors that help determine what foods are available, affordable, appealing and regularly eaten.

Such environments are steering children toward ultra-processed, calorie-dense options, even when healthier foods are available.

Around the world, countries are beginning to push back. In Mexico, where nearly four million children aged 4-10 are obese, the government took a bold step in March 2025. It banned the sale of ultra-processed foods and sugary drinks in schools.

The new rules go beyond restriction: Schools must offer fresh, regional foods such as fruits, vegetables and seeds, promote water as the default beverage, and establish health education programs. The policy also calls for regular health monitoring, mandatory fortification of wheat and corn flours, and more opportunities for physical activity, with penalties for schools that fail to comply.

Taking steps to slim down our diets

In September 2025, Malaysia’s Ministry of Education followed similar steps. It now prohibits 12 categories of ultra-processed foods and drinks in school canteens, from instant noodles and skewered snacks to frozen desserts and candy.

But even as countries rewrite their food policies, millions of families still face difficult choices at the market.

Shauna Downs, associate professor of food policy and public health nutrition at Rutgers University, has seen firsthand how hunger and obesity can coexist within the same communities in her research on informal settlements in Nairobi, Kenya.

“People are able to find nutrient-rich foods, like leafy greens, fruits, and vegetables, and animal-source foods, but they’re often expensive, and what they can get that’s cheaper is things like mandazi [fried dough], which provide energy, and they taste good, but they’re not getting the nutrients they need,” she said.

Families that want to buy the nutrient-rich foods are forced into heartbreaking choices, Downs said.

“So now they’re making a decision between ‘Am I gonna buy this food from the market, which my family needs, or am I gonna pay for my child to go to school?’” she said.

Looking at food environments

By spotlighting the food environment, consumers and researchers alike can move past the tired “eat less, move more” narrative to fight childhood obesity and ask a better question: Why wasn’t the healthy plate the obvious, easy and most affordable choice in the first place?

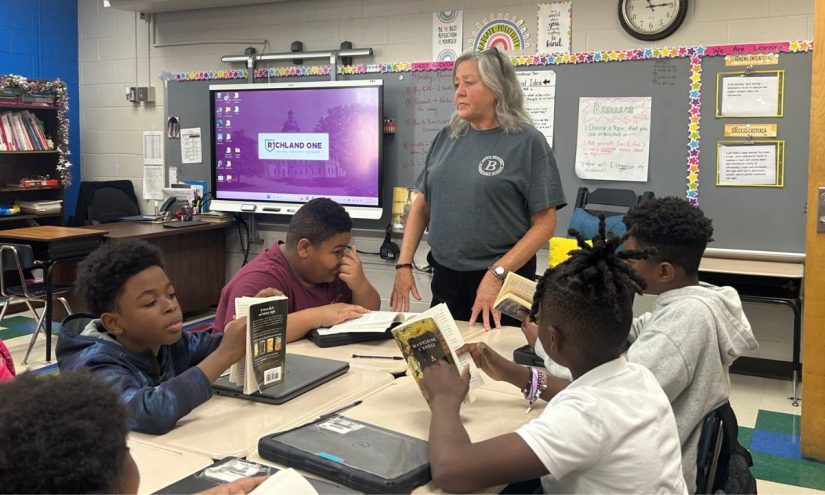

Long before ultra-processed foods flooded grocery shelves, they quietly took over another key part of children’s lives: school cafeterias. Back in 1981, the Reagan administration cut US$1.5 billion in U.S. school food funding, pushing public institutions to rely on convenience over nutrition.

Pamela Koch, associate professor of nutrition and education at Teachers College, Columbia University, said that one of the things cut was for funding for schools upgrade their kitchens.

“That was the same time as the food supply was becoming more and more [saturated] with highly-processed food, and a lot of food companies realized, ‘Wait, we could have a market selling to schools. Schools don’t have money to buy supplies’,” Koch said.

Companies began offering deals: Sign a long-term contract and receive a free convection oven to reheat ultra-processed foods. For schools facing budget cuts and limited staffing, the decision was simple. The cost of that convenience would echo for decades.

Let’s start with school meals.

The nonprofit Global Child Nutrition Foundation, highlights school meals as an essential lever for transforming food systems: Create demand for nutritious foods, improve the livelihoods of those working in the food system and promote climate-smart foods. However, the cost of scaling up national programs depends on the strength of supply chains, underlying food markets, logistics and procurement models.

Countries that depend on imported food, already challenged by infrastructure and expensive trading costs, will face additional challenges in delivering healthy school meals.

In much of the world, climate stress and weak infrastructure are making nutritious food both more difficult to grow and more expensive to purchase.

Small-scale farmers, sheep and cattle farmers, forest keepers and fishers — known collectively as smallholder farmers — grow much of the food in low-income countries. They face worsening yields due to climate change, land degradation and lack of access to the technology and resources that support sustainable food production.

At the same time perishable foods are becoming more expensive because the global supply chain — how food gets shipped from a farm in one country through distribution networks to store shelves in another country — is increasingly threatened by political tension, the lasting effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change.

Durability over nutrition

Kate Schneider, assistant professor of sustainable food systems at Arizona State University, said that smallholder farmers grow food as their livelihood. “They’re not able to grow enough food, which is partly a story of climate change,” Schneider said. “Multiple generations now have been farming … year after year on the same land, but without external inputs –– fertilizers and modern, high-yielding seeds –– they are resulting in very low yields.”

Even when fresh fruits and vegetables are available, logistical barriers make it easier to sell ultra-processed foods. Fresh produce is heavy, vulnerable to spoilage and expensive to move, especially in countries with poor transport networks.

“When we’re thinking about fresh items, they’re perishable, and they need a cold chain,” Schneider said. “You’re paying, when you buy an apple, for the three that also rotted.”

Meanwhile, ultra-processed products like soda avoid this problem entirely: “It’s cheaper for them to have a ton of different bottling plants around countries than to distribute long distances,” Schneider said.

The result of these challenges is a global system that rewards durability over nutrition and continues to make healthy food increasingly out of reach.

Connecting sustainability of diets and the environment

The EAT-Lancet Commission 2.0, a scientific body redefining healthy and sustainable diets, offers a different view: The ultra-processed foods fuelling obesity are also pushing food systems beyond climate and biodiversity limits.

Its newly published report says that nearly half the world’s population can’t afford a healthy diet, while the richest 30% generate more than 70% of food-related environmental damage.

The planetary health diet suggests a plant-rich diet that consists of whole grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts and beans, with only moderate or small amounts of fish, dairy and meat.

To build healthier and more just food systems, experts also recommend a whole list of other things: make nutritious diets more accessible and affordable; protect traditional diets; promote sustainable farming and ecosystems; reduce food waste.

And all of this should be done with the participation of diverse sectors of the society.

The responsibility of transforming food systems falls not only on governments but also on donors and financial partners, development and humanitarian organizations, academic institutions and civil society. The stakes are high, but so is the potential to change. With bold, coordinated action, the next generation of children can be nourished by healthy food, while building food systems that sustain both people and the planet.

Questions to consider:

1. How is obesity connected to the environment?

2. What are some governments doing to try to tackle the obesity crisis?

3. What changes could you make to your diet to make it healthier?