Do you know which country emits the most greenhouse gases per capita? If not, you aren’t alone.

I’m a student at The Climate Academy, an international organization founded by philosopher and climate activist Matthew Pye who teaches students about climate change from a systems point of view.

This year, we surveyed almost 500 people in Brussels, Varese and Milan to analyse the level of climate literacy among populations across Europe. Many people we surveyed pointed at large emitters such as the United States, China and India.

Yes, these are big emitters in quantity, but when it comes to per capita emissions — the amount divided by the population of the country — the top three are smaller, wealthy countries: Singapore, the United Arab Emirates and Belgium.

These numbers can be explained by the extremely consumeristic, luxury lifestyle of the overwhelming majority of their citizens and the over-reliance on fossil fuels for generating energy. Yet, in our survey, 378 people out of 468 — 81% — named the United States, China or India.

What does this mean? That the media attention is on the wrong players. As stated by the World Economic Forum:

“When India surpassed the European Union in total annual greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2019 becoming the third largest emitting country after China and the United States, that statistic only told part of the story. India’s population is nearly three times larger than that of the EU, so based on emissions per person, India ranks much lower among the world’s national emitters.”

It is crucial to look at per capita emissions. That’s the conclusion of the Global Change Data Lab, a nonprofit organization that produces Our World in Data. It argues that annual national emissions do not take population size into account.

“All else being equal, we might expect that a country with more people would have higher emissions,” it reported. “Emissions per person are often seen as a fairer way of comparing. Historically — and as is still true in low- and middle-income countries today — CO2 emissions and incomes have been tightly coupled. That means that low per capita emissions have been an indicator of low incomes and high poverty levels.”

Europe often points at big emitters, but the comfortable lifestyles Europeans have due to their higher living standards aren’t sustainable.

There’s a misconception that the more a country emits, the more responsible the country is for climate change.

This is the result of intense lobbying and voluntary misdirection by the richest. The wealthiest individuals are undoubtedly responsible for a considerably higher share of global emissions. But we’re often told that countries like China and India are the most responsible, as they are some of the world’s biggest polluters, a fact which is widely recognized.

Pye said it isn’t a surprise that the focus is on numbers at the macro level, as international organizations like the United Nations were created by the main global powers and they are still funded mainly by them.

“Keeping the language and the numbers about the problem general and global masks the fact that the majority of our [per capita] emissions are still from these rich nations,” he said. “This lack of clarity about who is responsible is reflected right across global media coverage. It is not by chance that we don’t have a clear view of the vital statistics, it is by subtle and powerful design.”

The UN is founded on the principle of human rights, he said.

“Should it not think and act on climate change with everyone having an equal right to the air?” Pye said. “When you look at per capita and consumption emissions the whole landscape of responsibility is radically different.”

I conducted my part of the survey in a middle-class neighborhood of Brussels.

When I asked a 20-year-old, “What would the consequences of a two degree increase in global temperature be?” I got this answer: “More meteorites.” When I put the same question to someone 50 years of age, the answer was, “It’s going to be cold.”

A 75-year old told me: “I don’t believe in climate change. There were examples of extreme heat in the 17th century, it is natural. Climate change is a tool of the government to control us.”

All of these are misconceptions about weather events, temperature patterns and the source and type of climate change we experience.

Now, this survey included only a small sample of the population. But it already shows that the misconceptions in education about climate change are real and existent across every generation and in many ways. Many other surveys made by reputable organizations have supported this conclusion.

A 2010 report by the Yale University Program on Climate Change Education found that 63% of Americans believed that global warming was happening, but many did not understand why. In this assessment, only 8% of Americans had knowledge equivalent to an A or B, 40% would receive a C or D, and 52% would get an F.

A report by King’s College in London, based on a 2019 survey, found a similar level of ignorance.

Misconceptions are still here, waiting to be tackled. It starts in schools, where new, fresh generations without bias or misconceptions are formed. It starts at home, where parents should adapt and teach their kids the basics. Proper educational programs should be set up by governments.

This seems natural. But just a few months ago, in the United States, the Trump administration cut funding for schools that hold educational programs on climate change and greenhouse gas emissions reduction.

Educational systems, too, spread misconceptions about climate change. Because we never stop learning, educational systems shouldn’t have such flaws and should provide accurate information.

As we dive deeper into the climate crisis, proper knowledge and understanding will be key to systemic change and governmental response.

Until information on climate change becomes a public good, we will continue to “debate what kind of swimming costume we will wear as the tsunami comes.” Those are the words of then-U.S. Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson before the 2008 financial crisis.

1. Why is it important to consider the size of a population when considering responsibility for climate change?

2. What is meant by “climate ignorance”?

3. How can you learn more about climate change?

There’s any number of stories that can be told from UCAS’ sector level end of cycle data release.

UCAS itself, for instance, focuses on the new data on student residence intentions – 31 per cent of 18 year old applicants in 2025 intend to live at home (rising to 46 per cent in Scotland).

If we add in information on deprivation (IMD) and acceptance route, we learn that 50 per cent of the less advantaged quintile of students aged 18 intend to live at home while studying, compared to just 18 per cent of their peers in quintile 5.

And there are interesting regional variations – two thirds of the least advantaged 18 year old accepted applicants in Scotland intend to live at home (mouse over the map to see the regional breakdowns – and of course UK wide IMD isn’t a thing so treat that as indicative only).

Likewise, 75 per cent of the least advantaged group applying via main scheme Clearing will be living at home.

