Many high school seniors are now focusing on what they will do once they graduate – or how they don’t at all know what is to come.

Families trying to guide and support these students at the juncture of a major life transition likely also feel nervous about the open-ended possibilities, from starting at a standard four-year college to not attending college at all.

I am a mental health counselor and psychology professor.

Here are four tips to help make deciding what comes after high school a little easier for everyone involved:

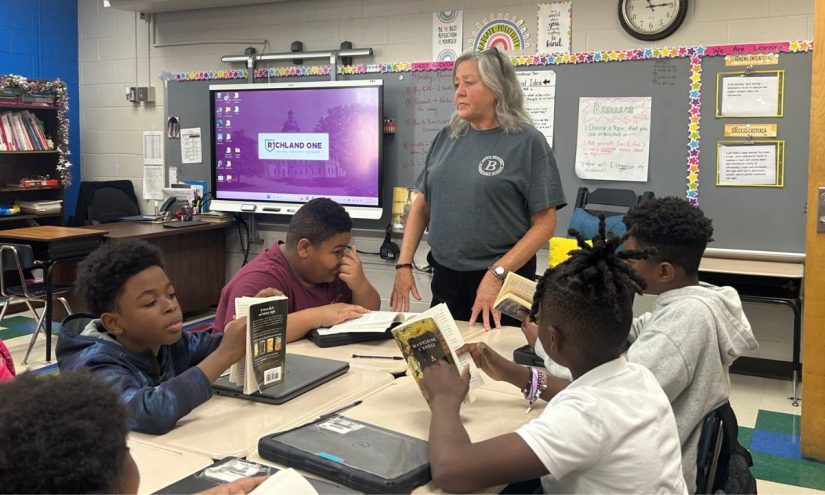

1. Shadow someone with a job you might want

I have worked with many college students who are interested in a particular career path, but are not familiar with the job’s day-to-day workings.

A parent, teacher or another adult in this student’s life could connect them with someone they shadow at work, even for a day, so the student can better understand what the job entails.

High school students may also find that interviewing someone who works in a particular field is another helpful way to narrow down career path options, or finalize their college decisions.

Research published in 2025 shows that high school students who complete an internship are better able to decide whether certain careers are a good fit for them.

2. Look at the numbers

Full-time students can pay anywhere from about US$4,000 for in-state tuition at a public state school per semester to just shy of $50,000 per semester at a private college or university. The average annual cost of tuition alone at a public college or university in 2025 is $10,340, while the average cost of a private school is $39,307.

Tuition continues to rise, though the rate of growth has slowed in the past few years.

About 56% of 2024 college graduates had taken out loans to pay for college.

Concerns about affording college often come up with clients who are deciding on whether or not to get a degree. Research has shown that financial stress and debt load are leading to an increase in students dropping out of college.

It can be helpful for some students to look at tuition costs and project what their monthly student loan payments would be like after graduation, given the expected salary range in particular careers. Financial planning could also help students consider the benefits and drawbacks of public, private, community colleges or vocational schools.

Even with planning, there is no guarantee that students will be able to get a job in their desired field, or quickly earn what they hope to make. No matter how prepared students might be, they should recognize that there are still factors outside their control.

3. Normalize other kinds of schools

I have found that some students feel they should go to a four-year college right after they graduate because it is what their families expect. Some students and parents see a four-year college as more prestigious than a two-year program, and believe it is more valuable in terms of long-term career growth.

That isn’t the right fit for everyone, though.

Enrollment at trade-focused schools increased almost 20% from the spring of 2020 through 2025, and now comprises 19.4% of public two-year college enrollment.

Going to a trade school or seeking a two-year associate’s degree can put students on a direct path to get a job in a technical area, such as becoming a registered nurse or electrician.

But there are also reasons for students to think carefully about trade schools.

In some cases, trade schools are for-profit institutions and have been subjected to federal investigation for wrongdoing. Some of these schools have been fined and forced to close.

Still, it is important for students to consider which path is personally best for them.

Research has shown that job satisfaction has a positive impact on mental health, and having a longer history with a career field leads to higher levels of job satisfaction.

4. Consider a gap year before shutting down the idea

One strategy that high school graduates have used in recent years is taking a year off between high school and college in order to better determine what is the right fit for a student. Approximately 2% to 3% of high school graduates take a gap year – typically before going on to enroll in college.

Some young people may travel during a gap year, volunteer, or get a job in their hometown.

Whatever the reason students take gap years, I have seen that the time off can be beneficial in certain situations. Taking a year off before starting college has also been shown to lead to better academic performance in college.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.