There’s a growing tension I’m hearing across higher education marketing and enrollment teams right now: AI is answering students’ questions before they ever reach our websites, and we’re not sure how, or if, we’re part of those answers.

That concern is valid, but the good news is that Answer Engine Optimization (AEO) isn’t some futuristic discipline that requires entirely new teams, tools, or timelines.

In most cases, it’s about getting much more disciplined with the content, structure, and facts you already publish so that AI systems can confidently use your institution as a source of truth.

And with some dedicated time and attention, there’s meaningful progress you can make starting today.

Here are five actions higher ed teams can realistically take right now to improve how they appear in AI-powered search and answer environments.

1. Run a Simple “Answer Audit” to Establish Your Baseline

Before you can improve how you show up in AI-generated answers, you need to understand where you stand today, and that starts with asking the same questions your prospective students are asking.

Identify Real Student Questions

Select five to ten realistic, high-intent student questions, ideally pulled directly from admissions conversations, search query data, or inquiry emails.

Test Visibility Across Major Answer Engines

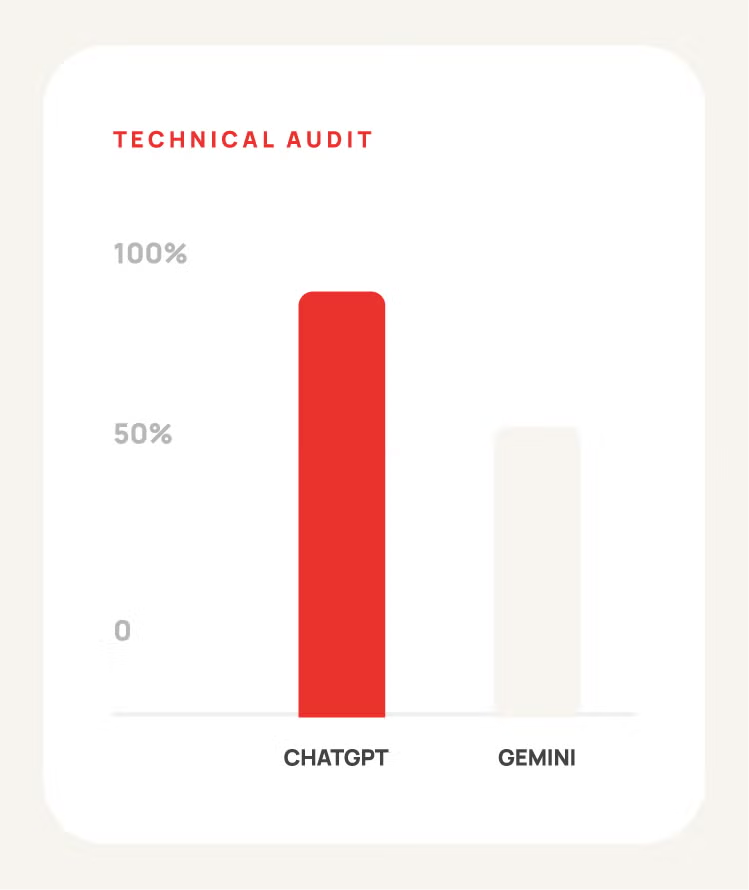

Run those questions through a handful of major answer engines, such as:

- Google AI Mode or AI Overviews

- ChatGPT

- Gemini

- Perplexity

- Bing Copilot or AI Overview search mode

This isn’t a perfect science, as your geography and past search history does affect visibility, but it will give you a quick general idea.

Document What Appears—and What Doesn’t

For each query, document a few critical things:

- Does your institution appear in the answer at all?

- If it does, what information is being shared, and is it accurate?

