In the public imagination, universities are bastions of knowledge, debate, and progress. Yet beneath the veneer of research and scholarship lies a more troubling reality: many American institutions of higher education are deeply enmeshed in structures of global power, empire, and inequality. From elite research universities to sprawling public institutions, higher education in the United States not only reflects the hierarchies of the world it inhabits but actively reproduces them.

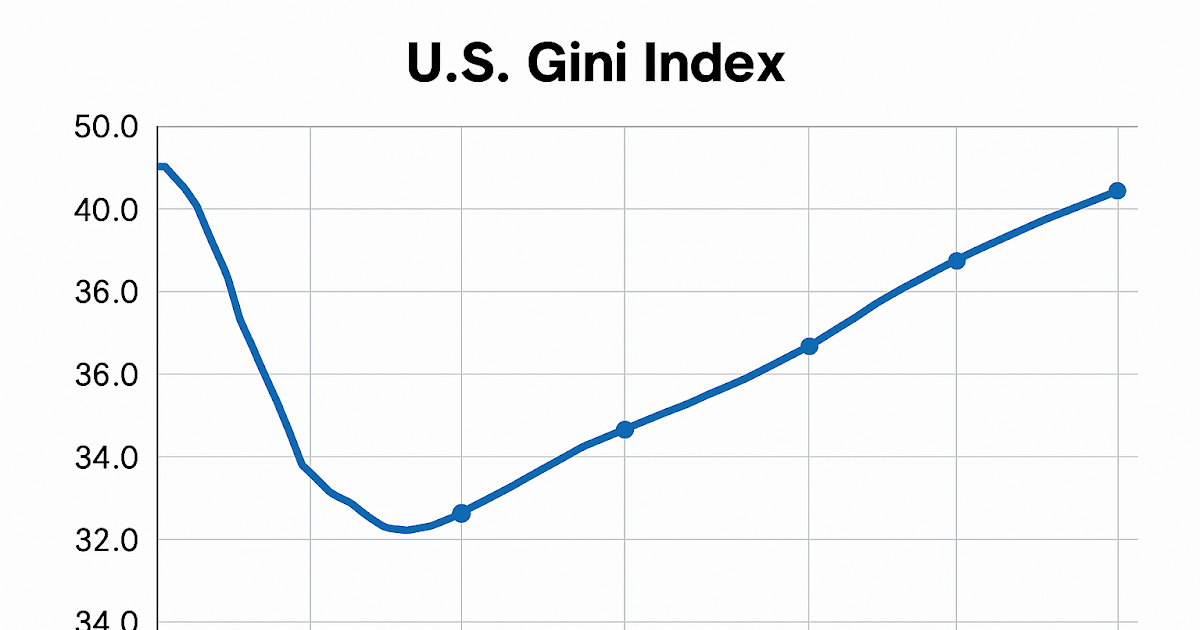

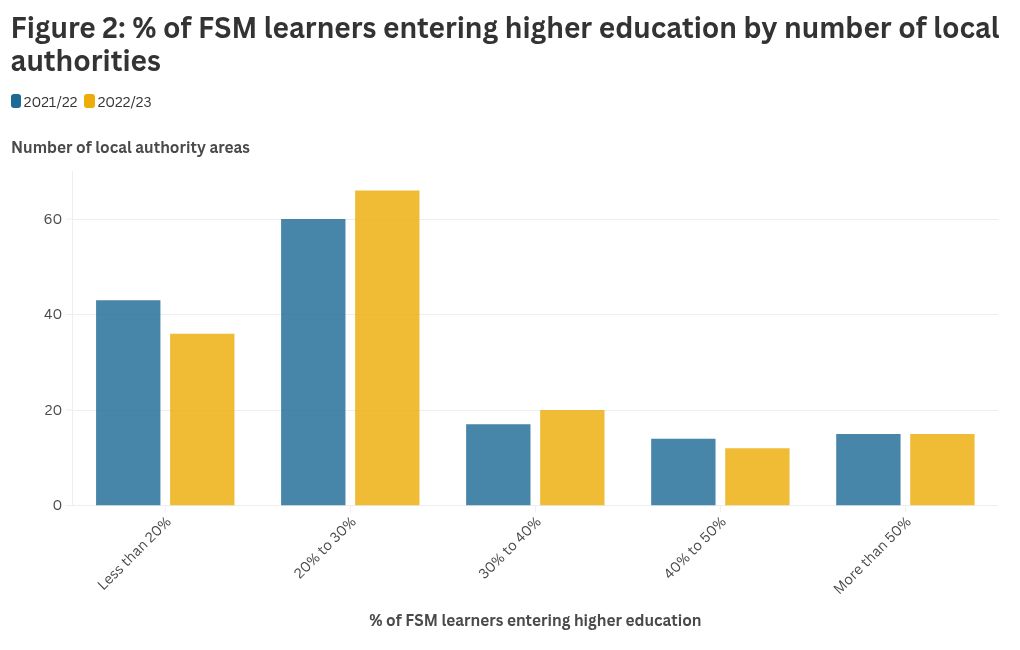

The complicity of universities is neither incidental nor simply a matter of individual choices by administrators. As scholars have noted, the mechanisms of institutional power are deeply structural. Economic and geopolitical pressures shape research priorities, hiring practices, and funding relationships. Academic capitalism, which treats universities as competitive, profit-driven enterprises, has become the norm rather than the exception (Slaughter & Rhoades, 2022). Faculty labor is increasingly precarious, tenure-track opportunities are scarce, and institutional priorities are subordinated to external market logics. The consequences are profound: the promise of knowledge as a public good is eroded, and access is increasingly limited to those already advantaged by class, race, or geography.

