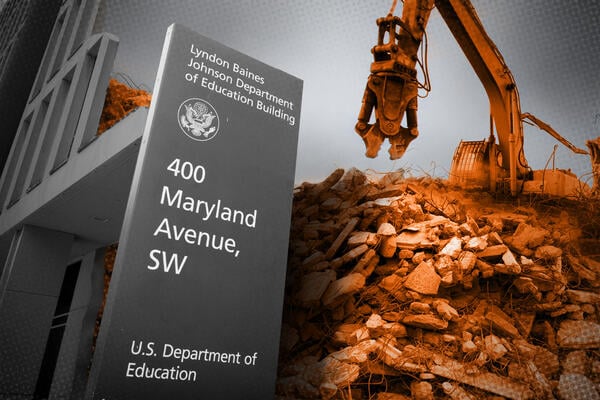

In a recent opinion piece entitled “This Law Made Me Ashamed of My Country,” former Harvard University president and U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Lawrence Summers details the human brutality that will result from the recent unprecedented cuts to Medicaid. One glaring omission in his compelling narrative is concern for the estimated 3.4 million college students who are Medicaid recipients.

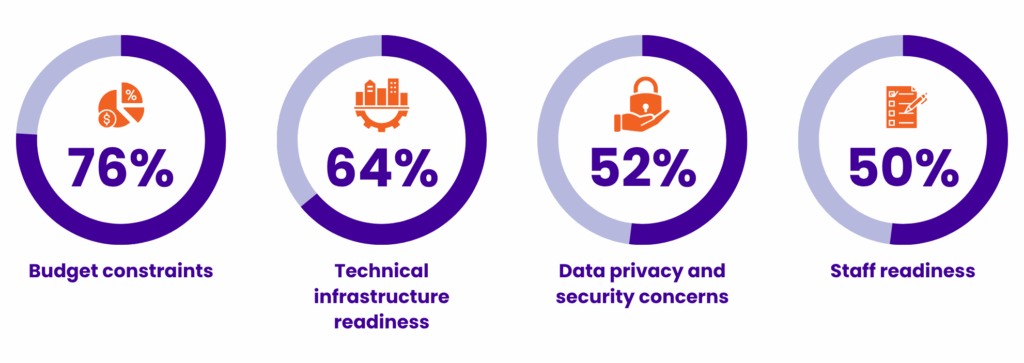

Especially vulnerable are those students with disabilities and chronic conditions, including mental health issues, which recently surpassed financial considerations as the primary reason students are either dropping out of college or not attending in the first place. In addition, when states face budget shortfalls, as they will with the federal Medicaid cuts, higher education is often one of the first areas targeted, leading to higher tuition, fewer resources for students and cuts to academic support services. It is certain that reductions in state-funded appropriations will have a direct negative impact on college access and quality for the approximately 13.5 million students enrolled in America’s community colleges and public universities. The catastrophic repercussions, including the exacerbation of existing healthcare disparities, will be disproportionately felt in rural and underserved communities.

Moreover, both poor health and financial insecurity are known to significantly reduce cognitive bandwidth, impeding the ability of students to learn and resulting in lower completion rates. While racism, sexism, homophobia, ableism and other forms of discrimination each contribute to diminished cognitive bandwidth. studies show that belonging uncertainty is one of the biggest bandwidth stealers. Since the passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, I haven’t been able to stop thinking about the long-term consequences for those who already have doubts about whether they belong in college.

My understanding of the subtle but powerful ways in which policies and practices communicate exclusion is not a mere exercise in moral imagination—it is at the core of my lived experience. When I began college as a first-generation student at the age of 17, I was able to escape the factory work I had done alongside my mother the previous summer only because of funding I received under the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act. At the time, CETA funds were reserved for those at the lowest socioeconomic rungs who were considered at risk of being permanently unemployable. That fall, with the additional help of Pell grants and Perkins loans, I attended a local community college that had just opened in the small, rural town in which I lived. Throughout my first two years in college, I worked 35 hours a week under the CETA contract, took a full course load of five classes a semester, and served as a caregiver to my mother, who was chronically ill. Like my mother, I suffered from severe asthma, during the days before biologics and inhaled corticosteroids were available to manage the disease, and Medicaid was a lifeline for both of us.

One late afternoon, I rushed across town to the pharmacy from my American literature class that was held in the basement of the Congregational church, trying to make it before going to my Bio 101 lab, taught in the public high school after hours. My exchange with the pharmacist was straight out of a Monty Python skit. There were people milling around, browsing the makeup aisle and buying toiletries, but there was no one other than me picking up prescriptions. Yet, when I handed over my Medicaid card, the person controlling access to the medicine yelled, loud enough for everyone to hear, “Title XIX patients line up over there.” Regardless of his intention, the pharmacist’s insistence that I was in the wrong line and that I move to a different, nonexistent line, when in fact I was the only one in any line and he was the only person behind the counter, was more than an exercise in blind adherence to pointless bureaucratic protocol—it was a reinscription of the notion that there are spaces across all sectors of society reserved for those who are wealthier, healthier and more “deserving.” Students who are already uncertain about whether they belong in college begin to internalize the idea that their presence on campus is conditional and tolerated.

When national leaders frame Medicaid as an “entitlement” and abuse of taxpayer money, their rhetoric conveys a sense of stigmatization and the appropriateness of shame felt by those relying on it. And I am especially concerned about the effect of stricter Medicaid work requirements on those in communities like mine, with limited job opportunities and little to no public transportation. The recent cuts to Medicaid send a message to them that their struggles are either invisible or unimportant.

The new Medicaid policies aren’t accidental missteps. They are the result of a social policy ecosystem built to privilege some while sidelining others. Thus, when we see Medicaid cuts and rollbacks in programs such as SNAP (supplemental nutrition assistance program), we need to understand them not just as budgetary decisions, but as deliberate reinforcements of exclusion. Indeed, Medicaid cuts don’t just remove healthcare—they erode the social contract that says everyone is deserving of access to education and well-being. Rather than reaffirming higher education as a cornerstone of the American Dream for students at the lowest socio-economic rungs, the message from cuts to Medicaid is loud and clear: If you are poor, you don’t belong in college. Higher education is reserved for those who don’t need help to get or stay there.

As Jessica Riddell, an American Association of Colleges and Universities board member, reminds us, “The systems in higher education are broken and the systems are working the way they are designed.” For this reason, higher education advocates at all levels must organize, teach and lead in ways that dismantle that design.