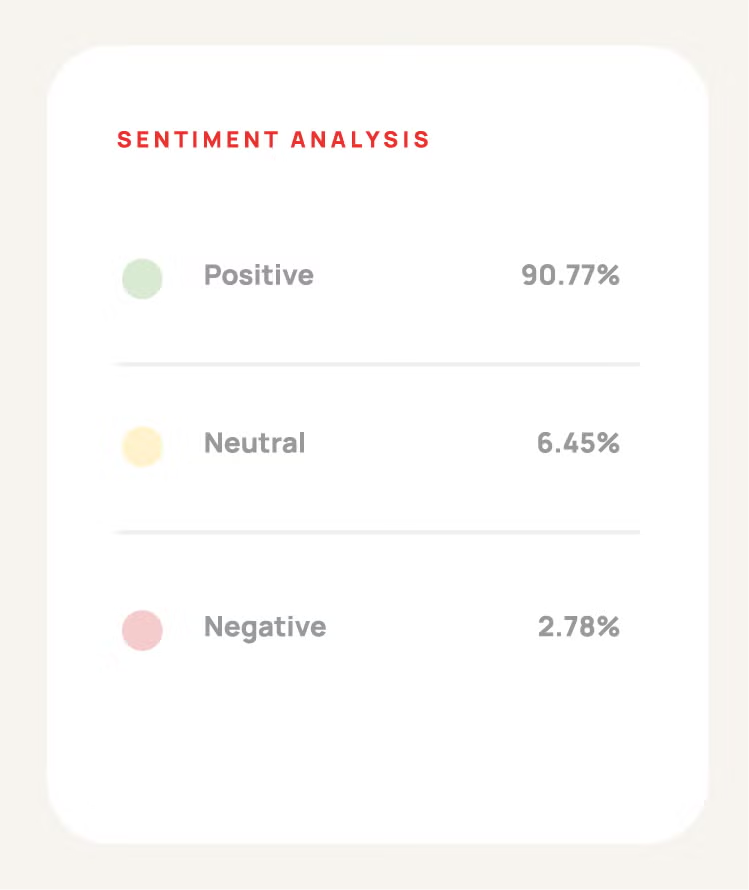

- How is your institution being described? Is the tone neutral, positive, or cautious, and does it align with how you want to be perceived?

- Which sources are cited or clearly influencing the response (your site, rankings, Wikipedia, third-party directories)?

Log this in a simple spreadsheet. What you’ve just created is your initial visibility benchmark, and it’s far more informative than traditional rankings or traffic reports in an AI-first discovery environment.

Where We Can Help

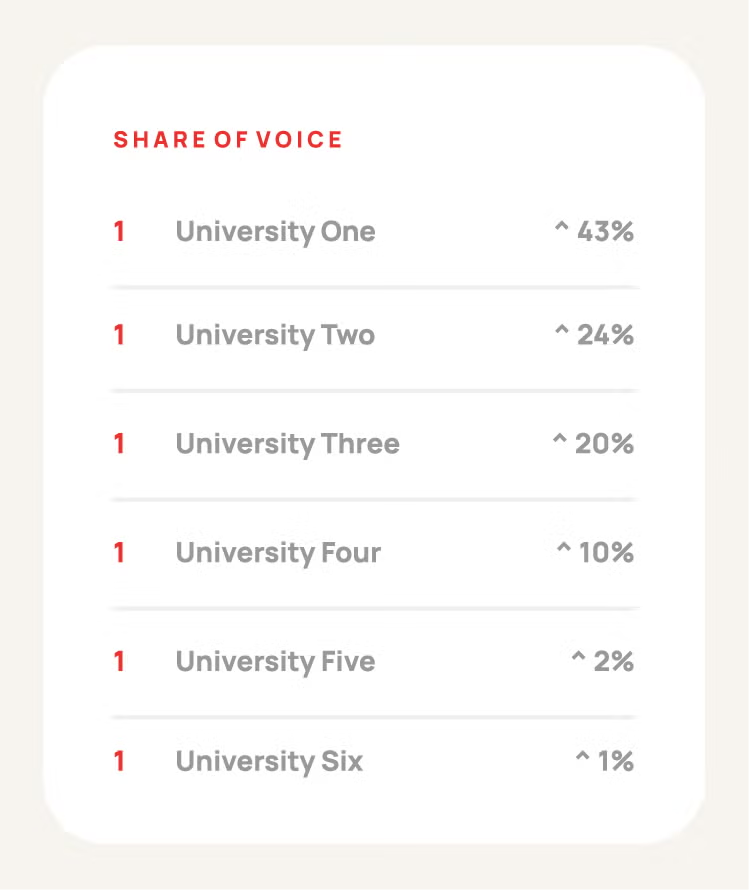

In Carnegie’s AEO Audit, we expand this approach across a much broader and more structured evaluation set. Over a 30-day period, Carnegie evaluates visibility, sentiment, and competitive positioning to show how often you appear, what AI engines are saying about your brand and programs, how you compare to peers, and where focused changes will have the greatest impact on AI search presence.

