For the first time in more than a decade, confidence in the nation’s colleges and universities is rising. Forty-two percent of Americans now say they have “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in higher education, up from 36 percent last year.

It’s a welcome shift, but it’s certainly not time for institutions to take a victory lap.

For years, persistent concerns about rising tuition, student debt and an uncertain job market have led many to question whether college was still worth the cost. Headlines have routinely spotlighted graduates who are underemployed, overwhelmed or unsure how to translate their degrees into careers.

With the rapid rise of AI reshaping entry-level hiring, those doubts are only going to intensify. Politicians, pundits and anxious parents are already asking: Why aren’t students better prepared for the real world?

But the conversation is broken, and the framing is far too simplistic. The real question isn’t whether college prepares students for careers. It’s how. And the “how” is more complex, personal and misunderstood than most people realize.

Related: Interested in innovations in higher education? Subscribe to our free biweekly higher education newsletter.

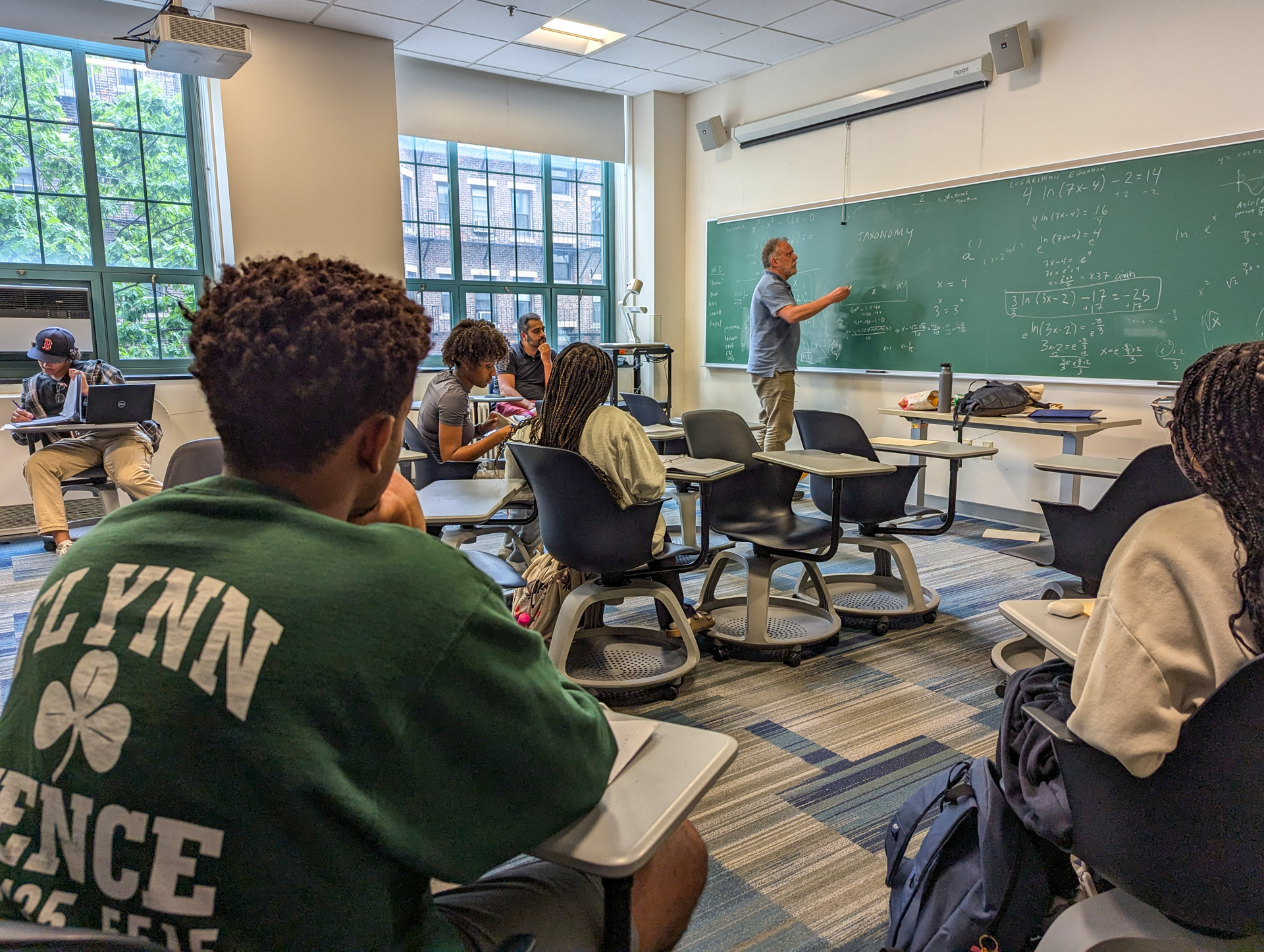

What’s missing from this conversation is a clearer understanding of where career preparation actually happens. It’s not confined to the classroom or the career center. It unfolds in the everyday often overlooked experiences that shape how students learn, lead and build confidence.

While earning a degree is important, it’s not enough. Students need a better map for navigating college. They need to know from day one that half the value of their experience will come from what they do outside the classroom.

To rebuild America’s trust, colleges must point beyond course catalogs and job placement rates. They need to understand how students actually spend their time in college. And they need to understand what those experiences teach them.

Ask someone thriving in their career which part of college most shaped their success, and their answer might surprise you. (I had this experience recently at a dinner with a dozen impressive philanthropic, tech and advocacy leaders.) You might expect them to name a major, a key class or an internship. But they’re more likely to mention running the student newspaper, leading a sorority, conducting undergraduate research, serving in student government or joining the debate team.

Such activities aren’t extracurriculars. They are career-curriculars. They’re the proving grounds where students build real-world skills, grow professional networks and gain confidence to navigate complexity. But most people don’t discuss these experiences until they’re asked about them.