But you know and I know there has only been one recruitment story this year, and it is one that is best described via a very familiar chart:

Higher tariff (what we once called “selective”) providers are recruiting more 18 year old students than ever before, a trend that has become more prominent since the end of pandemic restrictions. The chart above shows acceptance rates, demonstrating that – simply put – as an 18 year old you are now substantially more likely to end up at a high tariff provider if you apply there.

One of the commonly proposed explanations for this phenomenon is the way in which applicants are using the “decline my place” functionality (on the UCAS platform since 2019) to trade up to a more prestigious provider. But the data neatly disproves this – movement tends to be within rather than between tariff bands:

We also get data by tariff group and acceptance route in this release – and from that we can see some very interesting underlying trends. Here the thick bars are the proportions and the thin ones the raw numbers, with the colours showing acceptance routes.

Gradually higher tariff providers have been taking a lower proportion of their 18 year old students via firm acceptances, and a higher proportion from other main scheme choices (including clearing). But this shift needs to be set against enormous expansion in numbers across the board – high tariff providers took more 18 year olds overall this year than their entire 2019 intake, and more firm or insurance 18 year old applicants this year than their entire 2023 intake.

In contrast, proportions of 18 year olds by route have stayed broadly similar by proportion in medium and low providers, with medium tariff numbers staying steady and low tariff numbers slowly falling.

So, even though high tariff providers have been slightly more active in clearing than in recent years (and even then, it is not outside of historic proportions) the growth comes simply from making offers to more applicants who apply to them, and then accepting them.

What I really wanted to know is on what terms. There’s already a fair amount of circumstantial evidence that high-tariff providers are making low tariff offers – and I was hoping that this release would give us the data we needed to be sure.

But UCAS has always been very coy about the association between tariff groups and the actual grades they accept. I can kind of understand the commercial in confidence arguments about detailed data at provider level (but the more I think about it the less I do…) – I cannot see any reason why we are not allowed to see grades by tariff group.

So I am taking a roundabout route using the data we have got, and we start by looking at the relationship between achieved A level points and POLAR4 quintiles. I’ve generally held the opinion that A levels are a fantastic way of telling how middle class an 18 year old applicant is so there are no surprises that people from better off background are more likely to apply, more likely to be accepted if they apply, and more likely to have better grades than their peers when they do – here’s that in graphical form.

Outside of the years of the examnishambles proportions remain pretty stable, even though numbers have increased in all cases. Roughly a third of POLAR quintile 5 (most advantaged) accepted applicants get AAA or above, roughly three in ten of POLAR quintile 1 (least advantaged) accepted applicants get CCC or below.

We run into another wrinkle in the UCAS data here: we don’t get tariff group acceptances by POLAR, though we do get it by IMD (and we don’t get A level points by IMD, but we do by POLAR). I’m pretty sure UCAS invented the multiple equality measure (MEMS) for precisely that reason, but we don’t appear to get that at all these days.

So here is a plot of acceptance applicants by IMD quintile (note that you can only really look at one home nation at a time due to differences in methodologies). And what is apparent is the familiar slow steady growth in less advantaged 18 year accepted applicants attributed to widening access initiatives.

Unfortunately this is a case of what we don’t see. There’s a potential happy ending where we learn that high tariff providers are massively expanding their recruitment of applicants from disadvantaged backgrounds, and that this explains both the rise in numbers and any decline in average offermaking. The growth in high tariff recruitment from low advantage quintiles is welcome, but not anything like huge enough to explain the growth in numbers.

We are left to conclude that the expansion is in all groups equally – and given that most of the best A level scores tend to go to the top of the league tables anyway, it is hard to dismiss the idea that tariffs are falling. Perhaps January’s provider level release will offer us more oblique ways to examine what should be a very straightforward question – and one (that given the influx of less academically experienced students into providers that have not historically supported students like that) may well attract regulatory interest.

We randomly got a really lovely dataset showing entry rates by Westminster constituency – and I could hardly resist plotting it alongside the 2024 election results. There is a mild correspondence between a lower entry rate and a higher Reform UK vote.

This blog was kindly authored by Professor Abigail Marks, Associate Dean of Research, Newcastle University Business School, and member of the Chartered Association of Business Schools Policy Committee.

From January 2026, public funding for the vast majority of Level 7 apprenticeships in England will be withdrawn for learners aged 22 and over. Funding will remain for those aged 16 to 21, alongside narrow exceptions for care leavers and learners with Education, Health and Care Plans. Current apprentices will continue to be supported. Ministers present the change as a rebalancing of spending toward younger learners and lower levels, where they argue returns are higher and budgets are more constrained.

At first sight, this decision looks like a simple trade-off: concentrating scarce resources on school-leavers and early career entrants, while expecting employers to bear the costs of advanced, Master’s-level training. For business schools, however, particularly those that have invested in Level 7 pathways, such as the Senior Leader Apprenticeship, the implications for widening participation are likely to be profound. The Senior Leader Apprenticeship is often integrated with an MBA or Executive MBA. Alongside this, many institutions align Level 7 apprenticeships with specialist MSc degrees, often with embedded professional accreditation. In essence, Level 7 apprenticeships in business schools provide structured, work-based routes into advanced leadership and management education, usually culminating in an MBA or MSc.

Since the apprenticeship levy was introduced in 2017, Level 7 programmes have provided business schools with a powerful route to widen participation, particularly among groups that have been historically excluded from postgraduate education. According to the Department for Education’s 2023 Apprenticeship Evaluation, almost half (48 per cent) of Level 7 apprentices are first-generation students, with neither parent having attended university, and around one in five live in the most deprived areas of the country. Analysis by the Chartered Association of Business Schools shows that in 2022/23, a quarter of business and management Level 7 apprentices held no prior degree qualification before starting, with a small minority having no formal qualifications at all. The age profile further underscores the differences between these learners and conventional Master’s students, with 88 per cent of business and management Level 7 apprentices aged over 31, indicating that these programmes primarily serve mature learners and career changers rather than recent graduates.