>> Learn More About Carnegie’s AEO Solution.

2. Fix the Facts on Your Highest-Impact Pages

If there’s one thing AI systems punish consistently, it’s conflicting or outdated information, and those issues most often surface on pages that drive key enrollment decisions.

Identify Your Highest-Impact Pages and Core Facts

Start by identifying ten to twenty priority pages based on enrollment volume, traffic, revenue contribution, or strategic importance. These typically include:

- High-demand program pages

- Admissions and application requirement pages

- Tuition, cost, and financial aid pages

- Visit, events, and deadline-driven pages

These pages frequently influence AI-generated answers and early student impressions, and where inaccuracies can have an impact on trust and decision-making, particularly as search continues to evolve toward more experience-driven models.

For each priority page, verify that the core facts are correct, complete, and clearly stated wherever they apply.

Program Name and Credential Type

Ensure the official program name and credential are clearly stated upon first mention. For example, fully spell out the name—Bachelor of Arts in English—in the first paragraph of the page and abbreviate to B.A. in English, Bachelor’s in English, and/or English major in future mentions.

Delivery Format

Clearly indicate whether the program or experience is offered on-campus, online, hybrid, or through multiple pathways.

Time to Completion or Timeline Expectations

Include full-time, part-time, and accelerated timelines, or key dates where applicable.

Concentrations or Specializations

List available concentrations or specializations clearly and consistently.

Tuition and Fees

Confirm how costs are expressed and whether additional fees apply.

Admissions Requirements and Deadlines

List requirements and deadlines explicitly, avoiding conditional or outdated language.

Outcomes, Licensure, and Accreditation

Document licensure alignment, accreditation status, and any verified outcomes data.

Align Facts Across Every Source

Once verified, align that information everywhere it appears, including:

- Primary program, admissions, and visit pages

- Catalog and registrar listings

- PDFs, viewbooks, and other downloadable assets

- Major program directories and rankings where edits are possible

Signal Freshness with Clear Update Dates

For content that is time-bound or interpretive—such as admissions pages, deadlines, visit information, policies, blog posts, and thought leadership—clearly signaling recency helps reduce confusion for both students and AI systems.

In those cases, a visible “last updated” date can help establish confidence that information reflects current realities.

The goal isn’t to add dates everywhere. It’s to be intentional about where freshness signals meaningfully support clarity, trust, and accuracy.

3. Restructure a Small Set of Program Pages for AI Readability

With your facts aligned, the next step is making sure your most important program pages are structured in a way that both humans and machines can easily understand.

Use a Predictable Page Structure AI Can Parse

Choose five to ten priority programs and apply a clear, predictable structure that answer engines can parse with confidence, such as:

- Program overview

- Who this program is designed for

- What students will learn

- Delivery format and scheduling

- Time to completion

- Cost and financial support options

- Admissions requirements

- Career pathways and outcomes

- Frequently asked questions

Add Information Gain to Differentiate Your Program

Rely on descriptive headings and bullet points, and avoid unnecessarily complex language. Most importantly, include at least one element of information gain: a specific detail that differentiates the program, such as outcomes data, employer partnerships, or experiential learning opportunities.

Answer Student Questions Explicitly with FAQs

And if you want to influence AI-generated answers, you need to be explicit about the questions you’re answering—FAQ sections remain one of the most effective ways to do that.

On each optimized program page, add four to six student-centered questions that directly address decision-making concerns.

Answers should be brief, factual, and supported by links to official institutional data wherever possible.

Use FAQ Schema Where Possible

If your CMS and development resources allow, mark these sections up with FAQ schema so answer engines can more reliably identify and reuse them.

If you don’t clearly answer these questions, AI will still respond, but it may not use your content to do so.

4. Build a Net-New Content Strategy for AI Visibility

Program pages matter, but institutions won’t win in AI search results by maintaining existing content alone.

Why AI Systems Prefer Explanatory Content

In practice, we’re seeing AI tools cite blog posts, explainers, and articles more often than traditional program pages, especially for the broader, earlier-stage questions students ask before they’re ready to search for a specific degree.

