This blog was kindly authored by John Claughton, Co-Founder of The World of Languages and Languages of the World and former Chief Master of King Edward’s School, Birmingham.

The other day, there was a big crowd packed into the Attlee Room in Portcullis House to celebrate the European Day of Languages – it was a comfort that no one had deemed it necessary to wear a sombrero or lederhosen. It was a co-production by the All Party Parliamentary Group for Languages and the All Party Parliamentary Group for Europe. The French and EU Ambassadors to London were the guests of honour, and the meeting was chaired by that rara avis, Darren Paffey, an MP who had been a languages academic. And he even has a wife who teaches languages. Is there, after all, a candle of hope for us all?

The event was, like Gaul, divided into three parts. The first part was the noble land of diplomacy, with emphasis on the need for mutual understanding, co-operation and mobility in pursuit of global prosperity and harmony. At least everyone agreed that it was time for Erasmus to return – the programme, not the author of In Praise of Folly.

Part Two was less to do with the noble sentiments of the Republic of Plato than the sewers of Romulus. It was about the grim facts of language learning presented by Megan Bowler, the harbinger of darkness, who wrote the HEPI report on the ‘language crisis’:

- only 3% of A-level entries are in languages, and a mighty slug of those would come from independent schools;

- undergraduate enrolments in languages are down by 20% in five years;

- language teacher recruitment is less than half of what it needs to be;

- there would still be language teacher shortages if every languages graduate went into teaching.

- 28 out of 38 post-1992 universities have closed their language departments:

- it is now quite common for Oxbridge colleges to get fewer than 10 applicants each for languages. That’s less than Classics, by Jove.

Nor did the recent announcement about the end of IB funding bring any cheer: after all, every IB pupil has to study a language between the ages of 16 to 18.

After the cold wind of reality had blown through the room, Vicky Gough, the Schools Adviser at the British Council, and Bernardette Holmes, the Director of the National College for Language Education (NCLE), talked of the tracks across this bleak terrain which might lead to better days. The HEPI report itself makes ten recommendations, and there are clearly things that universities can do to make languages more appealing – ‘Bring back Erasmus,’ they cry. However, the future of languages in university cannot lie in the hands of universities. The landscape can only be changed by a fundamental rethink about the teaching of languages at the very beginning of this journey. And that rethink has to reflect the fundamental change that has taken place in the pupils who now sit in our classes. Here are some ‘facts’ which show that fundamental change:

- 20% of primary school pupils are categorised as EAL, i.e. English is not their first language;

- this figure materially understates the percentage of pupils who are multilingual in our schools: for example, I know that over 50% of the pupils in the school where I was head were bilingual, even though none of them were categorised as EAL.

- in many areas of many of our cities, there are primary schools where 90% of pupils are classed as EAL pupils.

