In Plato’s Phaedrus, King Thamus feared writing would make people forgetful and create the appearance of wisdom without true understanding. His concern was not merely about a new tool, but about a technology that would fundamentally transform how humans think, remember and communicate. Today, we face similar anxieties about generative AI. Like writing before it, generative AI is not just a tool but a transformative technology reshaping how we think, write and work.

This transformation is particularly consequential in graduate education, where students develop professional competencies while managing competing demands, research deadlines, teaching responsibilities, caregiving obligations and often financial pressures. Generative AI’s appeal is clear; it promises to accelerate tasks that compete for limited time and cognitive resources. Graduate students report using ChatGPT and similar tools for professional development tasks, such as drafting cover letters, preparing for interviews and exploring career options, often without institutional guidance on effective and ethical use.

Most AI policies focus on coursework and academic integrity; professional development contexts remain largely unaddressed. Faculty and career advisers need practical strategies for guiding students to use generative AI critically and effectively. This article proposes a four-stage framework—explore, build, connect, refine—for guiding students’ generative AI use in professional development.

Professional Development in the AI Era

Over the past decade, graduate education has invested significantly in career readiness through dedicated offices, individual development plans and co-curricular programming—for example, the Council of Graduate Schools’ PhD Career Pathways initiative involved 75 U.S. doctoral institutions building data-informed professional development, and the Graduate Career Consortium, representing graduate-focused career staff, grew from roughly 220 members in 2014 to 500-plus members across about 220 institutions by 2022.

