Last week, Instructure, which owns the widely used learning management system Canvas, announced a partnership with OpenAI to integrate into the platform native AI tools and agents, including those that help with grading, scheduling, generating rubrics and summarizing discussion posts.

The two companies, which have not disclosed the value of the deal, are also working together to embed large language models into Canvas through a feature called IgniteAI. It will work with an institution’s existing enterprise subscription to LLMs such as Anthropic’s Claude or OpenAI’s ChatGPT, allowing instructors to create custom LLM-enabled assignments. They’ll be able to tell the model how to interact with students—and even evaluate those interactions—and what it should look for to assess student learning. According to Instructure, any student information submitted through Canvas will remain private and won’t be shared with OpenAI.

Steve Daly, CEO of Instructure, touted Canvas’s AI push as “a significant step forward for the education community as we continuously amplify the learning experience and improve student outcomes.” But many faculty aren’t convinced that integrating AI into every facet of teaching and learning is the answer to improving the function and value of higher education.

“Our first job is to help faculty understand how students are using AI and how it’s changing the nature of thinking and work. The tools will be secondary,” said José Antonio Bowen, senior fellow at the American Association of Colleges and Universities and co-author of the book Teaching With AI: A Practical Guide to a New Era of Human Learning. “The LMS might make it easier, but giving people a couple of extra buttons isn’t going to substitute for training faculty to build AI into their assignments in the right way—where students use AI but are still learning.”

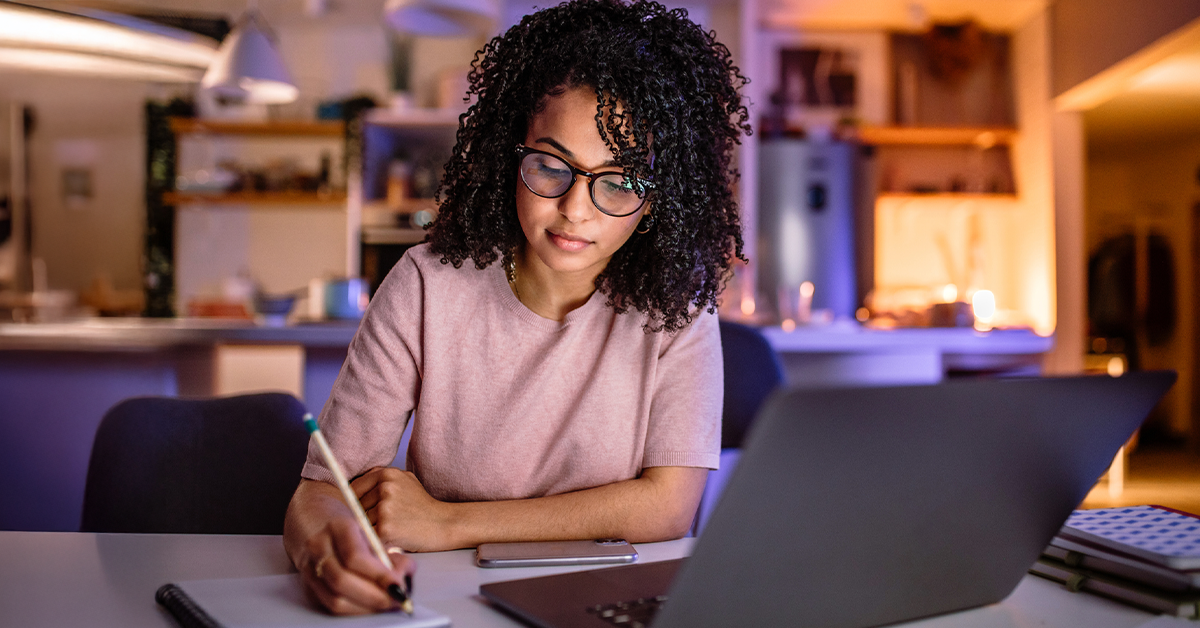

The AI-ification of Canvas is just one of the latest examples of the technology’s infiltration of higher education amid predictions that the technology will reshape and shrink the job market for new college graduates.

