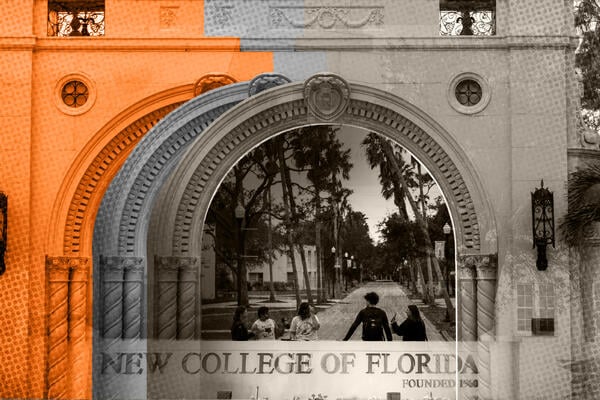

More than two years into a conservative takeover of New College of Florida, spending has soared and rankings have plummeted, raising questions about the efficacy of the overhaul.

While state officials, including Republican governor Ron DeSantis, have celebrated the death of what they have described as “woke indoctrination” at the small liberal arts college, student outcomes are trending downward across the board: Both graduation and retention rates have fallen since the takeover in 2023.

Those metrics are down even as New College spends more than 10 times per student what the other 11 members of the State University System spend, on average. While one estimate last year put the annual cost per student at about $10,000 per member institution, New College is an outlier, with a head count under 900 and a $118.5 million budget, which adds up to roughly $134,000 per student.

Now critics are raising new questions about NCF’s reputation, its worth and its future prospects as a public liberal arts college.

A Spending Spree

To support the overhaul, the state has largely issued a blank check for New College, with little pushback from officials.

While some—like Florida Board of Governors member Eric Silagy—have questioned the spending and the state’s return on investment, money keeps flowing. Some critics say that’s because the college is essentially a personal project of the governor.

“With DeSantis, I think his motivation for the takeover was that he was running for president and he needed some educational showcase. And he picked us because we were an easy target,” one New College of Florida faculty member said, speaking on the condition of anonymity.

But now, two-plus years and one failed presidential run later, money continues to flow to the college to help establish new athletics programs and recruit larger classes each year. Part of the push behind such recruiting efforts, the faculty member said, is because of retention issues.

“It’s kind of like a Ponzi scheme: Students keep leaving, so they have to recruit bigger and bigger cohorts of students, and then they say, ‘Biggest class ever’ because they have to backfill all the students who have left,” they said.

Nathan Allen, a New College alum who served as vice president of strategy at NCF for almost a year and a half after the takeover but has since stepped down, echoed that sentiment, arguing that administrators are spending heavily with little return on investment and have failed to stabilize the institution. He also said they’ve lost favor with lawmakers, who have expressed skepticism in conversations—even though New College is led by former Speaker of the Florida House Richard Corcoran, a Republican.

“I think that the Senate and the House are increasingly sensitive to the costs and the outcomes,” Allen said. “Academically, Richard’s running a Motel 6 on a Ritz-Carlton budget, and it makes no sense.”

While New College’s critics have plenty to say, supporters are harder to find.

Inside Higher Ed contacted three NCF trustees (one of whom is also a faculty member), New College’s communications office, two members of the Florida Board of Governors (including Silagy) and the governor’s press team for this article. None responded to requests for comment.

A Rankings Spiral

Since the takeover, NCF has dropped nearly 60 spots among national liberal arts colleges in the U.S. News & World Report Best Colleges rankings, from 76th in 2022 to 135th this year.

Though critics have long argued that such rankings are flawed and various institutions have stopped providing data to U.S. News, the state of Florida has embraced the measurement. Officials, including DeSantis, regularly tout Florida’s decade-long streak as the top state for higher education, and some public universities have built rankings into their strategic plans. But as most other universities in the state are climbing in the rankings, New College is sliding, a fact unmentioned at a Monday press conference featuring DeSantis and multiple campus leaders.