U.S. universities’ entanglement with empire is global in scope. Historical patterns of colonialism persist in the form of research agendas, partnerships, and international collaborations that favor dominant powers. The post-apartheid South African university system, for example, demonstrates how neoliberal pressures reshape higher education into corporatized, commodified institutions, constraining equity and social justice efforts (Jansen, 2024). Similarly, elite U.S. institutions reproduce intersectional inequalities, privileging white male scholars while marginalizing women and scholars from the Global South, consolidating a global hierarchy of knowledge production (Smith & Rodriguez, 2024). Knowledge itself becomes a commodity, valued not for its capacity to enlighten or empower but for its capacity to reinforce global hierarchies.

Military and defense connections illustrate another dimension of complicity. ROTC programs, defense research contracts, and partnerships with intelligence agencies embed universities directly within state power and the machinery of imperial control. Students from working-class backgrounds may see military scholarships as pathways to mobility, yet these programs impose long-term obligations, exposure to systemic discrimination, and moral risk, binding individuals to structures that serve national and corporate interests rather than individual or public welfare (Johnson, 2024). By providing both material incentives and ideological framing, universities shape not only research and discourse but also life trajectories, often in ways that reproduce existing inequalities.

Technological developments exacerbate these trends. The rise of artificial intelligence in global education exemplifies digital neocolonialism, where Western frameworks dominate curricula and knowledge production, marginalizing non-Western epistemologies (Lee, 2024). Universities, in adopting and disseminating these technologies, participate in global systems that enforce cultural hegemony while presenting an illusion of neutrality or progress.

Critics argue that U.S. higher education’s complicity is most visible during crises abroad. In Venezuela, universities have hosted panels and research collaborations that echo dominant U.S. policy narratives, while largely ignoring humanitarian consequences (Higher Education Inquirer, 2025). During conflicts in Yemen and Gaza, partnerships with foreign institutions and the enforcement of donor or corporate agendas frequently coincide with silence on human rights abuses. Even when individual scholars attempt to challenge these norms, institutional pressures—funding dependencies, prestige incentives, and market logics—often constrain their capacity to act.

The structural nature of this complicity means that reform cannot be solely individual or performative. Transparency in funding, ethical scrutiny of partnerships, and protection for dissenting voices are necessary but insufficient. Universities must critically examine their embeddedness within global systems of extraction, surveillance, and domination. They must ask whether the pursuit of prestige, rankings, or revenue aligns with the purported mission of fostering equitable knowledge production. Only through systemic, structural change can institutions move from passive complicity toward active accountability.

The implications of these dynamics extend beyond academia. Universities train professionals, shape policy, and generate research that informs global decision-making. When they normalize inequality, silence dissent, or serve as instruments of state or corporate power, the consequences are felt in classrooms, clinics, policy offices, and across global societies. Students, researchers, and communities are both shaped by and subjected to these power structures, often in ways that perpetuate the very inequalities institutions claim to challenge.

In exposing these patterns, recent scholarship has provided both a theoretical and empirical foundation for critique. From analyses of academic capitalism and labor precarity (Slaughter & Rhoades, 2022) to examinations of global knowledge hierarchies (Smith & Rodriguez, 2024) and digital neocolonialism (Lee, 2024), researchers have mapped the pathways through which higher education reproduces systemic inequality. By integrating these insights, scholars, students, and policymakers can begin to imagine alternatives—universities that truly serve knowledge, equity, and global justice rather than empire and market logic.

Higher education’s promise has always been aspirational: the idea that knowledge might liberate rather than constrain, enlighten rather than exploit. Yet in the current landscape, universities often do the opposite, embedding global hierarchies within their governance, research, and pedagogical frameworks. Recognizing this complicity is the first step. Confronting it requires courage, structural awareness, and a commitment to justice that extends far beyond the walls of the academy.

References

-

Higher Education Inquirer. (2025). Higher Education and Its Complicity in U.S. Empire. https://www.highereducationinquirer.org/2025/11/higher-education-and-its-complicity-in.html

-

Jansen, J. (2024). The university in contemporary South Africa: Commodification, corporatisation, complicity, and crisis. Journal of Education and Society, 96, 15–34.

-

Johnson, M. (2024). The hidden costs of ROTC and military pathways. Higher Education Inquirer. https://www.highereducationinquirer.org/2025/11/the-hidden-costs-of-rotc-and-military.html

-

Lee, C. (2024). Generative AI and digital neocolonialism in global education: Towards an equitable framework. arXiv:2406.02966.

-

Slaughter, S., & Rhoades, G. (2022). Not in the Greater Good: Academic capitalism and faculty labor in higher education. Education Sciences, 12(12), 912.

-

Smith, R., & Rodriguez, L. (2024). The Howard‑Harvard Effect: Institutional reproduction of intersectional inequalities. arXiv:2402.04391.