This picture contrasts sharply with the traditional MBA market, both in the UK and internationally. Research on MBA demographics from the Association of MBAs in 2023 highlights that students are typically in their late twenties to early thirties, often already possessing a strong undergraduate degree and professional background, and participation is skewed toward those with access to significant financial resources. An Office for Students analysis of Higher Education Statistics Agency data shows that conventional graduate business and management entrants are disproportionately from higher socio-economic backgrounds, with lower representation from disadvantaged areas compared to undergraduate cohorts. In practice, this means that the subsidised Level 7 apprenticeship route has been one of the few mechanisms allowing those without financial capital, prior academic credentials, or family background in higher education to gain access to advanced management education in business schools.

Employer behaviour is likely to shift in predictable ways once the subsidy is removed. Some large levy-paying firms may continue to sponsor a limited number of Level 7 places, but many smaller employers, as well as organisations in the public and third sectors, will struggle to justify the full cost. Data from the Chartered Management Institute suggests that 60 per cent of Level 7 management apprentices are in public services such as the NHS, social care, and local government. Less than 10 per cent are in FTSE 350 companies. Consequently, there is a risk of further narrowing provision to those already in advantaged positions.

The progression ladder is also threatened. Level 7 apprenticeships have been a natural progression for people who began at Levels 3 to 5, building their qualifications as they moved into supervisory roles. Closing the door at this point reinforces the glass ceiling for those seeking to rise from technical or frontline work into leadership. With data from the Department for Education reported in FE Week reporting that 89 per cent of Level 7 apprentices are currently aged over 22, the vast majority of those who have benefited from these opportunities will be excluded from January 2026.

The consequences extend beyond widening participation metrics. Leadership and management skills are consistently linked to firm-level productivity and the diffusion of innovation. Studies such as the World Management Survey have shown that effective management correlates strongly with higher productivity and competitiveness. Restricting adult access to advanced apprenticeships risks slowing the spread of these practices across the economy. For business schools, it reduces their ability to act as engines of regional development and knowledge transfer. At a national level, the UK’s prospects for growth depend not only on new entrants but also on upskilling the existing workforce. Apprenticeships have been one of the few proven ways of achieving this. If opportunities narrow, it is possible that firms may struggle to adopt new technologies, deliver green transitions, or address regional productivity gaps. The effects may also be felt in export performance, scale-up survival, and international competitiveness.

The removal of public funding for adults over 21 threatens to dismantle a pathway that has enabled business schools to transform the profile of their postgraduate cohorts. Where once mature students, first-generation graduates, and learners from deprived regions could progress into Master’s-level management education, the policy shift risks returning provision in England to a preserve of the already advantaged. In contrast, our European counterparts, where degree and higher-level apprenticeships retain open access for adults, will continue to allow business schools to deliver on widening participation commitments across the life course.

Germany’s dual study system has expanded, with degree-apprenticeship style programmes now making up almost five per cent of higher education enrolments. Data from the OECD shows that the proportion of young adults aged 25–34 with a tertiary degree in Germany has risen to around 40 per cent, driven partly by these integrated vocational–academic routes. Switzerland shows even more dramatic results: between 2000 and 2021, the share of 25–34-year-olds with a tertiary qualification rose from 26 to 52 per cent. Crucially, Switzerland also leads Europe in lifelong learning, with around 67.5 per cent of adults aged 25–65 participating in continuing education and training. For Swiss business schools, this creates a mature, diverse learner base and allows firms to continually upgrade leadership and management capacity. Both countries demonstrate how keeping lifelong pathways open is central to sustaining firm-level productivity, innovation, and international competitiveness.

The decision to defund most adult participation at Level 7 thus represents more than a budgetary tweak. It narrows opportunities in advanced management education and risks reversing progress in widening participation. Unless English business schools, employers, and policymakers act swiftly to design new pathways, the effect will be a return to elite provision. More worryingly, England risks falling behind international counterparts in building the leadership capacity that underpins innovation, productivity, and growth.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

As reading scores remain a top concern for schools nationwide, many districts are experimenting with ability-based grouping in the early grades. The idea is to group students in multiple grade levels by their current reading level — not their grade level. A classroom could have seven kindergartners, 10 first graders, and three second graders grouped together for reading because they all read at the same level.

While this may work for some schools, in our district, Rockwood School District in Missouri, we’ve chosen a different path. We keep students together in their class during whole-class instruction — regardless of ability level — and provide support or enrichment by creating flexible groups based on instructional needs within their grade level.

We’re building skilled, confident readers not by separating them, but by growing them together.

Children, like adults, learn and grow in diverse groups. In a Rockwood classroom, every student contributes to the shared learning environment — and every student benefits from being part of it.

Our approach starts with whole-class instruction. All students, including English multilingual learners and those working toward grade-level benchmarks, participate in daily, grade-level phonics and comprehension lessons. We believe these shared experiences are foundational — not just for building literacy, but for fostering community and academic confidence.

After our explicit, whole-group lessons, students move into flexible, needs-based small groups informed by real-time data and observations. Some students receive reteaching, while others take on enrichment activities. During these blocks, differentiation is fluid: A student may need decoding help one day and vocabulary enrichment the next. No one is locked into a static tier. Every day is a new opportunity.

