I have been denied tenure at my former R-1 institution. Twice. And after being assured yearly, in writing, that I was making appropriate or exceptional progress toward a positive decision based on departmental criteria and standards. Most of you can imagine, and some of you know, how that felt. The inconsistency seemed misleading and a breakdown of the promotion and tenure process, similar to articles in Inside Higher Ed by Colleen Flaherty and in The Chronicle of Higher Education by Michael W. Kraus, Megan Zahneis and Chelsea Long.

I fought the first decision through formal institutional channels and won, and my institution did a re-review of my dossier from the ground up. In April of this year, I was told that I’d been denied a second time, and I was dismissed at the end of May. However, I could contest the decision processes as a nonemployee. I’m fighting the denial decision (again), and the hearings will begin in the fall.

My area of specialization is program evaluation, with a focus on graduate education. That means I have seen the good, bad and ugly as higher education institutions discuss criteria and standards about student and faculty performance, curriculum and policy; I have a professional and personal interest in all university processes being fair and defensible for all their constituents. My experience is that the processes are not always fair, and having gone through this process before, I have some advice on the steps you should take to fight the decision. While my advice is necessarily grounded in the context of my experience and my former institution’s procedures, it can be adapted to your own.

- Get angry. Talk to your family, friends, colleagues you trust and your dream team of collaborators. Rage about the process and the decision and the decision-makers and the injustice, but get the hot anger out of your system and absolutely do not hurt yourself or anyone else. Let your rage cool so you can use it as energy to fight. You are not powerless, because all university processes and assumptions can be challenged. But know that the odds are heavily stacked against you.

- Recognize the fundamental assumption of institutional competence. There is an assumption that the university correctly followed its policies and procedures and therefore reached a defensible decision. Without very specific performance criteria for promotion, it likely won’t matter how many dozens of works you’ve published, how many grants you’ve supported, how many students you’ve helped complete their degrees, how much your skills are in demand from other units or how you’ve (over-) satisfied the criteria against which you were supposed to be judged. The standing assumption is that the university did its due diligence.

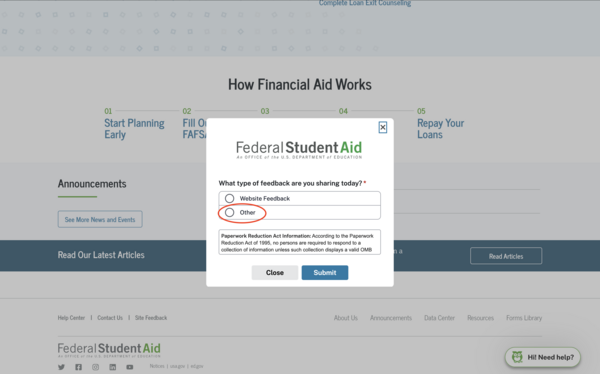

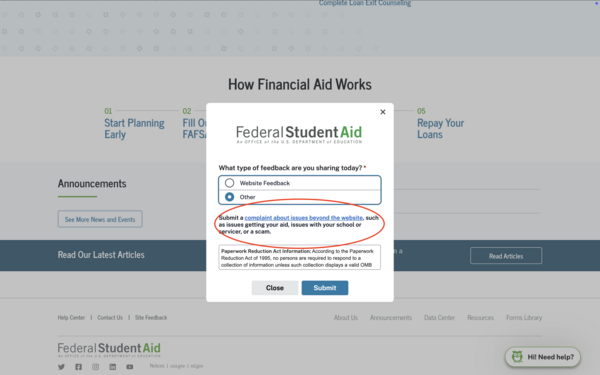

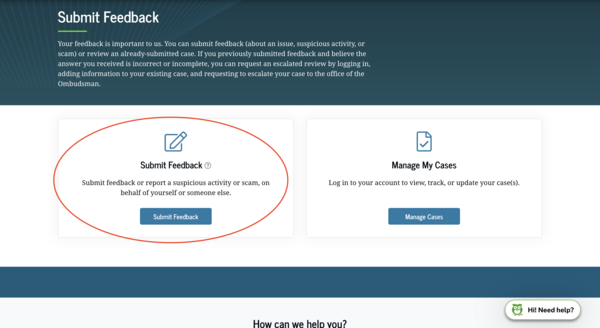

- Get help. Your institution has a vested interest in making sure its processes are defensible and that you can fight against decisions corrupted by inappropriate processes. Ask for a grievance hearing by the university’s regulatory body or a hearing panel (in my former institution, this group is housed in the University Senate). They should be able to connect you with a tenured faculty advocate to help you develop your process-based argument. To prevent further corruption in the process and avoid possibilities of retaliation, this advocate must be housed in a different college from the one in which the decisions were made.

