When a group of researchers at Northwestern University uncovered evidence of widespread—and growing—research fraud in scientific publishing, editors at some academic journals weren’t exactly rushing to publish the findings.

“Some journals did not even want to send it for review because they didn’t want to call attention to these issues in science, especially in the U.S. right now with the Trump administration’s attacks on science,” said Luís A. Nunes Amaral, an engineering professor at Northwestern and one of the researchers on the project. “But if we don’t, we’ll end up with a corrupt system.”

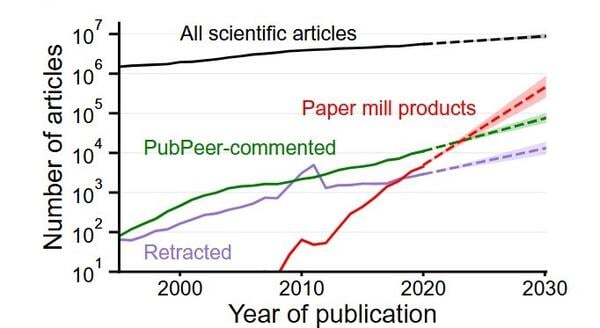

Last week Amaral and his colleagues published their findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. They estimate that they were able to detect anywhere between 1 and 10 percent of fraudulent papers circulating in the literature and that the actual rate of fraud may be 10 to 100 times more. Some subfields, such as those related to the study of microRNA in cancer, have particularly high rates of fraud.

While dishonest scientists may be driven by pressure to publish, their actions have broad implications for the scientific research enterprise.

“Scientists build on each other’s work. Other people are not going to repeat my study. They are going to believe that I was very responsible and careful and that my findings were verified,” Amaral said. “But If I cannot trust anything, I cannot build on others’ work. So, if this trend goes unchecked, science will be ruined and misinformation is going to dominate the literature.”

Luís A. Nunes Amaral

Numerous media outlets, including The New York Times, have already written about the study. And Amaral said he’s heard that some members of the scientific community have reacted by downplaying the findings, which is why he wants to draw as much public attention to the issue of research fraud as possible.

“Sometimes it gets detected, but instead of the matter being publicized, these things can get hidden. The person involved in fraud at one journal may get kicked out of one journal but then goes to do the same thing on another journal,” he said. “We need to take a serious look at ourselves as scientists and the structures under which we work and avoid this kind of corruption. We need to face these problems and tackle them with the seriousness that they deserve.”

Inside Higher Ed interviewed Amaral about how research fraud became such a big problem and what he believes the academic community can do to address it.

(This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Q: It’s no secret that research fraud has been happening to some degree for decades, but what inspired you and your colleagues to investigate the scale of it?

A: The work started about three years ago, and it was something that a few of my co-authors who work in my lab started doing without me. One of them, Jennifer Byrne, had done a study that showed that in some papers there were reports of using chemical reagents that would have made the reported results impossible, so the information had to be incorrect. She recognized that there was fraud going on and it was likely the work of paper mills.

So, she started working with other people in my lab to find other ways to identify fraud at scale that would make it easier to uncover these problematic papers. Then, I wanted to know how big this problem is. With all of the information that my colleagues had already gathered, it was relatively straightforward to plot it out and try to measure the rate at which problematic publications are growing over time.

It’s been an exponential increase. Every one and a half years, the number of paper mill products that have been discovered is doubling. And if you extrapolate these lines into the future, it shows that in the not-so-distant future these kinds of fraudulent papers would be the overwhelming majority within the scientific literature.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America

Q: What are the mechanisms that have allowed—and incentivized—such widespread research fraud?

A: There are paper mills that produce large amounts of fake papers by reusing language and figures in different papers that then get published. There are people who act as brokers between those that create these fake papers, people who are putting their name on the paper and those who ensure that the paper gets published in some journal.

Our paper showed that there are editors—even for legitimate scientific journals—that help to get fraudulent papers through the publishing process. A lot of papers that end up being retracted were handled and accepted by a small number of individuals responsible for allowing this fraud. It’s enough to have just a few editors—around 30 out of thousands—who accept fraudulent papers to create this widespread problem. A lot of those papers were being supplied to these editors by these corrupt paper mill networks. The editors were making money from it, receiving citations to their own papers and getting their own papers accepted by their collaborators. It’s a machine.

Science has become a numbers game, where people are paying more attention to metrics than the actual work. So, if a researcher can appear to be this incredibly productive person that publishes 100 papers a year, edits 100 papers a year and reviews 100 papers a year, academia seems to accept this as natural as opposed to recognizing that there aren’t enough hours in the day to actually do all of these things properly.

If these defectors don’t get detected, they have a huge advantage because they get the benefits of being productive scientists—tenure, prestige and grants—without putting in any of the effort. If the number of defectors starts growing, at some point everybody has to become a defector, because otherwise they are not going to survive.

Q: [Your] paper found a surge in the number of fraudulent research papers produced by paper mills that started around 2010. What are the conditions of the past 15 years that have made this trend possible?

A: There were two things that happened. One of them is that journals started worrying about their presence online. It used to be that people would read physical copies of a journal. But then, only looking at the paper online—and not printing it—became acceptable. The other thing that became acceptable is that instead of subscribing to a journal, researchers can pay to make their article accessible to everyone.

These two trends enabled organizations that were already selling essays to college students or theses to Ph.D. students to start selling papers. They could create their own journals and just post the papers there; fraudulent scientists pay them and the organizations make nice money from that. But then these organizations realized that they could make more money by infiltrating legitimate journals, which is what’s happening now.

It’s hard for legitimate publishers to put an end to it. On the one hand, they want to publish good research to maintain their reputation, but every paper they publish makes them money.

Q: Could the rise of generative AI accelerate research fraud even more?

A: Yes. Generative AI is going to make all of these problems worse. The data we analyzed was before generative AI became a concern. If we repeat this analysis in one year, I would imagine that we’ll see an even greater acceleration of these problematic papers.

With generative AI in the picture, you don’t actually need another person to make fake papers—you can just ask ChatGPT or another large language model. And it will enable many more people to defect from doing actual science.

Q: How can the academic community address this problem?

A: We need collective action to resist this trend. We need to prevent these things from even getting into the system, and we need to punish the people that are contributing to it.

We need to make people accountable for the papers that they claim to be authors of, and if someone is bound to engage in unethical behavior, they should be forbidden from publishing for a period of time commensurate with the seriousness of what they did. We need to enable detection, consequences and implementation of those consequences. Universities, funding agencies and journals should not hide, saying they can’t do anything about this.

This is about demonstrating integrity and honesty and looking at how we are failing with clear eyes and deciding to take action. I’m hoping that the scientific enterprise and scientific stakeholders rise to that challenge.