by Jeni Hebert-Beirne, The Hechinger Report

December 22, 2025

It started with Harvard University. Then Notre Dame, Cornell, Ohio State University and the University of Michigan.

Colleges are racing to close or rename their diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) offices, which serve as the institutional infrastructure to ensure fair opportunity and conditions for all. The pace is disorienting and getting worse: since last January, 181 colleges in all.

Often this comes with a formal announcement via mass email, whispering a watered-down name change that implies: “There is nothing to see here. The work will remain the same.” But renaming the offices is something to see, and it changes the work that can be done.

Colleges say the changes are needed to comply with last January’s White House executive orders to end “wasteful government DEI programs” and “illegal discrimination” and restore “merit-based opportunity,” prompting them to replace DEI with words like engagement, culture, community, opportunity and belonging.

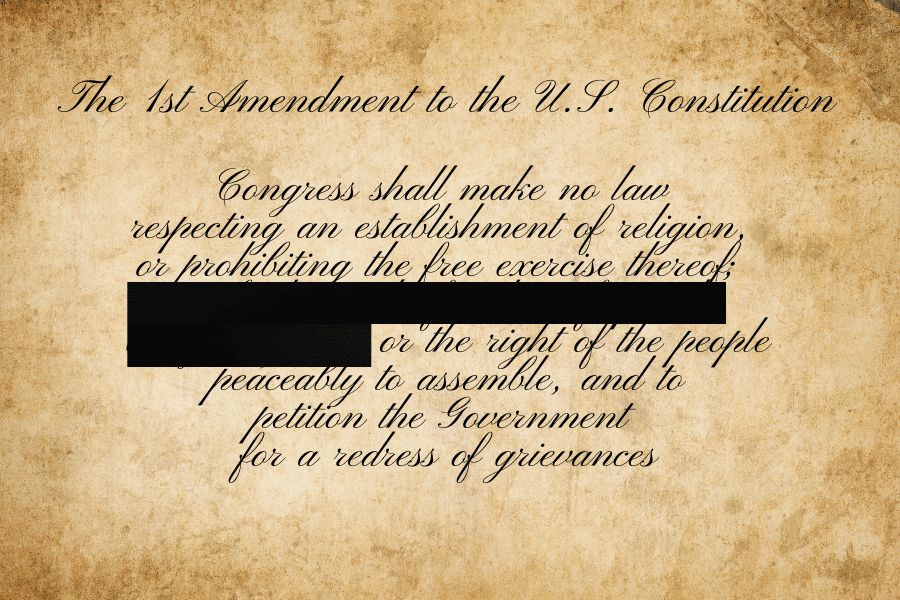

One college went even further this month: The University of Alabama ended two student-run magazines because administrators perceived them to be targeting specific demographics and thus to be out of compliance with Attorney General Pamela Bondi’s anti-discrimination guidance. Students are fighting back while some experts say the move is a blatant violation of the First Amendment.

Related: Interested in innovations in higher education? Subscribe to our free biweekly higher education newsletter.

With the one-year mark of the original disruptive executive orders approaching, the pattern of response is nearly always the same. Announcements of name changes are followed quickly by impassioned pronouncements that schools should “remain committed to our long-standing social justice mission.”

University administrators, faculty, students, supporters and alumni need to stand up and call attention to the risks of this widespread renaming.

True, there are risks to not complying. The U.S. State Department recently proposed to cut research funding to 38 elite universities in a public-private partnership for what the Trump administration perceived as DEI hiring practices. Universities removed from the partnership will be replaced by schools that the administration perceives to be more merit-based, such as Liberty University and Brigham Young University.

In addition to the freezing of critical research dollars, universities are being fined millions of dollars for hiring practices that use an equity lens — even though those practices are merit-based and ensure that all candidates are fairly evaluated.

Northwestern University recently paid $75 million to have research funding that had already been approved restored, while Columbia University paid $200 million. Make no mistake: This is extortion.

Some top university administrators have resigned under this pressure. Others seem to be deciding that changing the name of their equity office is cheaper than being extorted.

