- By Ruth Arnold, Executive Director of External Affairs, Study Group and cofounder of the #WeAreInternational campaign

This weekend, an American president stood on the tarmac by Air Force One and took questions from reporters. One picked on his current legal confrontation with one of the world’s most famous universities and one older than the United States itself, Harvard.

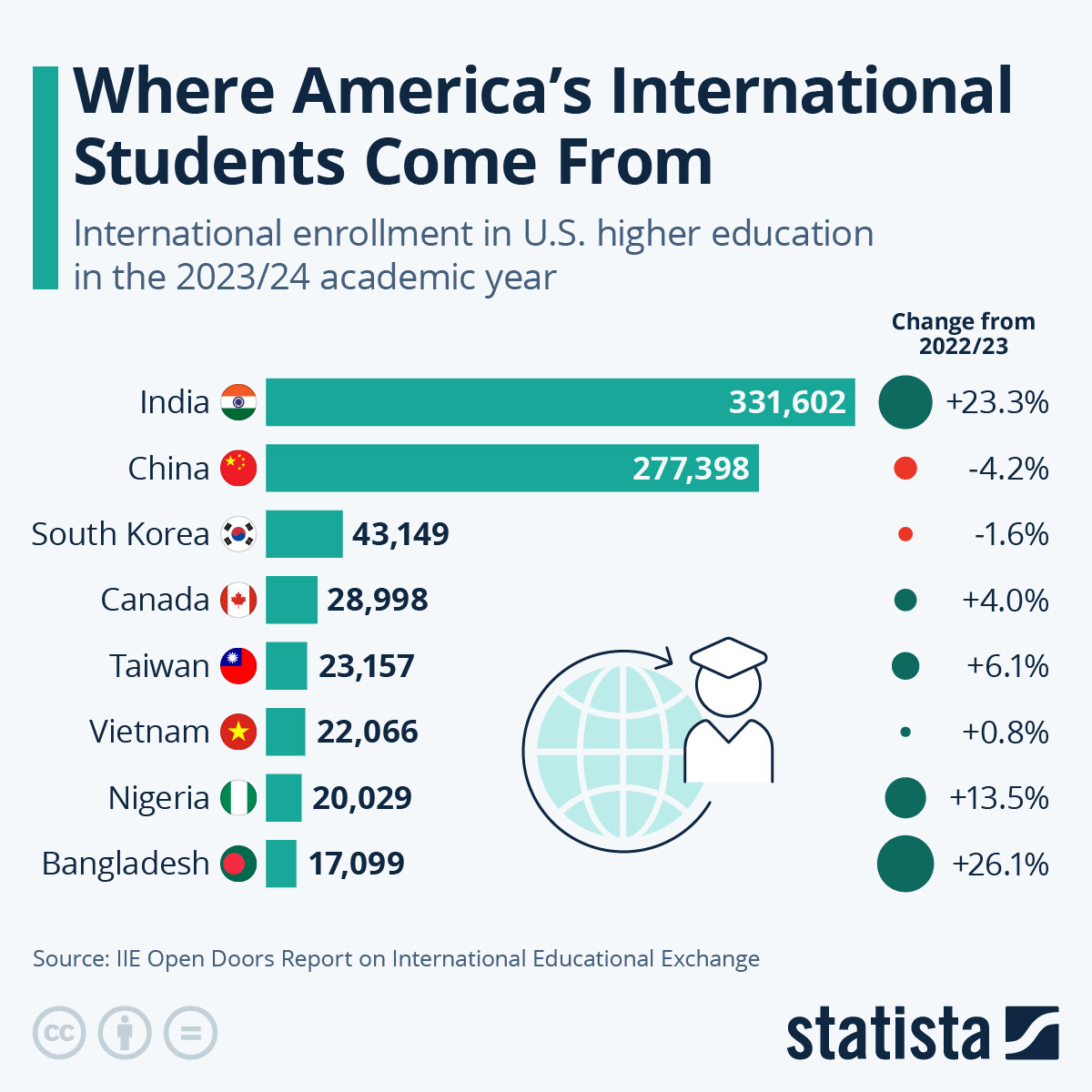

‘Part of the problem with Harvard,’ he said, ‘is they are almost 31% of foreigners coming to Harvard… it’s too much, because we have Americans that want to go there. No foreign government contributes money to Harvard. We do.’ Harvard’s single sentence response on X was clear, ‘Without its international students, Harvard is not Harvard.’ Within a day, the State Department had paused all US student visa appointments globally – affected students around the world immediately began rethinking their options.

