How do we teach effectively—and humanly—in this age of AI?

New advances in artificial intelligence break news at such a rapid pace that many of us have difficulties keeping up. Dinuka Gunaratne gave a detailed summary of many different AI tools in his “Carpe Careers” article published in July; yet more tools will likely appear in the next months and years in an exponential explosion. How do we, as educators (new and established Ph.D.s) design curriculum and classes with these new AI tools being released every few weeks? How do we design effective assignments that teach critical analysis and logical thought while knowing that our students, too, have access to these tools?

Many existing AI tools can be used to assist with course design. However, I will provide some insight on methods of pedagogy that emphasize personalized learning regardless of what new technology becomes available.

Some questions educators are now thinking about include:

- How do I design an assignment so the student cannot just prompt an AI tool to complete it?

- How do I design the course so that the student can choose whether or not to use AI tools—and how do I assess these two groups of students?

Below, I outline some wise teaching practices with an eye toward helping students develop core skills including critical thinking, problem-solving, teamwork, creativity and—the most essential skill of all—curiosity.

Making the Most Out of Class Time

An effective course utilizes a combination of teaching strategies. I outline three here.

- Make sure that your class is generative so that when you give an assignment, it reaches as far back as day one. A generative learning model is one in which each week is built upon the previous one, and in which a student is assessed on the knowledge they have cumulatively accrued.

- Hold interactive in-person activities in each class, building upon the previous assignments and content.

- Flip the classroom so that class time is used for discussion and not a monologue presentation from you. If you can assign videos or reading assignments for students to view or read prior to class, then you can use class time to discuss the content or reinforce the learning with group activities.

Here is an example of combining these tools in the buildup to a presentation from one of my classes.

- Week 1: Each student writes and brings a one-page summary of their research so that peers can provide feedback. I provide feedback training in class before the peer readings take place.

- Week 2: Using the peer feedback of the summary, each student creates one slide summarizing their research for a three-minute thesis (3MT) and brings the slide to class to receive peer feedback.

- Week 3: Students practice presentation skills through an activity called “slide karaoke,” in which a student has one minute to present a simple slide they have never seen before. They are then given feedback by peers and the instructor on general presentation skills. I provide peer feedback training before the presentations.

- Week 4: Students implement the general feedback from slide karaoke and give practice 3MT presentations to receive specific peer and mentor feedback on the content. These mentors are usually students from the year before who revisit the class.

- Week 5: Students give the final 3MT in front of judges and peers for evaluation.

- Week 6: Students write a summary of what was learned from the entire generative experience.

This sequence of assignments is personalized so that the final report can only be about the student’s individual experience. While students might want to use AI tools to edit or organize their ideas, ChatGPT or other AI tools cannot possibly know what happened in the classroom—only the student can write about it.

For larger classes in which a presentation from each student may not be possible, here is another example.

- Week 1: A video or reading assigned to students to view/read before class discusses the basics of DNA and inheritance. An in-class assignment involves a group discussion on Mendelian inheritance problem sets.

- Week 2: Before class, students read an article on how DNA is packaged; the in-class discussion focuses on the molecules involved in chromatin structure.

- The next classes all have either prereads or videos, which students discuss in class, and the content builds up to a more complex genetic mechanism, such as elucidating the gene for a disease. The final report could be “summarize how one could find a gene responsible for a certain disease using the discussion points we had in class.” In this scenario as well, the student is taking the personalized class experience and incorporating the ideas into the final report, something that cannot be wholly outsourced to any AI tool.

If you decide to embrace AI tools in the classroom, you can still teach critical thinking and creativity by asking the students to use AI to write a report on a topic discussed in class—and then in part two of the assignment, ask them to assess the AI-generated report, cite the proper references and correct any mistakes, content or grammar-wise.