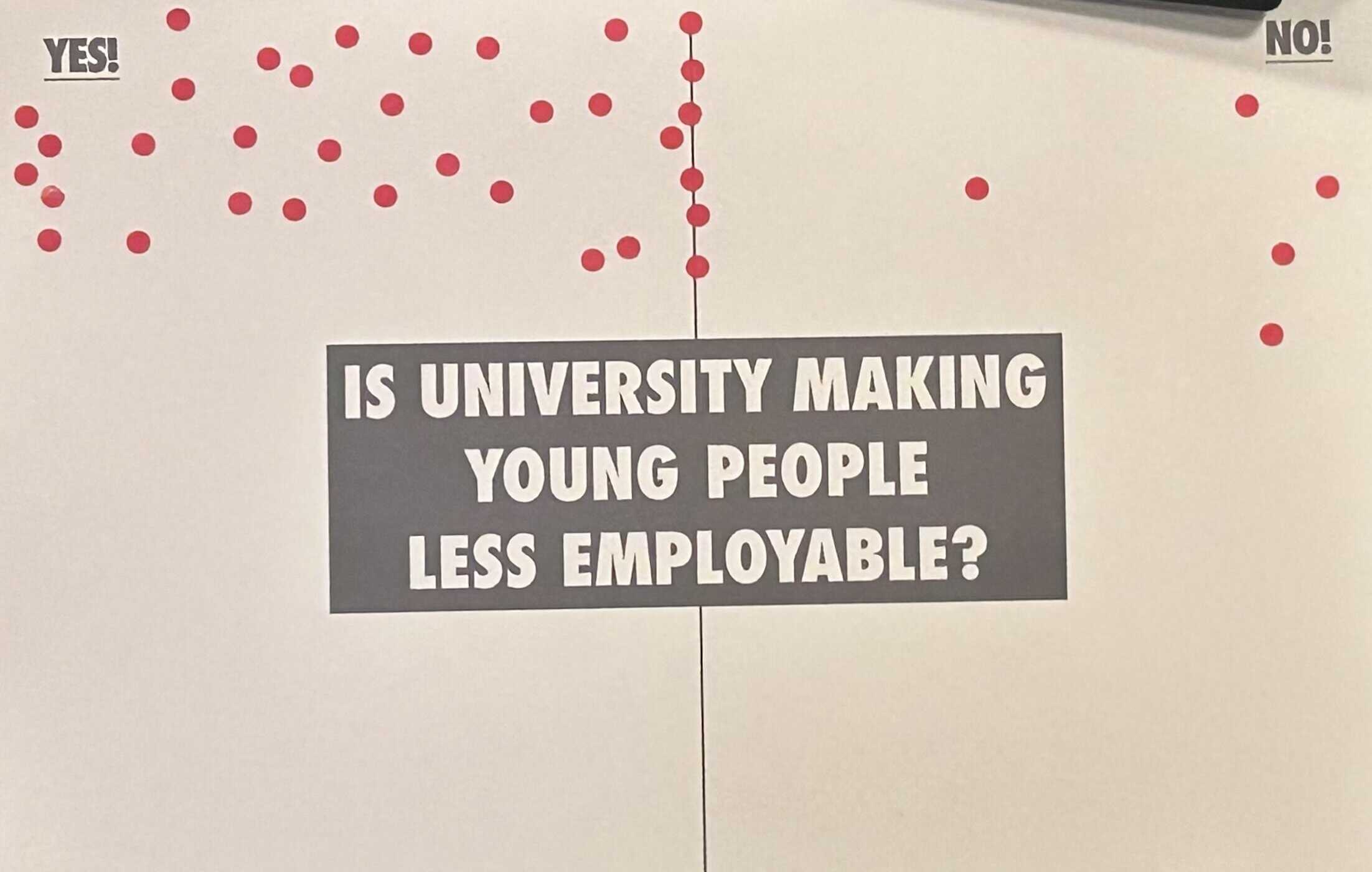

These investments reflect recognition that Ph.D. and master’s students pursue diverse career paths, with fewer than half of STEM Ph.D.s entering tenure-track positions immediately after graduation; the figure for humanities and social sciences also remains below 50 percent over all.

We now face a different challenge: integrating a technology that touches every part of the knowledge economy. Generative AI adoption among graduate students has been swift and largely unsupervised: At Ohio State University, 48 percent of graduate students reported using ChatGPT in spring 2024. At the University of Maryland, 77 percent of students report using generative AI, and 35 percent use it routinely for academic work, with graduate students more likely than undergraduates to be routine users; among routine student users, 38 percent said they did so without instructor guidance.

Some subskills, like mechanical formatting, will matter less in this landscape; higher-order capacities—framing problems, tailoring messages to audiences, exercising ethical discernment—will matter more. For example, in a 2025 National Association of Colleges and Employers survey, employers rank communication and critical thinking among the most important competencies for new hires, and in a 2024 LinkedIn report, communication was the most in-demand skill.

Without structured guidance, students face conflicting messages: Some faculty ban AI use entirely, while others assume so-called digital natives will figure it out independently. This leaves students navigating an ethical and practical minefield with high stakes for their careers. A framework offers consistency and clear principles across advising contexts.

We propose a four-stage framework that mirrors how professionals actually learn: explore, build, connect, refine. This approach adapts design thinking principles, the iterative cycle of prototyping and testing, to AI-augmented professional development. Students rapidly generate options with AI support, test them in low-stakes environments and refine based on feedback. While we use writing and communication examples throughout for clarity, this framework applies broadly to professional development.

Explore: Map Possibilities and Surface Gaps

Exploring begins by mapping career paths, fellowship opportunities and professional norms, then identifying gaps in skills or expectations. A graduate student can ask a generative AI chatbot to infer competencies from their lab work or course projects, then compare those skills to current job postings in their target sector to identify skills they need to develop. They can generate a matrix of fellowship opportunities in their field, including eligibility requirements, deadlines and required materials, and then validate every detail on official websites. They can ask AI to describe communication norms in target sectors, comparing the tone and structure of academic versus industry cover letters—not to memorize a script, but to understand audience expectations they will need to meet.

Students should not, however, rely on AI-generated job descriptions or program requirements without verification, as the technology may conflate roles, misrepresent qualifications or cite outdated information and sources.