Students also engage in daily independent and partner reading. In addition, reading specialists provide targeted, research-based interventions for striving readers who need additional instruction.

We build movement into our instruction, as well — not as a brain break, but as a learning tool. We use gestures for phonemes, tapping for spelling and jumping to count syllables. These are “brain boosts,” helping young learners stay focused and engaged.

We challenge all students, regardless of skill level. During phonics and word work, advanced readers work with more complex texts and tasks. Emerging readers receive the time and scaffolded support they need — such as visual cues and pre-teaching or exposing students to a concept or skill before it’s formally taught during a whole-class lesson. That can help them fully participate in every class. A student might not yet be able to decode or encode every word, but they are exposed to the grade-level standards and are challenged to meet the high expectations we have for all students.

During shared and interactive reading lessons, all students are able to practice fluency and build their comprehension skills and vocabulary knowledge. Through these shared experiences, every child experiences success.

There’s a common misconception that mixed-ability classrooms hold back high achievers or overwhelm striving readers. But in practice, engagement depends more on how we teach rather than who is in the room. With well-paced, multimodal lessons grounded in grade-level content, every learner finds an entry point.

You’ll see joy, movement, and mutual respect in our classrooms — because when we treat students as capable, they rise. And when we give them the right tools, not labels, they use them.

While ability grouping may seem like a practical solution, research suggests it can have a lasting downside. A Northwestern University study of nearly 12,000 students found that those placed in the lowest kindergarten reading groups rarely caught up to their peers. For example, when you group a third grader with first graders, when does the older child get caught up? Even if he learns and progresses with his ability group, he’s still two grade levels behind his third-grade peers.

This study echoes what researchers refer to as the Matthew Effect in reading: The rich get richer, and the poor get poorer. Lower-track students are exposed to less complex vocabulary and fewer comprehension strategies. Once placed on that path, it’s hard to catch up. Once a student is assigned a label, it’s difficult to change it — for both the student and educators.

In Rockwood, we’re confident in what we’re doing. We have effective, evidence-based curricula for Tier I phonics and comprehension, and every student receives the same whole-class instruction as every other student in their grade. Then, students receive intervention or enrichment as needed.

At the end of the 2024–25 school year, our data affirmed what we see every day. Our kindergarteners outperformed national proficiency averages in every skill group — in some cases by more than 17 percentage points, according to our Reading Horizons data. Our first and second graders outpaced national averages across nearly every domain. We don’t claim to have solved the literacy crisis — or know that our model will work for every district, school, classroom or student — but we’re building readers before gaps emerge.

We’ve learned that when every student receives strong Tier I instruction, no one gets left behind. The key isn’t separating kids by ability. It’s designing instruction that’s universally strong and strategically supported.

We recognize that every community faces distinct challenges. If you’re a district leader weighing the trade-offs of ability grouping, consider this: When you pull students out of the room during critical learning moments, the rich vocabulary, the shared texts and the academic conversation, you are not closing the learning gap, but creating a bigger one. Those critical moments build more than skills; they build readers.

In Rockwood, our data confirms what we see every day: students growing not only in skills, but also in confidence, stamina and joy. We’re proving that inclusive, grade-level-first instruction can work — and work well — for all learners.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

You could read “abolishing the 50 per cent participation target” as a vote of no-confidence in higher education, a knee-jerk appeal to culturally conservative working-class voters. But that would be both a political/tactical mistake and a fundamental misreading of the policy landscape.

To recap: in his leader’s speech to Labour Party Conference on Tuesday, Prime Minister Keir Starmer announced that two thirds of people under 25 should participate in higher level learning, whether in the form of academic, technical, or work-based training, with at least ten per cent pursuing technical education or apprenticeships by 2040.

So let’s start by acknowledging, as DK does elsewhere on the site, that the 50 per cent participation target has a totemic status in public discourse about higher education that far outweighs its contemporary relevance. And, further, that party conference speeches are a time for broad strokes and vibes-based narrativising for the party faithful, and soundbites for the small segment of the public that is paying attention, not for detailed policy discussions.

An analysis of Starmer’s speech on Labour List suggests, for example, that the new target signals a decisive break with New Labour, something that most younger voters, including many in the post-compulsory education sector, don’t give the proverbial crap about.

What this announcement does is, finally, give the sector something positive to rally around. Universities UK advocated nearly exactly this target in its blueprint for the new government, almost exactly a year ago, suggesting that there should be a target of 70 per cent participation in tertiary education at level four and above by 2040. Setting aside the 3.333 percentage point difference, that’s a win, and a clear vote of confidence in the post-compulsory sector.

Higher education is slowly recovering from its long-standing case of main character syndrome. Anyone reading the policy runes knows that the direction of travel is towards building a mixed tertiary economy, informed if not actively driven by skills needs data. That approach tallies with broader questions about the costs and financing of dominant models of (residential, full time) higher education, the capacity of the economy to absorb successive cohorts of graduates in ways that meet their expectations, and the problematic political implications of creating a hollowed out labour market in which it it is ever-more difficult to be economically or culturally secure without a degree.

The difference between the last government and this one is that it’s trying to find a way to critique the equity and sustainability of all this without suggesting that higher education itself is somehow culturally suspect, or some kind of economic Ponzi scheme. Many in the sector have at times in recent years raged at the notion that in order to promote technical and work-based education options you have to attack “university” education. Clearly not only are both important but they are often pretty much the same exact thing.

What has been missing hitherto, though, is any kind of clear sense from government about what it thinks the solution is. There have been signals about greater coordination, clarification of the roles of different kinds of institution, and some recent signals around the desirability of “specialisation” – and there’s been some hard knocks for higher education providers on funding. None of it adds up to much, with policy detail promised in the forthcoming post-16 education and skills white paper.