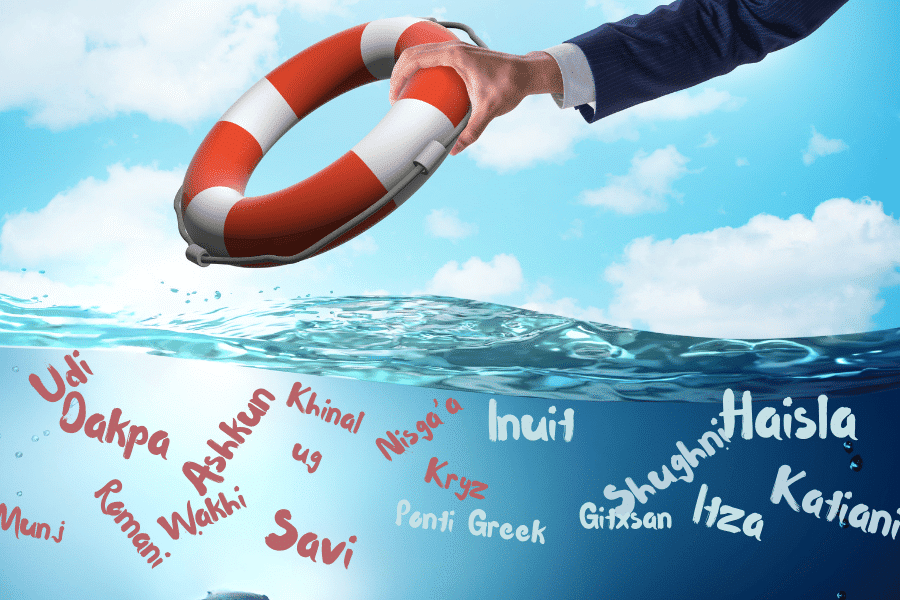

- there are many, many schools in London, or Birmingham, or Leicester, or Bradford where 30, or 40, or even 50 languages are spoken.

- the schools with the greatest linguistic diversity are very often the schools in the most disadvantaged areas, areas where language uptake is at its lowest.

And yet, little or no attention, or regard or honour is given to these languages, or to the pupils that speak them. Instead, in 96% of primary schools, it is French or Spanish which is taught, often by primary school teachers who don’t even have a GCSE in the subject. It may be no surprise that too few pupils arrive keen to study a language at GCSE when their language experience has been limited and, to their already multilingual minds, irrelevant.

So, if there is to be progress, if there is to be a halt in the decline in languages and in the regard for languages, the answer may not lie in doing a bit better what we have always done, but in doing something different. If primary school pupils were taught not French and Spanish, but about languages, their own languages, as well as English and ‘modern foreign languages’ – and even Latin – the following things might happen:

- pupils might see that languages are relevant, interesting, valuable, even fun;

- pupils might learn more about themselves and each other, engendering mutual understanding and respect;

- pupils might feel that they belong in school, and feel that there is not so great a gap between their life at home and their life at school;

- parents might feel that what was going on at school had some regard for their history and their culture;

- pupils might be more inclined to study languages, whether their own family/heritage language, and this could be a massive asset for their futures, in human and economic terms;

- and, as these young people grow up, they might become the kind of adults who can build an integrated, cohesive, respectful and diverse society, and thus silence the voices of division in our political debate.

- and this approach would demolish the hierarchy of languages which has so beset us for so long.

Thus, it would place languages at the heart of our society. That would be nice, wouldn’t it? By strange chance, I have been working with some colleagues for several years to create a programme that does just that, but I’ve reached my word limit.

But wait, dear reader. As a special dispensation, I have been granted more words in a HEPI blog. O frabjous day. So, I’d better be quick. It’s called WoLLoW, World of Languages, Languages of the World, a brilliant palindromic acronym with an Egyptian faience hippopotamus as a logo – just look at all those Greek words – in honour of the Hippopotamus Song by Flanders and Swan. So, if that’s its wondrous name, what does it do? Well, here are some examples:

- a WoLLoW lesson can encourage boys and girls to talk about their own language, their own family, their own history.

- it can explore why and how English is the most mongrel of all languages, a dog’s breakfast of Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, Viking, Norman French, and polysyllabic Graeco-Latin inventions.

- it can prove that the pupils can learn the Greek alphabet more quickly than their teachers, and thereby discover why physics isn’t spelt fisiks and dinosaurs have such preposterous names.

- it can ask why Tuesday is Tuesday here and lots of different things everywhere else – and a WoLLoW lesson might even ask why there are seven days in a week.

- in a WoLLoW lesson pupils can learn braille and/or sign-language, or even create their own language.

This looks quite good fun, and it turns out that it is. Another word limit looms, but I can say that it not only cheers up pupils but it also has an impact on those who teach it. The last of my words must go to a pupil at my old school, a Malaysian Muslim, who, whilst in Year 11, taught WoLLoW in a local, Birmingham primary school:

Working on these lessons, from the very first session, has not only given the children we have taught the opportunity to have their languages and cultures represented in class discussions, but has also allowed me to reconnect with my language and feel more confident in reclaiming it as a part of who I am. I am someone who, like, I suspect, a lot of the children we have taught, has felt disconnected from his language for a long time, and has been given the chance to once again put it front and centre and find their sense of self within it again.

The rest is silence.