For millions of Americans, tattoos were meant to be personal landmarks—bold, permanent declarations of identity. For college students, the decision to get one often happens in the whirlwind of new freedom, campus culture, and peer influence. But as years pass and the ink fades, many find themselves with more than just a physical reminder—they face a costly, time-consuming process of erasure.

The scale of regret is hard to ignore. Surveys suggest that about one in four Americans with tattoos regret at least one of them. That’s roughly 20 million people, and among those aged 18 to 30—prime college years—the number climbs closer to one in three. A dermatology study found that 26 percent of tattooed patients expressed regret, with over 40 percent of them seeking removal or cover-ups. Regret is especially common when tattoos are obtained in late adolescence, when judgment is less mature, or when they are done cheaply, hastily, or in highly visible areas like the forearms, neck, or face.

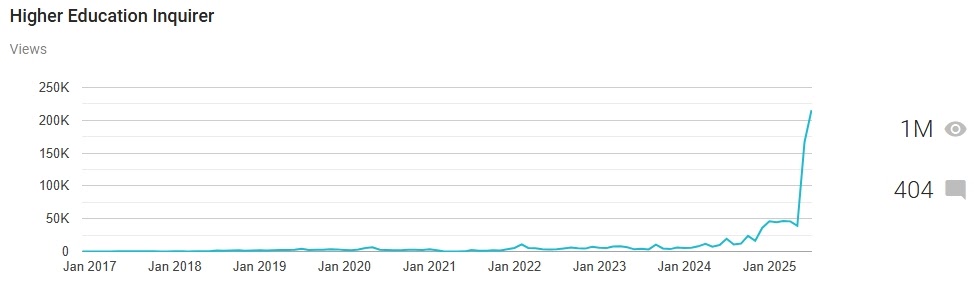

The economic fallout is familiar to anyone who has studied the for-profit college industry. Just as private lenders profit from the desperation of indebted graduates, the tattoo removal industry thrives on the emotional and professional consequences of youthful decisions. In 2024, the global tattoo removal market was worth more than $1.1 billion and is projected to triple by 2032. In the U.S., the market has ballooned from $65.9 million in 2023 to a forecast of more than $400 million by 2033. Clinics report surges in demand, with some chains—like Removery—expanding to over 150 locations worldwide. Their marketing often mirrors higher education’s own slogans of transformation and reinvention.

The drivers of removal are telling. A tattoo might commemorate a relationship that ended badly, reflect a political or cultural affiliation that’s become toxic, or simply be a relic of a passing trend. Others are driven to removal for professional survival. While tattoos have become more acceptable in creative fields and service work, they can still derail opportunities in education, law, finance, healthcare, and parts of the military. For some, removal is less about a paycheck and more about reclaiming a sense of self from a younger, more impulsive version of themselves.

What higher education often fails to admit is that it plays a role in this cycle. Universities spend heavily on branding campaigns that tell students to “make their mark,” “be fearless,” or “define your identity.” In campus environments where these messages blend with alcohol, peer pressure, and instant access to tattoo parlors, the permanence of a decision is rarely emphasized. Just as with signing loan papers, the cost comes later—often at a time when money is tight and options are few.

The irony is that both industries—higher education and tattoo removal—present themselves as pathways to a better self. One promises the power to transform your future; the other promises to erase your past. And in both cases, it is the young, the inexperienced, and the financially vulnerable who pay the highest price.

Tattoos are not inherently mistakes. They can be art, heritage, or deeply personal affirmations. But when permanence meets the fluid identity of early adulthood, the risk of regret is real. If universities truly see themselves as guiding students toward informed choices, they might start by being honest about the permanence—not just of ink, but of all life decisions made in the shadow of campus marketing campaigns.

Sources:

Fortune Business Insights, Tattoo Removal Market Size, Share, Trends (2024)

GQ, “Why Is Everyone Getting Their Tattoos Removed?” (2024)

WiFi Talents, Tattoo Regret Statistics (2024)

ZipDo, Tattoo Regret Statistics (2024)

NCBI, “Tattoo Removal and Regret: A Cross-Sectional Analysis” (2023)

Allied Market Research, Tattoo Removal Market (2024)

IMARC Group, Tattoo Removal Market Report (2024)

The Times (UK), “Confessions of the Tattoo Removers” (2024)

Herald Sun, “Why Tattoo Removal Is Soaring” (2024)