Here in Britain, politics around international students has less of the overt drama of the US. Yet even as the Immigration White Paper stepped back at the eleventh hour from the most extreme measures to curtail the Graduate Visa, a link between efforts to reduce immigration statistics and to use student levers to do so is now explicit. British universities’ pride in reaching the government’s own target of 600,000 overseas students is no longer simply applauded as a success for regional economies, research capacity and soft power, but also seen as a contributor to political risk. And if we think political narratives in the US won’t travel across the Atlantic, we’ve not understood the world we now live in.

‘The Overseas Student Question’ – taking a long view of UK international education strategy

A few months ago, a friend gave me a book found in an Oxfam shop. Published in 1981 by the Overseas Student Trust, The Overseas Student Question: Studies for a Policy promised a fresh look at a growing debate – what were the costs and benefits of welcoming international students, the implications for foreign policy, the importance for ‘developing countries’ of study abroad? And what were the requirements of students themselves?

First, though, I wanted to understand who was behind this book. The Overseas Student Trust was founded in 1961 as an educational charity by a group of leading transnational companies, many of whom sponsored international students to come to the UK – Barclays, BP, ICI, Shell and Blue Circle amongst them. There had also been a companion report, Freedom to Study, and an earlier National Union of Students (NUS) survey called International Community?. I noted the ominous question mark in the title and a link to the founding of the UK Council for Overseas Student Affairs. The author and editor was Lord Carr of Hadley – a Conservative politician, pro-European former Home Secretary and such an able reformer that when Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister and didn’t offer him a role as Foreign Secretary, she chose not to offer him an alternative to avoid having such a capable opponent in her ranks.

Lord Carr began with a recognition of policy failure and a need to do better: ‘The overseas student question has generated more heat than light in the recent past and therefore nothing but good can come from a long, cool look at its various aspects.’ Then as now, nobody was clear where in government international student policy should sit. For 30 years it had been led by overseas departments of state, and delegated to the British Council they funded. Yet the policies which actually impacted students were found ‘in the Department of Education and Science in respect of tuition fees, and the Home Office as regards immigration and employment’.

There was also a shortage of reliable data to inform decisions, and it was nearly impossible to calculate their political or even trading benefits. These were ‘so far off in time that the link between cause and effect can scarcely be recognised, and the case for overseas students is thus the victim, because unfortunately in politics the short-term tends to preempt the long-term, and the urgent usurps the place of the important.’

So Lord Carr pulled in the heavyweights of his day to make a case for the value of international education to government. In addition to the Department of Trade and CBI, the Chairmen of more than forty of Britain’s largest exporters and firms with interests abroad wrote letters to make plain the importance to their future success of ‘the foreign national who has had some of his education in Britain’. Leading industrialists argued for ‘as large a population of international students as possible in the years ahead.’

Yet Lord Carr recognised a need for balance between national priorities and the preservation of institutional autonomy in the process of selection and admissions, and he had doubts about the ability of government to make such decisions alone. ‘These are not matters to be laid solely at government’s door. Industry and the educational world should be involved, both in the thinking and the implementation.’

The Labour beginnings of international cross-subsidy

The International Student Question was written at a point of inflection. In 1963, the Robbins Committee on Higher Education described subsidies to international students as a form of foreign aid, estimated to be £9 million for 20,000 students. In 1966 it was a Labour government that first announced a differential fee, £250 compared to £70 for home students, and in 1969 Shirley Williams argued for a more restrictive policy on international students.

All this led to a change in dynamic from self-interested charity to overt trade. So Lord Carr made a new plea for ‘careful thought about how we provide for overseas students once they have arrived in this country,’ noting that students were ‘no longer subsidised objects of charity’ but have become the purchasers of services at £5000 per year. He quoted the Chairman of ICI – ‘caring pays because overseas students will expect value for money.’

This is not to say international education had lost all ideals. Carr, a post-War Private Secretary to Anthony Eden, saw a greater prize – ‘The British experience must be seen in the wider context of the international mobility of students which is one of the foundation stones of a peaceful, stable and interdependent world.’

International Education Strategies Globally

Which brings us back to our own times, where questions of peace and interdependence through international mobility still matter.