Corcoran, the former Republican lawmaker hired as president shortly after the takeover, did not directly address the rankings slide when he spoke at the briefing at the University of Florida. But in his short remarks, Corcoran quibbled over ranking metrics.

“The criteria is not fair,” he said.

Specifically, he took aim at peer assessment, which makes up 20 percent of the rankings criteria. Corcoran argued that Florida’s institutions, broadly, suffer from a negative reputation among their peers, whose leaders take issue with the conservative agenda DeSantis has imposed on colleges and universities.

“This guy has changed the ideology of higher education to say, ‘We’re teaching how to think, not what to think,’ and we’re being peer reviewed by people who think that’s absolutely horrendous,” Corcoran said.

An Uncertain Future

As New College’s cost to the state continues to rise and rankings and student outcomes decline, some faculty members and alumni have expressed worry about what the future holds. While some believe DeSantis is happy to keep pumping money into New College, the governor is term limited.

“It’s important to keep in mind that New College is not a House or Senate project; it’s not a GOP project. It’s a Ron DeSantis project. Richard Corcoran has a constituency of one, and that’s Ron,” Allen said.

Critics also argue that changes driven by the college’s administration and the State University System—such as reinstating grades instead of relying on the narrative evaluations NCF has historically used and limiting course offerings, among other initiatives—are stripping away what makes New College special. They argue that as it loses traditions, it’s also losing differentiation.

Rodrigo Diaz, a 1991 New College graduate, said that the Sarasota campus had long attracted quirky students who felt stifled by more rigid academic environments. Now the administration and state are imposing “uniformity,” he said, which he argued will be “the death of New College.”

And some critics worry that death is exactly what lies ahead for NCF. The anonymous faculty member said they feel “an impending sense of doom” at New College and fear that it could close within the next two years. Allen said he has heard a similar timeline from lawmakers.

Even Corcoran referenced possible closure at a recent Board of Governors meeting.

In his remarks, the president emphasized that a liberal arts college should “produce something different.” And “if it doesn’t produce something different, then we should be closed down. But if we are closed down, I say this very respectfully, Chair—then this Board of Governors should be shut down, too,” Corcoran said, noting that many of its members have liberal arts degrees.

To Allen, that remark was an unforced error that revealed private conversations about closure are likely happening behind closed doors.

“I think Richard made the mistake of not realizing those conversations haven’t been public. He made them public, but the Board of Governors is very clearly talking to him about that,” he said.

But Allen has floated an alternative to closure: privatization.

Founded in 1960, New College was private until it was absorbed by the state in 1975. Allen envisions “the same deal in reverse” in a process that would be driven by the State Legislature.

“I think that the option set here is not whether it goes private or stays public, I think it’s whether it goes private or closes,” Allen said. “And I think that that is increasingly an open conversation.”

(Though NCF did not respond to media inquiries, Corcoran has voiced opposition to such a plan.)

Allen has largely pushed his plan privately, meeting with lawmakers, faculty, alumni and others. Reactions are mixed, but the idea seems to be a growing topic of conversation on campus. The anonymous faculty member said they are increasingly warming to the idea as the only viable solution, given that they believe the other option is closure within the next one to three years.

“I’m totally convinced this is the path forward, if there is a path forward at all,” they said.

Diaz said the idea is also gaining momentum in conversations with fellow alumni. He called himself “skeptical but respectful” of the privatization plan and said he has “a lot of doubt and questions.” But Diaz said that he and other alumni should follow the lead of faculty members.

“Now, if the faculty were to jump on board with the privatization plan, then I think that people like myself—alumni like myself, who are concerned for the future of the college—should support the faculty,” Diaz said. “But the contrary is also true. If the faculty sent up a signal that ‘We don’t like this, we have doubts about this,’ then, in good conscience, I don’t think I could back the plan.”