Over time, institutions have created a false divide. The classroom is seen as the domain of learning, and career services is seen as the domain of workforce preparation. But this overlooks an important part of the undergraduate experience: everything in between.

The vast middle of campus life — clubs, competitions, mentorship, leadership roles, part-time jobs and collaborative projects — is where learning becomes doing. It’s where students take risks, test ideas and develop the communication, teamwork and problem-solving skills that employers need.

This oversight has made career services a stand-in for something much bigger. Career services should serve as an essential safety net for students who didn’t or couldn’t fully engage in campus life, but not as the launchpad we often imagine it to be.

Related: OPINION: College is worth it for most students, but its benefits are not equitable

We also need to confront a harder truth: Many students enter college assuming success after college is a given. Students are often told that going to college leads to success. They are rarely told, however, what that journey actually requires. They believe knowledge will be poured into them and that jobs will magically appear once the diploma is in hand. And for good reason, we’ve told them as much.

But college isn’t a vending machine. You can’t insert tuition and expect a job to roll out. Instead, it’s a platform, a laboratory and a proving ground. It requires students to extract value through effort, initiative and exploration, especially outside the classroom.

The credential matters, but it’s not the whole story. A degree can open doors, but it won’t define a career. It’s the skills students build, the relationships they form and the challenges they take on along the way to graduation that shape their future.

As more college leaders rightfully focus on the college-to-career transition, colleges must broadcast that while career services plays a helpful role, students themselves are the primary drivers of their future. But to be clear, colleges bear a grave responsibility here. It’s on us to reinforce the idea that learning occurs everywhere on campus, that the most powerful career preparation comes from doing, not just studying. It’s also on us to address college affordability, so that students have the time to participate in campus life, and to ensure that on-campus jobs are meaningful learning experiences.

Higher education can’t afford public confidence to dip again. The value of college isn’t missing. We’re just not looking in the right place.

Bridget Burns is the founding CEO of the University Innovation Alliance (UIA), a nationally recognized consortium of 19 public research universities driving student success innovation for nearly 600,000 students.

Contact the opinion editor at [email protected].

This story about college experiences was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s weekly newsletter.