You may have the option of using an external lawyer or union representative to argue your case, but if you bring a lawyer, the respondent will bring one, too. Do what you think is best, but know that the standard of evidence in a grievance hearing is different from that in a court of law, and will likely be closer to “likelihood of procedural issues or prejudicial influence” than to “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

- Be clear about the relief you’re requesting. Even if a grievance panel rules in your favor, they may be limited in the relief they can offer. It’s unlikely that they can simply overturn the provost’s decision, but they may be able to recommend a re-review of your dossier. It may be helpful to think about the worst-case scenario—if your dossier is sent for re-review by the same people who voted against you the first time—and ask for reasonable, specific protections to make the re-review fair and balanced.

Be sure to request that the judgment includes a monitoring and compliance aspect. If the panel rules in your favor, the institution needs to ensure that the recommendations are followed. Don’t let assumptions of institutional competence prevent this from happening, and do not take on that responsibility yourself.

- Use available templates. The grievance panel likely has a template to help you structure your argument. Use it faithfully, and don’t deviate from the specific information it requests. It will likely start by asking you to form the basis of your argument by quoting verbatim from your institution’s tenure code. Copy and paste this to make it easy for the panel to find information when they hear your case. The panel needs to stay within its institutional authority, and you must convince them immediately that your experience and concerns about the process are within their purview.

- Read and re-read your institution’s foundational documents. There are at least three essential documents you must use to support your argument that the process was corrupted: the department or college’s faculty handbook, the regents’ or president’s statement on tenure criteria and ways of contesting decisions, and statements on employee conduct inclusive of reporting requirements for policy violations. You must show how procedural violations significantly contributed to an unjust decision. Examples of such violations could include:

- Discrimination against personal beliefs and expression, or factors protected by federal/state law (e.g., equal opportunity violations, Title IX violations)

- Decision-makers’ dismissal of available information about your performance

- Demonstrable prejudicial mistakes of fact

- Other factors that cause substantial prejudice

- Other violations of university policy

After you have articulated the criteria you are using to contest the decision, you must substantiate each claim with evidence that the violation negatively influenced the final decision. The burden of proof will be on you.

- Organize your evidence. Whatever evidence you present must be organized, accessible and easy for the hearing panel to review. It may be helpful—and therapeutic—to start by making a comprehensive timeline of the pertinent events that led to the decision. Include the dates and written summaries of every annual review, the steps you took to address any human resources issues, the outcomes of those steps, leadership transitions, as well as sociopolitical events that directly influenced the department and institution. Your goal is to share with the panel the entirety of your experience at the institution and make the argument that you did the best you could to address any real or perceived performance issues.

Include the official dossier that was passed through the system as evidence, and use the highlight function of the PDF software to focus on the parts that are most important for your case and that best challenge the assumption of institutional competence. Keep a running list of your documented evidence, which you’ll submit as a set of appendices, and refer to your appendices in the complaint document itself, using quotes cut and pasted directly from your primary sources.

In the document where you set out your complaint, refer to individual appendices by letter, name and page number, so readers can find information and see your evidence in the original context (e.g., “Appendix C: Committee response to factually inaccurate information introduced in faculty discussion, p. 22–24”). Copying and pasting evidence from primary sources will make it easier to reconcile page numbers in the complaint document later. This process is also helpful if you need to argue that the content of the dossier was misrepresented by decision-makers or that one or more particularly vocal individuals are waging a vendetta against you (e.g., “Appendix E: Unsolicited letter from Professor [X] that engages in conspiracy theories about you, p. 100–125”).

It is crucial to make the argument that you were treated unfairly and in violation of university policy, and that your treatment was significantly different from that of your colleagues who were under review at the same time or in the immediate past. If, for example, a decision-maker voted against your promotion because of their individual critiques of your work, and those critiques are not consistent with other levels of review or they attack the credibility of the other reviewers, you have an argument for their idiosyncratic interpretation of the promotion criteria. Put that evidence in an appendix and draw attention to it.

It is also helpful to be able to point to the research of others in your department who used the same scholarly processes but who were not critiqued similarly. This can help you argue differential application of criteria and standards of performance, or that a particular reviewer is applying the standards of research in their discipline to your own, which may be a violation of the tenets of academic freedom (talk to representatives from your institution’s academic freedom committee for more information). This comparison may be essential if you are alleging discrimination or prejudicial treatment that may be based on your personal characteristics.