The UK refresh of the International Education Strategy is now overdue, and it will no doubt focus heavily on national priorities, on growth and innovation, inward and outbound mobility, global partnerships, transnational provision and terminology beloved of the FCDO, ‘soft power’. And yet hard forces are at play. It isn’t just a question of global trade and avoiding conflict – we now live in a multipolar era in which former colonies and adversaries are the burgeoning economic powers of the future. Our government does not act in isolation or have the ability to control the choices made by sponsors, families and students a world away. While international education strategy is written in Whitehall, the forces that drive it in actuality are global.

Home thoughts from abroad

A few years ago, I gave evidence to a parliamentary committee considering the local economic impact of international students with the then mayor of South Yorkshire and now a Labour government minister, Dan Jarvis. It wasn’t difficult for Dan to say what an influx of cash meant to a region like ours or the importance of cross-subsidy to research collaboration with industry. On his doorstep was a major new research campus on the formerly derelict waste ground of Orgreave. Inspiration had come from a Vietnamese PhD student on placement in a struggling local manufacturing firm. Her insights addressed live problems and the company won multiple orders against global competition, securing jobs. South Yorkshire wanted more of this.

But what of that student’s home country? If we want our international education policies to reflect our own times rather than the age of Empire, we need take an interest in her side of the story too. Today, Vietnam is transformed from the war-torn nation that the student and her family had left behind. In common with much of ASEAN, it is now going through its own efforts to lift manufacturing capacity and transform its economy through research, education and high-value tech manufacturing. It’s got more in common with post-industrial S Yorkshire than many realise.

Today’s Vietnamese students travel to traditional study destinations, but global education is changing. Vietnam is keen to emulate the successes of Malaysia and Singapore as a major Asian education hub. The aim is for partnerships and an education system that will lift more of its young population and so transform its prospects. We might take our own lessons from that.

International education is increasingly seen as a key driver of global development. China and India, the two great source countries for traditional study destinations, are actively building their own domestic capacity. China invests 4% of its GDP in its universities, leading to a significant increase in research output, global rankings, and international collaborations, and it is now actively seeking to attract students and scholars from overseas, including through full and partial funding for undergraduate and postgraduate studies. Meanwhile, India’s growing reputation as a global education hub, coupled with initiatives like the ‘Study in India’ programme, is boosting its appeal. Fifteen foreign universities are opening campuses in India this year, including the Universities of Southampton and Liverpool.

The so-called Big Four study destinations – the UK, America, Canada and Australia are now increasingly seen as the Big Ten and counting. Korea, Japan, Malaysia and Thailand are seeing the possibilities to lift their own institutions and economies by persuading talent and investment to stay closer to home. The Middle East is pursuing similar aims. For many students, the lure of the West and its freedoms continues, but it is no longer the only aspirational option, whatever those countries’ International Education Strategies say.

In search of a double win

One of the great challenges across the world is youth unemployment and underemployment, including among graduates. As nations all compete to move up the value chain and labour markets navigate headwinds of trade restrictions and AI disruption, old certainties about returns on higher education are taking a hit.

International Education Strategies need to find a sweet spot, and the UK government is aiming for just that. One that meets both national and international needs and desires, which lifts local communities and sustains universities, while equipping intrepid young people across the world with the degrees and cultural agility that comes from living and working overseas, fluent in what is still the dominant language of global commerce and much innovation.

The challenge for the International Education Strategy and its authors is to speak to more than their own ministers and domestic audiences. We should learn from the US. The news of an immediate threat to revoke international student visas at Harvard made its way around the world within hours. Universities in Hong Kong, China and Malaysia offered unconditional offers to ‘Harvard refugees’, a term worried international students had themselves used on social media. The UK has form here too. Negative rhetoric and the loss of post-study work led to a calamitous fall in international students and a brutal loss of trust. We don’t want to go back to that.

What we need now is something better. A strategy which acknowledges both sides of an equation, what is right for the home nation, but also improves the lives and opportunities of students from around the world. Lord Carr was right. At a time of global change and complexity, knowledge and those who seek and add to it cannot be contained behind borders. The next British International Education Strategy should honour and do right by all who contribute to global education, our students and our academics. It should enable our universities to play a full part in both the success of their own communities and of the world. This is not a matter of funding alone, but of education and identity. Let’s hope it succeeds. After all, higher education is not an island; we are international.