September 8, 2025, by Dr. Chet Haskell: It is well known that many small American private non-profit academic institutions face serious financial pressures. Typically defined as having 3000 or fewer students, more than 170 of these have been forced to close in the past two decades. Numerous others have entered into various mergers or acquisitions, often with well-documented negative impacts on students, faculty, staff, alumni and local communities. Of the more than 1100 such institutions, at least 900 continue to be a risk.

The basic problems responsible for this trend are also well-known. Most institutions lack significant endowments and are thus almost totally dependent on tuition and fee revenues from enrolled students. Only 60 such small institutions have per student endowments in excess of $200,000. The remainder have far less.

The only additional potential source of revenue – gifts and donations –is generally neither large nor consistent enough to offset enrollment-related declines. While the occasional donation or bequest in the millions of dollars garners attention, most institutions raise much smaller amounts regularly.

Enrollment declines are the existential threat to many of these smaller colleges and universities. These declines are also well-documented. There simply will be fewer high school graduates in the US in the coming decade or more. This reality creates a highly competitive environment, especially in regions with many of these institutions.

Demographic worries are augmented by broad concerns about the cost of higher education and the imputed return on such an investment by students and families. Governmental policies such as limitations on international students or restrictions on immigration further add to the problem. Also, these institutions not only compete with each other for students, but they also compete with colleges and universities of the public sector and a growing number of for-profit entities.

Most of these 900 or so institutions have high quality programs, often described under the term “liberal arts”. Many are differentiated by a specialization or an emphasis. However, at their core they are very similar. The basic concept of a personal scale four-year undergraduate educational experience provided in a residential campus setting has a long history and is highly valued by many students and faculty alike. These institutions have lengthy, strong histories, loyal alumni and important roles in their local communities.

The fact is that it is difficult to differentiate among many of these institutions. Not only their scale or their general model of personalized undergraduate education are similar, but many of their basic messages sound the same. A review of the websites of these schools results in striking consistencies of stated “unique” missions, programs, facilities, faculty and even marketing materials.

Their approaches to financial challenges are also similar. There is considerable competition on price. Most of these institutions discount their formal tuition rates by 50% or more. Initiatives to grow enrollments support an industry of educational consultants whose recommended initiatives are themselves similar and, even if successful, are quickly copied, thus reducing advantages.

Some have tried to compete by raising money for new, attractive facilities through dipping into limited endowments, borrowing or securing external major gifts. These shiny new buildings – athletic facilities, science centers, student centers – are assumed to provide an edge in student recruitment. In some cases, this works. However, in many others the new facilities do not come with long term maintenance and eventually add to increased on-going institutional expense. The end result is often another demonstration of similarity.

Some institutions have tried to branch out into selected graduate programs, perhaps based on a strong group of undergraduate faculty. Success is often limited for multiple reasons. Graduate students in commonly introduced professional fields such as business or nursing do not naturally align with an undergraduate in-person academic calendar. Older students, especially those in careers, are reluctant to come to a campus for class twice a week. Even if there is sufficient interest in such a program, it is difficult to increase in scale because of the limits of distance and geography. And most of these institutions lack significant expertise and technology do conduct effective on-line operations.

Their institutional similarities extend to their governance. Typically, there is a Board of Trustees, all of whom are volunteers, often with heavy alumni representation. These boards generally lack expertise or perspective on the challenges of higher education and thus are dependent on the appointed executive leadership. They often take a short-term perspective and lack strategic foresight that may be most valuable in times of uncertainty and external changes.

Even when trustees have financial experience from other fields, their common approach to small institutions is to bemoan any lack of enrollments. Most do not make significant personal financial contributions, particularly if they think the institution is struggling to survive. The assumed budget goal is basically a balanced budget and when one does not control revenues, one focuses on the more controllable expense side, trying to balance budgets solely on cuts. Board members serve because they want to support the institution, but many are risk adverse. For example, a fear of being associated with an institution that might generate possible legal liability for the board member means a first concern usually involves whether there is sufficient insurance.

While every institution is indeed different in its own way, they also are very similar. What explains this?