- Do not fear a request for summary judgment. This processual request means that the respondent in your case (usually a high-level decision-maker such as the provost or dean) is using the assumption of institutional competence to ask that the case be dismissed without a formal hearing. The respondent will argue that everything was done correctly, that the decision was justified and that you are simply angry about the decision. The request will likely be formal and the words intimidating, but that may be the point. Read every word so you can respond in writing to each argument, and prepare responses on the assumption that the issues will come up during oral arguments at the official hearing. Sometimes the request for summary judgment will be peppered with prejudicial language that helps reinforce the basis of your complaint. Use their words against them.

- Prepare your witnesses. You will want to identify good witnesses who will substantiate your main points, but not people who will repeat their evidence from the same perspective; you do not want to bore the hearing panel. Let your witnesses know who your other witnesses are and you can give them a sense of the questions you will ask them during the hearing. You cannot, however, coach them on how to respond; witnesses must be able to respond to your questions honestly, and their responses must stand up under cross-examination.

Be sure to list the respondent and decision-makers on your witness list; you don’t want to miss the chance to hold them accountable for the things they’ve written and the decisions they’ve made. Don’t waste time indicting them on their leadership practices. Instead, show how their active and passive behaviors violated policy and prejudiced the review process in violation of the university’s foundational documents.

- Make the most of the hearing. You may find that the hearing is a very formal process, that an external lawyer will be present for the institution (not the respondent) to ensure the process unfolds correctly and a court transcriptionist will ensure accurate recording of testimony. The witnesses may be sworn in, and you can count on them being asked questions by the complainant, respondent and the hearing panel. If possible, you should lead the questioning for your witnesses and ask your advocate to lead the questioning of the respondent and their powerful witnesses to minimize the power imbalance.

The respondent may not have many questions for you, but remember that you have the burden of proof, and they will not want to provide additional opportunities for you to substantiate your claims. If they do open additional areas of critique, be ready to call out the ones that are inconsistent with policy and processes. Expect to be physically and emotionally exhausted at the end of your hearing.

- Respond to the decision. When the hearing panel’s decision arrives, expect strong emotions. You may feel vindicated and think that you’ve finally been heard or feel as if you’ve been traumatized again. Even if you win, both are fair responses. If you won on all or some of the issues you raised, you can expect the panel to propose a set of recommendations intended to address those issues, but the process is not yet over.

The panel may be empowered only to make recommendations to the university president, who has the final say on what happens. The president has the right to overrule the panel, just as they have the right to order compliance with its recommendations. You can write a formal letter to the president about the panel’s recommendations, as can the respondent. If you have concerns about the recommendations, especially if new issues came to light during the hearing, this is your one chance to make those issues known to the ultimate decision-maker.

Because the grievance hearing may have shown that the process contained problems that have not likely been institutionally addressed, emphasize monitoring and compliance with hope for reconciliation. Don’t expect the president to grant you additional protections beyond what was recommended by the panel, but if the re-review is corrupted, you have documentation showing that you were concerned about making the process fair and transparent and that you did your due diligence.

- Go through the promotion and tenure review process again or leave the institution. Going for tenure again means another year of hoping for a positive decision, dreading a negative one and thinking about your next steps. This is a very difficult time, especially if the underlying issues have not been acknowledged or addressed. Do the best you can, and document everything. A counselor will be essential for processing the ongoing experience.

If your complaint exposed evidence of systematic harassment or prejudicial behavior against you, reach out to the equal opportunity or Title IX offices for support. They have the option of opening formal or informal investigations but may not be likely to do this during a tenure review or re-review because they cannot be seen as influencing the process. They may not be able to act until you have been promoted or have officially lost your job (again), at which point you might wonder why you should reach out. The answer is unsatisfying but simple: You connect with them because you need emotional support and with the hope they can eventually help address the underlying factors that corrupted the process.

If you didn’t win on the redo, you’ll need to find another job somewhere else. I hope you’ve used this last year to network and apply for opportunities as you balanced the burden of the grievance process on top of your regular commitments of teaching, research and service.

If you’re looking at going through this process, you have my sympathy, support and encouragement. Going through it has been one of the hardest experiences of my life, but I’m glad I did it, even if I cannot change my former institution; I can only hope that they will not waste my experience by ignoring the issues it exposed. I couldn’t have done it the first time without extraordinary support from people who hate injustice and fear for institutions that do not follow their own rules. As I prepare for the second round, I will continue to look to my former colleagues for support as I try to be strong for myself, my family, my (former) students and others that go through this process.

Regardless of what the future brings, I did my best to challenge prejudicial and harrowing issues in higher education by opening conversation about them and dragging trauma from the shadows into the light. No matter the ultimate decision, I can walk with my head high.

John M. LaVelle is a scholar of program evaluation specializing in the academic preparation of program evaluators. He lives in the United States with his family and is cautiously optimistic about the future.