But now, the essay question is clear: what will it take to deliver two-thirds higher level learning on that scale?

And to answer that question, you need to look at both supply and demand. On the supply side, there’s indications that the market alone will struggle to deliver the diversity of offer that might be required, particularly where provision is untested, expensive, and risky. Coordination and collaboration could help to address some of those issues by creating scale and pooling risk, and in some areas of the country, or industries, there may be an appetite to start to tackle those challenges spontaneously. However, to achieve a meaningful step change, policy intervention may be required to give providers confidence that developing new provision is not going to ultimately damage their own sustainability.

But it is on the demand side that the challenge really lies – and it’s worth noting that with nearly a million young people not in education, employment or training, the model in which exam results at age 16 or 18 determine your whole future is, objectively, whack. But you can offer all the tantalising innovative learning opportunities you want, if people feel they can’t afford it, or don’t have the time or energy to invest, or can’t see an outcome, or just don’t think it’ll be that interesting, or have to stop working to access it, they just won’t come. Far more thought has to be given to what might motivate young people to take up education and training opportunities, and the right kind of targeted funding put in place to make that real.

The other big existential question is scaling work-based education opportunities. Lots of young people are interested in apprenticeships, and lots of higher education providers are keen to offer them; the challenge is about employers being able to accommodate them. It might be about looking to existing practice in teacher education or health education, or about reimagining how work-based learning should be configured and funded, but it’s going to take, probably, industry-specific workforce strategies that are simultaneously very robust on the education and skills needs while being somewhat agnostic on the delivery mechanism. There may need to be a gentle loosening of the conditions on which something is designated an apprenticeship.

The point is, whatever the optics around “50 per cent participation” this moment should be an invigorating one, causing the sector’s finest minds to focus on what the answer to the question is. This is a sector that has always been in the business of changing lives. Now it’s time to show it can change how it thinks about how to do that.

Everywhere you look, someone is telling students and workers to “learn AI.”

It’s become the go-to advice for staying employable, relevant and prepared for the future. But here’s the problem: While definitions of artificial intelligence literacy are starting to emerge, we still lack a consistent, measurable framework to know whether someone is truly ready to use AI effectively and responsibly.

And that is becoming a serious issue for education and workforce systems already being reshaped by AI. Schools and colleges are redesigning their entire curriculums. Companies are rewriting job descriptions. States are launching AI-focused initiatives.

Yet we’re missing a foundational step: agreeing not only on what we mean by AI literacy, but on how we assess it in practice.

Two major recent developments underscore why this step matters, and why it is important that we find a way to take it before urging students to use AI. First, the U.S. Department of Education released its proposed priorities for advancing AI in education, guidance that will ultimately shape how federal grants will support K-12 and higher education. For the first time, we now have a proposed federal definition of AI literacy: the technical knowledge, durable skills and future-ready attitudes required to thrive in a world influenced by AI. Such literacy will enable learners to engage and create with, manage and design AI, while critically evaluating its benefits, risks and implications.

Second, we now have the White House’s American AI Action Plan, a broader national strategy aimed at strengthening the country’s leadership in artificial intelligence. Education and workforce development are central to the plan.

Related: A lot goes on in classrooms from kindergarten to high school. Keep up with our free weekly newsletter on K-12 education.

What both efforts share is a recognition that AI is not just a technological shift, it’s a human one. In many ways, the most important AI literacy skills are not about AI itself, but about the human capacities needed to use AI wisely.

Sadly, the consequences of shallow AI education are already visible in workplaces. Some 55 percent of managers believe their employees are AI-proficient, while only 43 percent of employees share that confidence, according to the 2025 ETS Human Progress Report.

One can say that the same perception gap exists between school administrators and teachers. The disconnect creates risks for organizations and reveals how assumptions about AI literacy can diverge sharply from reality.

But if we’re going to build AI literacy into every level of learning, we have to ask the harder question: How do we both determine when someone is truly AI literate and assess it in ways that are fair, useful and scalable?

AI literacy may be new, but we don’t have to start from scratch to measure it. We’ve tackled challenges like this before, moving beyond check-the-box tests in digital literacy to capture deeper, real-world skills. Building on those lessons will help define and measure this next evolution of 21st-century skills.

Right now, we often treat AI literacy as a binary: You either “have it” or you don’t. But real AI literacy and readiness is more nuanced. It includes understanding how AI works, being able to use it effectively in real-world settings and knowing when to trust it. It includes writing effective prompts, spotting bias, asking hard questions and applying judgment.

This isn’t just about teaching coding or issuing a certificate. It’s about making sure that students, educators and workers can collaborate in and navigate a world in which AI is increasingly involved in how we learn, hire, communicate and make decisions.

Without a way to measure AI literacy, we can’t identify who needs support. We can’t track progress. And we risk letting a new kind of unfairness take root, in which some communities build real capacity with AI and others are left with shallow exposure and no feedback.

Related: To employers, AI skills aren’t just for tech majors anymore

What can education leaders do right now to address this issue? I have a few ideas.

First, we need a working definition of AI literacy that goes beyond tool usage. The Department of Education’s proposed definition is a good start, combining technical fluency, applied reasoning and ethical awareness.

Second, assessments of AI literacy should be integrated into curriculum design. Schools and colleges incorporating AI into coursework need clear definitions of proficiency. TeachAI’s AI Literacy Framework for Primary and Secondary Education is a great resource.