That means AEO success requires more than restructuring what already exists. It requires a proactive content strategy that consistently publishes new points of expertise, experience, and trust around the topics students care about.

The Types of Student Questions AI Is Answering

For many institutions, that’s not just about program marketing. It’s about painting a credible picture of student life, outcomes, belonging, and the real-world value of higher education. The kinds of pieces AI systems surface tend to answer questions like:

- What should I look for in an MBA program with an accounting concentration?

- Is community college a good first step?

- What kinds of jobs can I get in energy?

- What does it mean to be an Emerging Hispanic-Serving Institution?

In other words: content that helps students frame decisions before they compare institutions.

Start with a Small, Intent-Driven Content Pipeline

Start small. Choose five to ten priority student questions tied to your recruitment goals, informed by existing keyword research tools and site data from sources like Google Search Console.

Use those insights to build a simple content pipeline that produces a handful of focused articles:

- 3–5 new blog or explainer topics aligned to student intent

- Outlines built around direct answers + structured headings

- A short list of internal contributors or Subject Matter Experts (SMEs)

- Clear calls-to-action that connect early-funnel content to next steps

This is one of the fastest ways to expand your presence in AI-generated answers, and to build brand awareness earlier in the funnel, when students are still defining what they want.

Where We Can Help

Our AEO solution for higher ed turns insights from the audit into sustained visibility gains. Our experts deliver ongoing content development, asset optimization, visibility tracking and technical guidance to build your authority and improve performance across AI-driven search experiences.

>> Learn More About Carnegie’s AEO Solution.

5. Establish a Lightweight Governance and Maintenance Cadence

One of the biggest threats to long-term AEO success in higher education isn’t technology, it’s organizational drift.

You don’t need an enterprise-wide governance overhaul to make a difference. Start with something intentionally simple:

- A defined list of high-impact pages (programs, tuition, admissions, financial aid)

- A basic owner matrix outlining responsibility for updates

- A short monthly review checklist

- A quarterly content review cadence by college or school

Even a modest governance framework can dramatically reduce conflicting information and ensure your most important pages remain current as programs evolve.

Good enough beats perfect every time.

The Bigger Picture

AEO isn’t about chasing every AI update or trying to “game” emerging platforms. It’s about being consistently clear, accurate, and helpful in the moments when students are asking their most important questions.

If you do these five things this month, you won’t just improve your institution’s visibility in AI-driven search, you’ll build trust at the exact point where enrollment decisions are being shaped.

Ready to go deeper?

Download The Definitive Guide to AI Search for Higher Ed for practical frameworks, examples, and checklists that will help your team move from experimentation to strategy without the overwhelm.

Frequently Asked Questions About AEO in Higher Education

What is Answer Engine Optimization (AEO)?

Answer Engine Optimization (AEO) is the practice of improving how institutions appear in AI-driven search and answer environments like ChatGPT, Google AI Mode and Overviews, Gemini, and Perplexity. Instead of focusing only on rankings and clicks, AEO emphasizes clarity, accuracy, and structured content so AI systems can confidently cite and summarize your institution.

How is AEO different from traditional SEO?

SEO is designed to improve visibility in search engine results pages, while AEO focuses on how content is interpreted and reused by AI systems that generate direct answers. AEO prioritizes structured content, consistent facts, explicit question answering, and information gain over keyword density alone.

Why does AEO matter for higher education institutions?

Students increasingly ask AI platforms questions about programs, outcomes, cost, and fit before visiting institutional websites. AEO helps ensure your institution is accurately represented in those early discovery moments, when perceptions are formed and enrollment decisions begin taking shape.

What types of content help improve AEO performance?

AI systems tend to favor content that is clearly structured and informative, including program pages with consistent facts, FAQ sections, explainer articles, and blog posts that directly answer student questions. Content that demonstrates expertise, outcomes, and real-world context is more likely to be cited.

Who can we help implement AEO for higher education?

Institutions can begin improving AEO internally by auditing content, aligning program facts, and adding structured FAQs. For more advanced support, higher education–focused partners like Carnegie provide AEO audits, content optimization, technical guidance, and ongoing visibility tracking tailored to AI-driven search environments.