Earlier this year, the California State University system announced a partnership with a slate of tech companies—including Microsoft, OpenAI and Google—to give all students and faculty access to AI-powered tools, in part to equip students with the AI skills employers say they want. In April, Anthropic unveiled Claude for Education, which it designed specifically for college students. One day later, OpenAI gave college students free access to ChatGPT Plus through finals. Soon after, Ohio State University launched an initiative aimed at making every graduate AI “fluent” by 2029. And this week, OpenAI released Study Mode, a version of ChatGPT designed for college students that acts as a tutor rather than an answer generator.

Faculty Unsurprised, Skeptical

Few faculty were surprised by the Canvas-OpenAI partnership announcement, though many are reserving judgment until they see how the first year of using it works in practice.

“It was only a matter of time before something like this happened with one of the major learning management systems,” said Derek Bruff, associate director of the Center for Teaching Excellence at the University of Virginia. “Some of the use cases they’ve talked about make sense to me and others make less sense.”

Having Canvas provide a summary of students’ discussion posts could be a helpful time saver, especially for a larger class, though it doesn’t seem like “a game-changer,” he said. But he’s less sure that using the chat bot to evaluate student interactions, as Instructure suggests, could provide faculty with useful learning metrics.

“If students know that their interactions with the chat bot are going to be evaluated by the chat bot and then perhaps scored and graded by the instructor, now you’re in a testing environment and student behavior is going to change,” Bruff said. “You’re not going to get the same kind of insight into student questions or perspective, because they’re going to self-censor.”

Faculty, including the thousands who work for the more than 40 percent of higher ed institutions across North America that use Canvas, will have the option to use some or all of these new tools, which Instructure says it won’t charge extra for.

Those who choose to use it run the risk of “digital reification,” or “locking faculty and students into particular tools and systems that may not be the best fit for their educational goals,” Kathryn Conrad, an English professor at the University of Kansas who researches culture and technology, said in an email. “What works best for student learning is challenge, care and attention from human teachers. Drivers from outside of education are pushing yet another technological solution. We need investment in people.”

But as higher education budgets keep shrinking, faculty workloads are growing—and so is the temptation to use AI to help alleviate it.

“I worry about the people who are living out of their car, teaching at three institutions, trying to make ends meet. Why wouldn’t they take advantage of a system like Canvas to help with their grading?” said Lew Ludwig, a math professor and former director of the Center for Learning and Teaching at Denison University. “All of a sudden AI is going to be grading the work if we’re not careful.”

But that realization could push students to rely more and more on generative AI to complete their coursework without fully grasping the material—and give cash-strapped administrators another justification to increase faculty workloads. Such scenarios run the risk of further devaluing a higher education system that’s already facing scrutiny from lawmakers and consumers.

“Students are starting to graduate into a new economy, where just having a piece of paper hanging on their wall isn’t going to mean as much anymore, especially if they leaned heavily on AI to achieve that piece of paper,” Ludwig said. “We have to make sure our assignments are impactful and meaningful and that our students understand why in some instances we may not want them to use AI.”

Despite Instructure’s claims that this new version of Canvas will enhance the learning process in the age of AI, a recent survey by the American Association of University Professors shows that most faculty don’t believe AI tools are making their jobs easier; 69 percent said it hurts student success.

Britt Paris, co-author of the report and associate professor of library and information science at Rutgers University, said she doesn’t expect that to change with the introduction of an AI-powered LMS.

“In the history of educational technology there has never been an instance of large-scale … data-intensive corporate learning infrastructure that has met the needs of learners,” she said. “This is because people are nuanced in how they learn. The goal with these technologies is to make money, not [to] support people’s unique learning, teaching and working styles.”