I sometimes show an example of this in class to demonstrate to students that AI makes mistakes, rather than giving it as an assignment. But it is something you might want to try making an optional method for an assignment. Students can declare whether they used AI or not on their submission. As an instructor, you will need to design two rubrics for these different groups. Group one will have a rubric based on content, grammar, references, logical thought and organization, and clarity. Group two (those who use AI) will have a rubric consisting of the same components in addition to an evaluation of how well the student found the AI mistakes.

Applying for Teaching Positions

If you are applying for a teaching position, you should address AI in your teaching dossier and how you may or may not incorporate it—but at the very least, discuss its effects on higher education. Many articles and books on this topic exist, including Teaching with AI: A Practical Guide to a New Era of Human Learning, by José Antonio Bowen and C. Edward Watson (Johns Hopkins Press, 2024); Robot-Proof: Higher Education in the Age of Artificial Intelligence, by Joseph E. Aoun (MIT Press, 2017); and Generative AI in Higher Education, by Cecilia Ka Yuk Chan and Tom Colloton (Routledge, 2024).

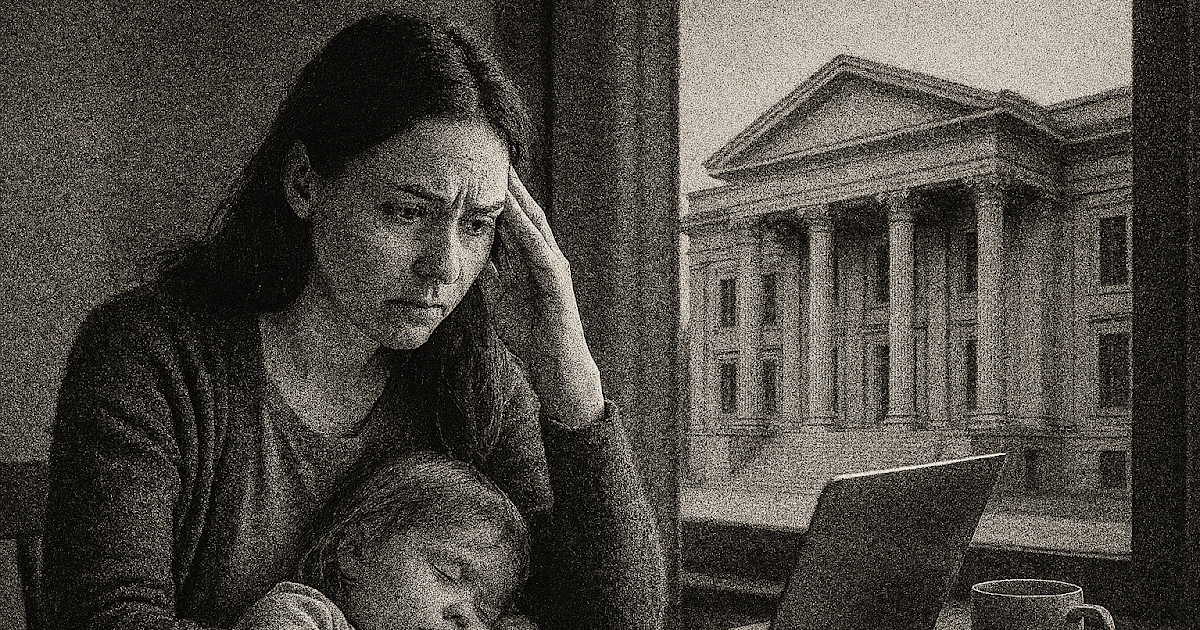

Yet even as we consider how to integrate AI in our teaching, we must not forget the human experience at work in all that we do. We can emphasize things like 1) encouraging students to meet with us in person or even for a walk as opposed to a virtual meeting and 2) assessing what emotions students bring to the meeting or class and how that may affect the dynamics. We as educators should harness the human side of teaching, including the classroom experience and the in-class group work, so that the “final” assessments build directly out of these personalized learnings.

For those venturing into a career that involves teaching or mentoring, develop teaching strategies and tools that center the human experience and include them in your teaching dossier. Your application will shine.