Many are clinging to the misguided notion that the name changes do not mean they are any less committed to their equity and justice-oriented missions.

As a long-standing faculty member of a major public university, I find this alarming. In what way does backing away from critical, specific language advance social justice missions?

In ceding ground on critical infrastructure that centers justice, the universities that are caving are violating a number of historian and author Timothy Snyder’s 20 lessons from the 20th century for fighting tyranny.

The first lesson is: “Do not obey in advance.” Many of these changes are not required. Rather, universities are making decisions to comply in advance in order to avoid potential future conflicts.

The second is: “Defend institutions.” The name changes and reorganizations convey that this infrastructure is not foundational to university work.

What Snyder doesn’t warn about is the loss of critical words that frame justice work.

The swift dismantling of the infrastructures that had been advancing social justice goals, especially those secured during the recent responses to racial injustice in the United States and the global pandemic, has been breathtaking.

Related: Trump administration cuts canceled this college student’s career start in politics

This is personal to me. Over the 15 years since I was hired as a professor and community health equity researcher at Chicago’s only public research institution, the university deepened its commitment to social justice by investing resources to address systemic inequities.

Directors were named, staff members hired. Missions were carefully curated. Funding mechanisms were announced to encourage work at the intersections of the roots of injustices. Award mechanisms were carefully worded to describe what excellence looks like in social justice work.

Now, one by one, this infrastructure is being deconstructed.

The University of Illinois Chicago leadership recently announced that the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Equity and Diversity will be renamed and reoriented as the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Engagement. The explanation noted that this change reflects a narrowed dual focus: engaging internally within the university community and externally with the City of Chicago.

This concept of university engagement efforts as two sides of one coin oversimplifies the complexity of the authentic, reciprocal relationship development required by the university to achieve equity goals.

As a community engagement scientist, I feel a major loss and unsettling alarm from the renaming of “Equity and Diversity” as “Engagement.” I’ve spent two decades doing justice-centered, community-based participatory research in Chicago neighborhoods with community members. It is doubtful that the work can remain authentic if administrators can’t stand up enough to keep the name.

As a professor of public health, I train graduate students on the importance of language and naming. For example, people in low-income neighborhoods are not inherently “at risk” for poor health but rather are exposed to conditions that impact their risk level and defy health equity. Health is “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being,” while health equity is “the state in which everyone has the chance to attain full health potential.” Changing the emphasis from health equity to health focuses the system’s lens on the individual and mutes population impact.

Similarly, changing the language around DEI offices is a huge deal. It is the beginning of the end. Pretending it is not is complicity.

Jeni Hebert-Beirne is a professor of Community Health Sciences at the University of Illinois Chicago School of Public Health and a public voices fellow of The OpEd Project.

Contact the opinion editor at [email protected].

This story about colleges and DEI was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s weekly newsletter.

This <a target=”_blank” href=”https://hechingerreport.org/opinion-colleges-are-not-just-saying-goodbye-to-dei-offices-they-are-dismantling-programs-that-assure-institutional-commitment-to-justice/”>article</a> first appeared on <a target=”_blank” href=”https://hechingerreport.org”>The Hechinger Report</a> and is republished here under a <a target=”_blank” href=”https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/”>Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License</a>.<img src=”https://i0.wp.com/hechingerreport.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/cropped-favicon.jpg?fit=150%2C150&ssl=1″ style=”width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;”>

<img id=”republication-tracker-tool-source” src=”https://hechingerreport.org/?republication-pixel=true&post=114031&ga4=G-03KPHXDF3H” style=”width:1px;height:1px;”><script> PARSELY = { autotrack: false, onload: function() { PARSELY.beacon.trackPageView({ url: “https://hechingerreport.org/opinion-colleges-are-not-just-saying-goodbye-to-dei-offices-they-are-dismantling-programs-that-assure-institutional-commitment-to-justice/”, urlref: window.location.href }); } } </script> <script id=”parsely-cfg” src=”//cdn.parsely.com/keys/hechingerreport.org/p.js”></script>