Build: Learn Through Iterative Practice

Building turns insight into artifacts and habits. With generative AI as a sounding board, students can experiment with different résumé architectures for the same goal, testing chronological versus skills-based formats or tailoring a CV for academic versus industry positions. They can generate detailed outlines for an individual development plan, breaking down abstract goals into concrete, time-bound actions. They can devise practice tasks that address specific growth areas, such as mock interview questions for teaching-intensive positions or practice pitches tailored to different funding audiences. The point is not to paste in AI text; it is to lower the barriers of uncertainty and blank-page intimidation, making it easier to start building while keeping authorship and evidence squarely in the student’s hands.

Connect: Communicate and Network With Purpose

Connecting focuses on communicating with real people. Here, generative AI can lower the stakes for high-pressure interactions. By asking a chatbot to act the part of various audience members, students can rehearse multiple versions of a tailored 60-second elevator pitch, such as for a recruiter at a career fair, a cross-disciplinary faculty member at a poster session or a community partner exploring collaboration. Generative AI can also simulate informational interviews if students prompt the system to ask follow-up questions or even refine user inputs.

In addition, students can leverage generative AI to draft initial outreach notes to potential mentors that the students then personalize and fact-check. They can explore networking strategies for conferences or professional association events, identifying whom to approach and what questions to ask based on publicly available information about attendees’ work.

Even just five years ago, completing this nonexhaustive list of networking tasks might have seemed an impossibility for graduate students with already crammed agendas. Generative AI, however, affords graduate students the opportunity to become adept networkers without sacrificing much time from research and scholarship. Crucially, generative AI creates a low-risk space to practice, while it is the student who ultimately supplies credibility and authentic voice. Generative AI cannot build genuine relationships, but it can help students prepare for the human interactions where relationships form.

Refine: Test, Adapt and Verify

Refining is where judgment becomes visible. Before submitting a fellowship essay, for example, a student can ask the generative AI chatbot to simulate likely reviewer critiques based on published evaluation criteria, then use that feedback to align revisions to scoring rubrics. They can A/B test two AI-generated narrative approaches from the build stage with trusted readers, advisers or peers to determine which is more compelling. Before a campus talk, they can ask the chatbot to identify jargon, unclear transitions or slides with excessive text, then revise for audience accessibility.

In each case, verification and ownership are nonnegotiable: Students must check references, deadlines and factual claims against primary sources and ensure the final product reflects their authentic voice rather than generic AI prose. A student who submits an AI-refined essay without verification may cite outdated program requirements, misrepresent their own experience or include plausible-sounding but fabricated details, undermining credibility with reviewers and jeopardizing their application.

Cultivate Expert Caution, Not Technical Proficiency

The goal is not to train students as prompt engineers but to help them exercise expert caution. This means teaching students to ask: Does this AI-generated text reflect my actual experience? Can I defend every claim in an interview? Does this output sound like me, or like generic professional-speak? Does this align with my values and the impression I want to create? If someone asked, “Tell me more about that,” could I elaborate with specific details?

Students should view AI as a thought partner for the early stages of professional development work: the brainstorming, the first-draft scaffolding, the low-stakes rehearsal. It cannot replace human judgment, authentic relationships or deep expertise. A generative AI tool can help a student draft three versions of an elevator pitch, but only a trusted adviser can tell them which version sounds most genuine. It can list networking strategies, but only actual humans can become meaningful professional connections.

Conclusion

Each graduate student brings unique aptitudes, challenges and starting points. First-generation students navigating unfamiliar professional cultures may use generative AI to explore networking norms and decode unstated expectations. International students can practice U.S. interview conventions and professional correspondence styles. Part-time students with limited campus access can get preliminary feedback before precious advising appointments. Students managing disabilities or mental health challenges can use generative AI to reduce the cognitive load of initial drafting, preserving energy for higher-order revision and relationship-building.

Used critically and transparently, generative AI can help students at all starting points explore, build, connect and refine their professional paths, alongside faculty advisers and career development professionals—never replacing them, but providing just-in-time feedback and broader access to coaching-style support.

The question is no longer whether generative AI belongs in professional development. The real question is whether we will guide students to use it thoughtfully or leave them to navigate it alone. The explore-build-connect-refine framework offers one path forward: a structured approach that develops both professional competency and critical judgment. We choose guidance.