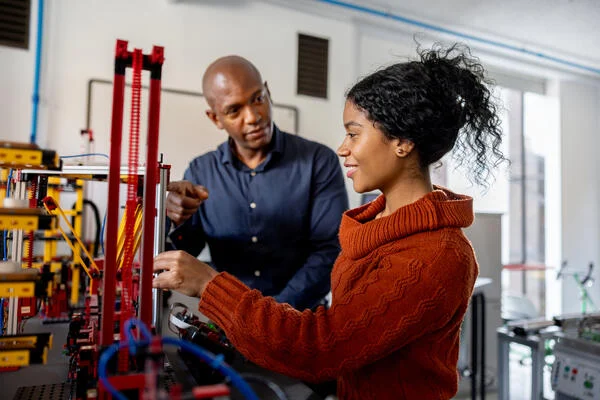

Black students enroll in career and technical education programs at rates on par with their peers, but studies suggest they’re overrepresented in service-oriented fields that lead to lower-wage jobs, and less likely to participate in CTE courses in potentially lucrative STEM fields.

A new research brief, released last week by the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, delved into such inequities and explored possible solutions based on qualitative interviews with Black program staff, current and former CTE students, members of workforce development organizations, training providers, researchers, and other CTE experts. The authors argue those voices are especially critical when federal legislation funding the programs—the Strengthening Career and Technical Education for the 21st Century Act, or Perkins V—is poised for reauthorization in fiscal year 2026.

The report pointed out that in the 2022–23 academic year, Black students made up about 13 percent of high school students and about 15 percent of college students in CTE programs. But a 2020 analysis of CTE data in 40 states by Hechinger Report and the Associated Press found that Black students were less likely than their white peers to enroll in courses focused on science, technology, engineering, math and information technology, and more likely to take classes in fields such as hospitality and human services.

A 2021 report by the Urban Institute also found that compared to their white peers, Black students in CTE courses had significantly lower grade point averages, lower rates of earning credentials or degrees at their first colleges, and a lower likelihood of finding a job in a related field. On average, Black participants in these programs earned more than $8,200 less than white students six years after starting CTE programs, controlling for the highest degree attained and sector of study. Earnings gaps worsened for Black students in online CTE programs; Black students who enrolled in those earned less than half of what their white peers did, despite having started in the same program in the same year, eventually earning the same degrees.

“These disparities are major barriers to increasing the earning potential of Black workers and learners and to narrowing the racial wealth divide,” Joint Center president Dedrick Asante-Muhammad said in a news release.

Lessons Learned

In interviews with the Joint Center, Black CTE experts shared insights into some of the challenges of providing more equitable CTE programs.

Some emphasized that Black CTE teachers, and technical instructors in general, are hard to recruit and retain because they can make better salaries working industry jobs in their fields, leaving students without mentors who look like them. In general, the experts raised concerns about CTE instructors lacking professional development, including on culturally responsive teaching.

The research brief also suggested that Black communities don’t always trust CTE programs because historically, schools funneled Black students into low-quality technical programs. CTE programs hold a stigma for some potential students who still view them as pathways for students of color considered unlikely to attend college rather than a viable career step that doesn’t preclude higher education, the brief said.

Experts also noted that while Perkins V funds require states to submit a local needs assessment, which involves reviewing enrollment and performance data for CTE students, data collection varies across states and gaps in data too often serve students poorly. For example, the mandatory accountability measures for Perkins V funds require data on CTE concentrators—high school students who finished at least two courses in the same CTE program—but that doesn’t include college students or students who dabble in CTE but don’t qualify as a concentrator.

Co-author of the brief and Joint Center workforce policy director Kayla Elliott also acknowledged that the Trump administration’s recent decision to shift management of CTE programs from the Department of Education to the Department of Labor creates new uncertainty for the programs.

“This raises real concerns for the program’s effectiveness and the efficiency of support services for state administrators,” she said in the release. “Some states have already reported waiting months for their Perkins funding with little communication or support from the administration.”

But CTE experts also said Perkins V funding is flexible in ways that can help support Black students. For example, states can use up to 15 percent of the federal funds to drive innovation and implement new programs. States can also combine Perkins V funding with other funding sources, like the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act, which can help states better align CTE programs and workforce development programs. The funds can also be used for career exploration activities to introduce Black students to these programs.

The research brief offered recommendations to improve Black student access and outcomes in CTE, including increasing federal funding during the next reauthorization; improving retention and recruitment strategies for Black CTE teachers, including by raising instructor wages; and enhancing data collection standards. The authors also suggested CTE programs better align with workforce development efforts at the state level and do more engagement and outreach to help Black families better understand how these programs can lead to high-earning technical careers.