Third, AI proficiency must be defined and measured consistently, or we risk a mismatched state of literacy. Without consistent measurements and standards, one district may see AI literacy as just using ChatGPT, while another defines it far more broadly, leaving students unevenly ready for the next generation of jobs.

To prepare for an AI-driven future, defining and measuring AI literacy must be a priority. Every student will be graduating into a world in which AI literacy is essential. Human resources leaders confirmed in the 2025 ETS Human Progress Report that the No. 1 skill employers are demanding today is AI literacy. Without measurement, we risk building the future on assumptions, not readiness.

And that’s too shaky a foundation for the stakes ahead.

Amit Sevak is CEO of ETS, the largest private educational assessment organization in the world.

Contact the opinion editor at [email protected].

This story about AI literacy was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s weekly newsletter.

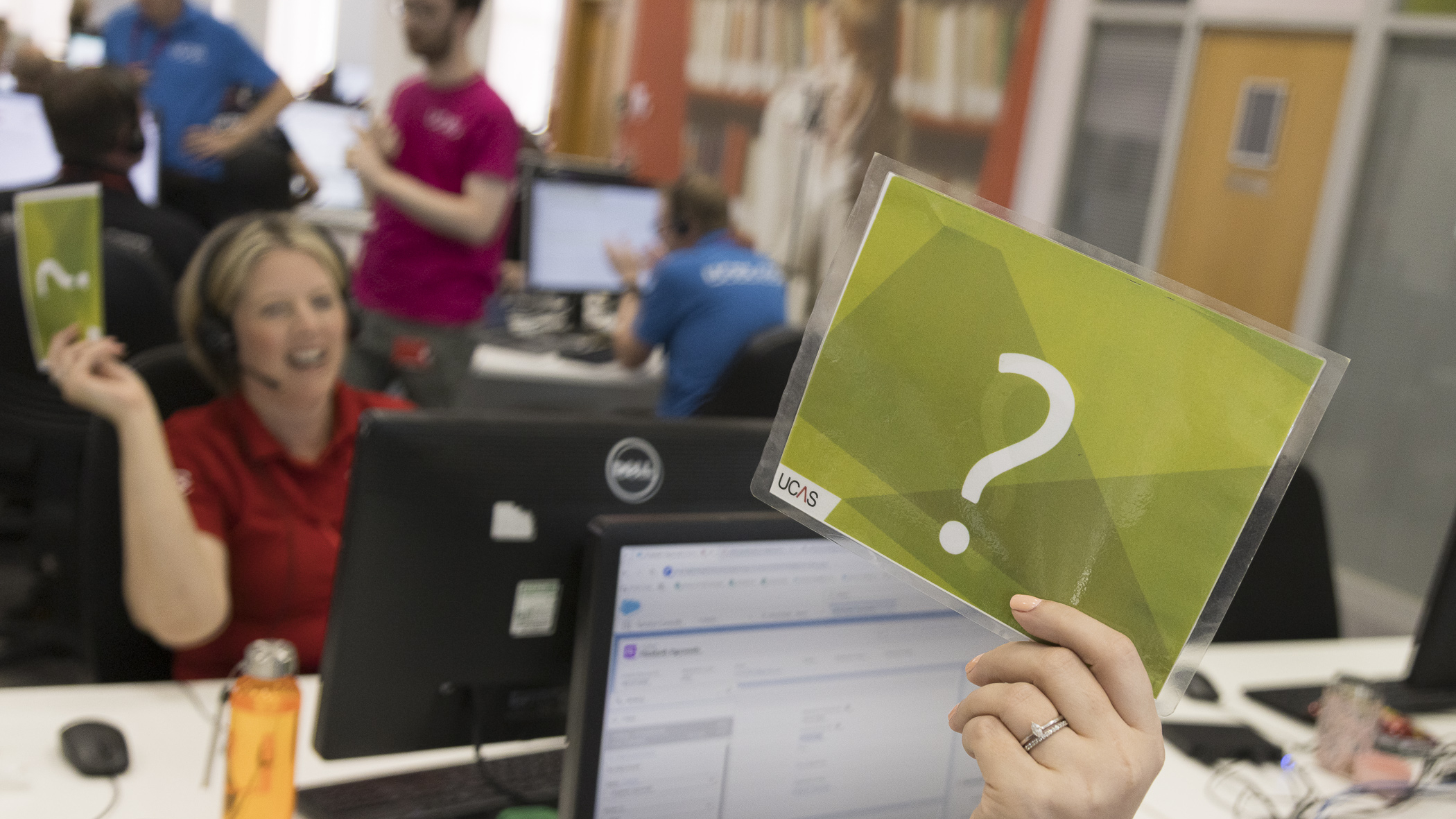

In Cheltenham they call it “UCAS Christmas” and it’s not hard to see why. Months of preparation, a whole lot of expectation riding on a single day, highs and lows of emotion, and more snacks than you can shake a stick at.

Level 3 results day at UCAS HQ has the kind of jittery manic energy that comes when a lot of people have been anticipating this day for months, and half of them have been up since 2.00am the night before. By the time I arrive, the marquee moment – the national release of admissions decisions into 700k-plus inboxes at 8.00am – has passed without a hitch and the main business of Clearing, fielding queries from anxious applicants (and their parents), is under way.

At the heart of the building sits Joint Operations Centre, or JOC for short, a room humming with the quiet buzz of people making sure the right things are happening. Courteney Sheppard, UCAS head of operations, explains that today, most UCAS people who have decision-making power on results day convene in this one space so that if anything happens that needs speedy resolution the right person is on hand. Those with deep subject expertise are housed temporarily in the office next door, ready to jump in to address issues as they arise.

