Undocumented students who grew up in the U.S. were allowed to pay in-state college tuition in roughly half of states. But now those benefits are under attack, and some states are walking back their policies, leaving thousands of students scrambling.

This summer, the U.S. Department of Justice sued three states—Kentucky, Minnesota and Texas—over laws that permit noncitizens who grew up in these states to pay the same rates as their peers.

In a shocking move, Texas sided with the federal government within hours of the first lawsuit in June, abruptly ending in-state tuition for noncitizens in the state. Now undocumented students in Texas and multiple civil rights groups are seeking to intervene and reopen the case. They argue Republican state lawmakers and the federal government colluded to reach a speedy resolution, and affected students didn’t get to have their day in court.

The defendants in the Kentucky case—Gov. Andy Beshear, Commissioner of Education Robbie Fletcher and the Kentucky Council on Postsecondary Education—have until mid-August to respond to an amended complaint from the DOJ. The Minnesota lawsuit has been assigned to a federal district judge. Gov. Tim Walz, Minnesota attorney general Keith Ellison and the Minnesota Office of Higher Education received a summons in late June.

The rash of lawsuits comes after President Donald Trump issued an executive order in April calling for a crackdown on sanctuary cities and state laws unlawfully “favoring aliens over any groups of American citizens,” citing in-state tuition benefits for noncitizens as an example. The recent DOJ lawsuits allege that these state laws favor undocumented students over American out-of-state students.

As these in-state tuition policies become a political flashpoint across the country, here’s what you need to know about them.

1. These laws are more than two decades old.

Texas became the first state to offer in-state tuition rates to certain undocumented students in 2001 when the Texas Dream Act was signed into law. California soon followed, enacting a similar law later that same year.

Currently, 23 states and the District of Columbia have such policies, according to the Higher Ed Immigration Portal. Another four states allow in-state tuition rates for noncitizens at some but not all public universities. And five states permit in-state tuition only for participants in the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program. For about a decade, Florida also allowed in-state tuition for undocumented students who met certain requirements, but the state rolled back the policy earlier this year.

2. They’ve historically been bipartisan.

While in-state tuition for noncitizens has become a politically polarizing issue, these policies historically enjoyed broad support from state lawmakers of both parties. Republican and Democratic advocates argued that helping undocumented students who attended local high schools go to college would set these students on career paths that benefit state economies. Opponents now argue these laws incentivize illegal immigration.

The Texas Dream Act was signed by Republican governor Rick Perry 24 years ago. He stood by the policy during his 2012 run for president, despite pushback.

“If you say that we should not educate children who come into our state for no other reason than that they’ve been brought there through no fault of their own, I don’t think you have a heart,” Perry said during a 2011 Republican primary debate. “We need to be educating these children because they will become a drag on our society.”

Perry opposed the federal DREAM Act, which would have created a pathway to citizenship, but advocated for in-state tuition decisions to be left up to states.

The author of Oklahoma’s in-state tuition law, enacted in 2007, was also a Republican lawmaker, Oklahoma representative Randy Terrill. His bill, which won bipartisan support in the state House and Senate, was signed into law by Democratic governor Brad Henry.

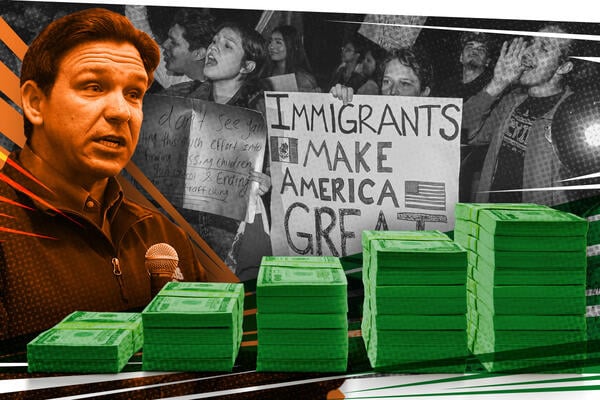

Florida Republican governor Rick Scott signed a similar law in 2014, which was scrapped as part of broader immigration legislation signed by Gov. Ron DeSantis earlier this year.

When asked about the prospect of the law’s repeal in 2023, Scott told The Florida Phoenix he was “proud” to have signed the bill and “would sign [it] again today.”

Other Republicans rescinded their support.

“It’s time to repeal this law,” Jeanette Nuñez, former lieutenant governor of Florida and current president of Florida International University, wrote on X shortly before the law’s demise. “It has served its purpose and run its course.”

3. Undocumented students must meet specific criteria in each state to qualify.

Each state law comes with different requirements, but undocumented students generally need to prove they’ve lived in a state for a significant amount of time and attended local high schools to qualify for in-state tuition benefits.

For example, in Oklahoma, noncitizens must have graduated from an Oklahoma high school and spent two years with a parent or guardian in the state while taking classes. They also must sign an affidavit promising to apply for legal status when able or show proof they’ve already petitioned U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services for legal status.

Undocumented students in Washington State must have spent their senior year at a local high school or earned a G.E.D. in the state, live in the state for at least three consecutive years, as of the date they graduated, and pledge to seek legal permanent residency as soon as legally possible.

4. The laws are designed to also apply to citizens.

These in-state tuition laws are typically crafted to offer in-state tuition rates to students who meet their specific criteria—regardless of immigration status.

That means, in California, for example, any nonresident who spent three years in California high schools is eligible for in-state tuition. So, the policy not only applies to undocumented students but also U.S. citizens who perhaps grew up in the state but may have left and returned for any reason.

Similarly, before the Texas law was dismantled, out-of-state students could gain residency and eligibility for in-state tuition if they graduated from a Texas high school and spent at least three years prior in the state. The policy benefited citizens born and raised in Texas whose parents moved out of the state before they enrolled in college, according to an amicus brief filed by the Intercultural Development Research Association in 2022, when the law faced a legal challenge from the Young Conservatives of Texas.

Advocates for these policies say that’s why they don’t violate the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996, which prohibits states from providing higher ed benefits to undocumented immigrants unless citizens are also eligible. Trump cited the federal statute in his executive order.

Over the years, these laws have been challenged multiple times in court, but until the DOJ’s lawsuit against Texas, none succeeded.