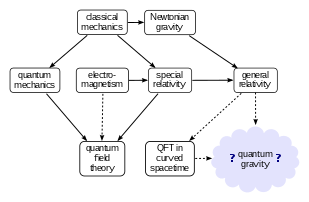

One possible way of explanation is provided by the organizational theorists Walter Powell and Paul DiMaggio who in 1983 (updated in 1991) published a seminal piece on what they called ”institutional isomorphism and collective rationality.” [1]They argued that ”institutions in the same field become more homogenous over time without become more efficient or more successful” and identified three basic reasons for such a tendency.

Coercive isomorphism – similarities imposed externally on the institutions. In higher education, good examples would be Federal government policies around student financial aid or the requirements of both regional and specialized accreditors. Every institution operates within a web of regulation and financial incentives that impose requirements on all and work to limit innovation.

Mimetic processes – similarities that arise because of standard responses to uncertainty. Prime examples in higher education are the increasingly common responses to the quest for enrollment growth. As noted, numerous consultants purport to improve enrollments, but the gains typically are limited, as other institutions mimic the same approach. In another example, recent surveys show that almost all institutions expect to be users of artificial intelligence models to promote marketing in the service of admissions, as if this is a “magic wand”. If one institution makes strides in this area, others will follow. The result will be more similarity, not less. It is a bit like the Ukrainian-Russian war, where Ukraine originally had clear advantages using drone technology until that technology was matched by the Russians, leading to a form of stalemate. As DiMaggio and Powell note, ”organizations tend to model themselves after similar organizations in their field that they perceive as more legitimate or successful.”[2]

Normative pressures – similarities that arise from common “professional” expectations. The authors identify two important aspects of professionalization: the common basis of higher education credentials and the legitimation produced by these credentials and “the growth and elaboration of professional networks.” Examples include common faculty and senior administrator qualification requirements. Another would be so-called “best practices” in support areas like student affairs. “Such mechanisms create a pool of almost interchangeable individuals who occupy similar positions.”[3] Recently, Hollis Robbins pointed out the commonalities in paths to academic leadership positions, likening these to the Soviet nomenklatura process through which a leader progresses in one’s career.[4] Evidence of this is obvious through a cursory review of the qualifications and desired qualities posted in searches for college and university presidents or other senior administrators. Most searches end up looking for and hiring individuals with very similar qualifications and experience.

The implications of such pressures and processes are several. With common values and similar personnel, “best practices” do not lead to essential changes. Innovation is quickly copied. Indeed, it becomes increasing difficult to differentiate an institution from competitors. Common regulatory structures, declining student pools, increased competition and a lack of resources for investment all combine to enhance similarity over difference. In some sense, it is almost a form of commodification where price does in fact matter, but the “product” basically the same, especially in the minds of the larger population of potential students and families.

What is to be done?

Leadership Must Confront Their Institution’s Reality

Confronting reality has many aspects, but the leaders of every institution must be clear-eyed and unsentimental about where it stands and where it is headed. This is an essential role for boards and executive leadership.

First and foremost, the mission of the institution must be understood in realistic and practical ways. What is the institution’s purpose and what is required to fulfill that purpose? Institutional mission is central as it should drive an appreciation for the current situation of the institution, provide clarity regarding longer term goals and bringing into focus the necessary means to move forward.

With clarity of mission must come a full understanding the of institution’s financial situation, its opportunities and the longer term needs required to achieve mission goals. Building multi-year mission-oriented budgets based on surpluses (positive margins) is key. Sometimes restructuring and cuts are necessary and thus leadership must make sure all faculty and staff have a clear understanding of reality and the strategy for addressing it.

A clear understanding by all of the marginal results (positive and negative) of major components is also critical. Some elements or units return significant positive margins. Others less so. And some return negative margins, often year after year. Yet, some of these less financially productive elements may be essential to mission and must be balanced or subsidized by other elements. At the end of the day, it is the margin of the entire institution that matters. And, as the saying goes, “no margin, no mission.” However, the opposite is also true. Institutions that are unclear about their mission will be challenged to attract and motivate students, faculty, staff or major donations.