All along one wall there are massive screens – at least twenty and probably more like thirty, all monitoring different data in real time. One screen simply shows the current time (because in the critical two minutes before 8.00am release there are actions that are coordinated to the second); others track web traffic, database capacity, maximum wait times for calls, social media traffic, applicant behaviours, and much more besides. Opposite the screens is a flipchart where there are already a ream of jotted notes about ways to improve for next year.

It’s easy to underestimate the logistical and technological challenge facing UCAS on results day but consider how rare it is for any system to have to cope with close to simultaneous login of every possible user. All over the country at 8.00am on the dot applicants’ UCAS results portal goes live and they can login to see whether they have secured their preferred course and higher education institution. Simultaneously they receive an email from UCAS with the same information. And, I’m told, UCAS creates a static web page for each and every applicant with the same information so that if there is any delay at all in getting into the portal, even of only a few seconds, the applicant can be redirected to the information they are looking for.

“The 8 o’clock moment is always hairy,” says Lynsey Hopkins, UCAS director of admissions. “The preparation is incredible, and takes months, because there are so many moving parts. The tech is really complex and is getting more so all the time. You always worry that if any applicant wasn’t able to see their outcomes that could ramp up their anxiety on one of the highest stakes and most stressful experiences of their young lives.”

But getting information on admissions decisions out to applicants is only the beginning. The vast majority – in fact the highest number on record this year – will have a place confirmed at their first choice of institution. Most of those will segue seamlessly into celebrating and looking forward to taking up their place. But a substantial number will pass through Clearing – and not only because they have been unlucky enough not to receive an offer from their preferred institution. Some applicants’ plans will have changed since they made their application through UCAS and will wish to decline their place in favour of a different option; others don’t even start applying until the Clearing period. Where UCAS holds data on applicants’ previous choices and qualifications the system will suggest possible matches for applicants to help them begin to sift their options.

“The largest group of people in Clearing are those who have actively put themselves there,” says Ben Jordan, UCAS head of strategy. “Clearing doesn’t have negative connotations among young people at all – it’s just a brand.”This year 92 per cent of all higher education providers are offering courses through Clearing, and there are more than 30,000 courses available, offering an enormous degree of choice to applicants.

In theory, applicants contact institutions directly, and once they have secured an offer, are able to update their applications via their UCAS portal and have the application confirmed by the institution, without active intervention from UCAS. In practice, many applicants still need help and support from the central admissions service.

Over in the “west wing” there’s the traditional call centre staffed by a mixture of UCAS’ customer service team, volunteers from across the business, and temporary staff, all sporting UCAS t-shirts, headsets and query cards they can wave to summon a senior staff member to help them answer the more complicated questions. On a normal day, UCAS has 50-60 people working on customer services; today it’s around 200.

It’s not uncommon for calls to simply consist of an applicant saying, “My UCAS portal says I got in. Did I get in?” To which the correct answer is, “Yes, you got in, hurray!” Job done to everyone’s satisfaction. But it’s much more likely that applicants have more complicated questions – predictably many lose their login information, don’t fully understand the process, and generally need a bit of hand-holding at a stressful time.

“We don’t just handle questions, we handle emotions,” says Jordan Court, customer call handler. “There can be so much riding on this day for applicants, they can get so anxious, it’s understandable they can sometimes lose the ability to deal with administrative stuff.” Every call handler, especially those volunteering receive detailed training, with a strong focus on emotional intelligence. “We tell people, ‘Imagine how you would want your child or your sibling to be treated’” says Courteney. “Nine of ten times what people want from the call is reassurance or validation, especially if they’re not able to get support from a school or college.”

While the calls come in steadily, in this day and age much of the queries are via social media or the UCAS chatbot, Cassy, which is able to resolve the more transactional questions, reducing the overall call load by around 30 per cent. Some issues require intervention: Jordan is able to resolve one query by noticing from a screenshot that an applicant is trying to access his UCAS portal via a web browser that has been designed for gamers – advising the applicant to try again with a more mainstream browser.

Without fail, everyone I speak to talks in glowing terms about their experience of being “on the phones” for Clearing. It’s clearly a formative experience for many UCAS staff, giving them a strong sense of purpose and of the importance of the work they do to connect applicants to higher education, as well as occasionally throwing up useful insight about how to improve the applicant experience.

Elsewhere in the building Jo Saxton, UCAS chief executive, is fielding media appearances and questions alongside minister for skills Jacqui Smith, who has the day before recorded a special message of congratulations to applicants from UCAS’ very own professional recording studio.

UCAS director of data and analysis Maggie Smart talks me through the extraordinary process of data analysis that underpins the talking points everyone is reading in the morning papers. As a voluntary signatory to the UK Statistics Authority’s code of practice for statistics, Maggie is responsible for making sure that anything UCAS says about what the data indicates should be verifiable with actual data published on its website.

Results day for the UCAS data team starts at 11.00pm the night before, capturing live operational data at 12.01am, wrestling it into a format that is publishable as public data, creating different datasets to inform governments in each of the UK Nations, and analysing the key insights that will inform the press release and briefing to the senior team until 5.00am. The press release covering the agreed talking points is signed off and released at 7.00am.

Following results day the team will track and publish daily Clearing data, updating the public dashboards by 11.00am each day. One innovation for this year will be publication of weekly data on use of the “decline my place” function, seeking to understand more about which applicants are more likely to take up that option.