Every institution must worry about enrollments as the largest source of revenue. Declining enrollments force expense restraints. Every institution must also be concerned about growing enrollments as a key prerequisite of financial stability. Institutions operating on thin or negative margins cannot hope to achieve their mission goals without some form of growth, including having the resources to invest in growth. Without some forms of growth, an institution will either be at risk or will have to make sometimes radical changes in order to continue to pursue mission goals. The only real alternative is to amend the mission and the definition of its success.

The other important point is that all institutions are subject to unexpected external pressures that they cannot control. Examples would be 9/11, the 2008-09 Great Recession, the COVID pandemic or the advent new government policies, such as those confronting all institutions today. Coping with such events requires having some financial resiliency, strong leadership and creativity.

Yet, the combination of external pressures and the realities of small-scale institutions operating on thin margins in the face of extensive competition may mean that even the best managed and led organizations will confront existential risk.

For many institutions, merging or partnering with another institution may be the only realistic path. While there often is reluctance to cede independence to another institution, mergers are hardly new, as consolidation in US higher education is hardly a new phenomenon. There are several hundred examples of mergers, many going back a century or more. Washington and Jefferson College in Pennsylvania in 1865 is the result of such an arrangement, as is Case Western Reserve University in Ohio a century later. In addition to these mergers, hundreds of other institutions have simply closed, including at least 170 in the past twenty years.

Additionally, may institutions may be placed to take advantage of consortium relationships with other institutions. Again, there are numerous examples of institutions seeking to improve their situations through this form of collaboration. Participating institutions collaborate on such things as sharing costs or providing a wider range of student options, while remaining independent. However, this model, while valuable in many ways, rarely provides major financial advantages except at the margins. And successful consortia require a certain degree of independent sustainability for each member.

Still others may be able find opportunity in growth through symbiosis. The recent Coalition for the Common Good begun by Antioch and Otterbein universities is an example. Other variants are possible. However, again such middle ground models also assume a basic stability of the members. As stated by Coalition president, John Comerford, “we are looking for a sweet spot of resources. This is not a way to save a school on death’s door. It’s also probably not useful to a school with billions in their endowment. Institutions in the big middle ground both need to look at new business models and likely have some flexibility to invest in them.” This type of model will not work in many cases.

The point is that many of these small college will continue to be at risk as long as they are tuition dependent within a shrinking pool of potential students and insufficient external support. Fewer and fewer small institutions will be able to survive independently simply because of the financial challenges inherent in their small-scale model.

Small undergraduate institutions represent the highest ideals of higher education. They are a key source for graduate students and future professors. They are central to their communities. Their strengthening and preservation as a class is an essential element of the American higher education ecosystem with its wide range of institutional models and opportunities. But this does not mean all can survive.

The leaders of every institution need to have a clear and practical plan for the maintenance of their independence, while also being open to careful consideration of alternatives, exploring potential alternatives well before they face a crisis.

Notes:

- DiMaggio, Paul and Powell, Walter, The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields in DiMaggio and Powell, The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis, University of Chicago Press, 1991. (pp.63-82)

- Ibid. p. 70

- Ibid. p. 71

- Hollis Robbins, The Higher Ed Nomenklatura? Inside Higher Education, May 12, 2025

The next essay in this series will examine in some detail the steps in a process that begins with acknowledging the possible need for a partner and hopefully results in an agreement that is implemented.

Dr. Chet Haskell is Senior Consultant and Higher Education Strategist at Edu Alliance Group. He brings over four decades of leadership and consulting experience in higher education, with a career spanning the U.S., Europe, Latin America, and Asia. He has held senior roles, including President of the Monterey Institute of International Studies and Cogswell Polytechnical College, Dean and de facto Provost at Simmons College, and 13 years of leadership positions at Harvard University and five years in senior administrative roles at the University of Southern California.

As Provost and Chief Academic Officer of Antioch University, he helped lead the creation of the Coalition for the Common Good, a groundbreaking alliance with Otterbein University. Internationally, Dr. Haskell has advised universities in Mexico, Spain, Holland, and Brazil and served as a consultant to the Council for Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA), the Western Association of Schools and Colleges (WASC) and the Council on International Quality Group.

A respected accreditation expert, he has served as a WSCUC peer reviewer and as an international advisor to ANECA (Spain) and ACAP (Madrid). He is a frequent speaker at global conferences and meetings.