In recent years the media around results day has presented something of a mixed picture, with celebratory stories of achievement and advice on securing a university place mixed with more critical queries of the value of higher education. For UCAS, engagement with stakeholders in government and in media is partly about giving confidence in the robustness of the system and partly about landing messages about the continued importance of higher education opportunity, in line with the emphasis on breaking down barriers to participation in UCAS’ recently published strategy.

In its next strategic period, UCAS will focus on the 250k-odd individuals who register for UCAS but never get to the point of making an application. Understanding the experiences, hopes and aspirations of that cohort will help to inform not just UCAS, but the whole HE sector on how to meet the needs of those of that cohort that could potentially benefit from higher education.

Given the complexity of the policy landscape for HE it’s invigorating to spend a day with people who share a core belief in the power of higher education to change lives, of which Ben Jordan is possibly one of the most heartfelt. As the policy narrative on access to university takes on a more regional and skills-led flavour, Ben argues that the enormous diversity of the higher education offer needs to be better understood so that students can truly appreciate the breadth of the options they have.

“I’ve seen purpose-built factories, I’ve seen racing car courses on university campuses,” he says. “These days the majority of applicants aren’t those with just A levels, it’s a much more mixed picture, and it’s so important that they understand not only what is opened up or closed off by the choices they make but how much higher education has to offer them. It’s our job to get that message out.”

This article is published in association with UCAS.

Well, it finally happened. Level 7 apprenticeship funding will disappear for all but a very limited number of younger people from January 2026.

The shift in focus from level 7 to funding more training for those aged 21 and under seems laudable – and of course we all want opportunities for young people – but will it solve or create more problems for the health and social care workforce?

The introduction of foundation apprenticeships, aimed at bringing 16- to 21-year-olds into the workforce, includes health and social care. Offering employer incentives should be a good thing, right?

Of course we need to widen opportunities for careers in health and social care, one of the guaranteed growth industries for the foreseeable future regardless of the current funding challenges. But the association of foundation apprenticeships with those not in education, employment or training (NEETs) gives the wrong impression of the importance of high-quality care for the most vulnerable sectors of our society.

Delivering personal care, being an effective advocate, or dealing with challenging behaviours in high pressured environments requires a level of skill, professionalism and confidence that should not be incentivised as simply a route out of unemployment.

Employers and education providers invest significant time and energy in crafting a workforce that can deliver values-based care, regardless of the care setting. Care is not merely a job: it’s a vocation that needs to be held in high esteem, otherwise we risk demeaning those that need our care and protection.

There are already a successful suite of apprenticeships leading to careers in health and social care, which the NHS in particular makes good use of. Social care providers (generally smaller employers) report challenges in funding or managing apprenticeships, but there are excellent examples of where this is working well.

So, do we need something at foundation level? How does that align with T level or level 2 apprenticeship experiences? If these pathways already exist and numbers are disappointing, why bring another product onto the market? And are we sending the correct message to the wider public about the value of careers in health and social care?

The removal of funding for level 7 apprenticeships serves as a threat to the existing career development framework – and it may yet backfire on foundation or level 2 apprenticeships. The opportunity to develop practitioners into enhanced or advanced roles in the NHS is not only critical to the delivery of health services in the future, but it also offers a career development and skills escalator mechanism.

By removing this natural progression, the NHS will see role stagnation – which threatens workforce retention. We know that the opportunity to develop new skills or move into advanced roles is a significant motivator for employees.

If senior practitioners are not able to move up, out or across into new roles, how will those entering at lower levels advance? Where are the career prospects that the NHS has spent years developing and honing? Although we are still awaiting the outcome of the consultation around the 10-year plan – due for publication this week with revisions to the long-term workforce plan to follow – I feel confident in predicting that we will need new roles or skill sets to successfully deliver care.

So, if no development is happening through level 7 apprenticeships, where is the money going to come from? The NHS has been suggesting that there will be alternative funding streams for some level 7 qualifications, but this is unlikely to offer employers the flexibility or choice they had through the levy.

Degree apprenticeships at level 6 have also come in for some criticism about the demographics of those securing apprenticeship opportunities and how this has impacted opportunities for younger learners – an extrapolation of the arguments that were made against level 7 courses.

Recent changes to the apprenticeship funding rules, requirements of off the job training and the anticipated changes to end-point assessment could lead to pre-registration apprenticeships in nursing and allied health being deemed no longer in line with the policy intent because of the regulatory requirements associated with them.

The workforce plan of 2023 outlined the need for significant growth of the health and social care workforce, an ambition that probably is still true although how and when this will happen may change. Research conducted by the University of Derby and University Alliance demonstrated some of the significant successes associated with apprenticeship schemes in the NHS, but also highlighted some of the challenges. Even with changes to apprenticeship policy, these challenges will not disappear.

Our research also highlighted challenges associated with the bureaucracy of apprenticeships, the need for stronger relationships between employers and providers, flexibility in how the levy is used to build capacity and how awareness of the apprenticeship “brand” needs to be promoted.

The security of our future health and social care workforce lies in careers being built from the ground up, regardless of whether career development is funded by individuals themselves or via apprenticeships. However, the transformative nature of apprenticeships, the associated social mobility, the organisational benefits and the drive to deliver high quality care in multiple settings means that we should not be quick to walk further away from the apprenticeship model.

Offering apprenticeships at higher (and all) academic levels is critical to delivering high quality care and encouraging people to remain engaged in the sector.

So, as Skills England start to roll out change, it is crucial that both the NHS and higher education remain close to policymakers, supporting and challenging decisions being made. While there are challenges, these can be overcome or worked through. The solutions arrived at may not always be easy, but they have to be evidence-based and fully focused on the need to deliver a health and social care workforce of which the UK can be proud.