It was quite the paradox really.

Sat in a glorious space in Lisbon specifically designed for groups of students to organise events where they can eat (inexpensively) and talk together, we met a Medical student leader from Portugal and a Pharmacy student leader from Moldova who were both thinking hard about their future.

The first thing we noticed was how refreshing it was to meet student leaders from healthcare backgrounds – in systems where self-governing faculty and school communities are nurtured and valued, talented students from a broad range of disciplines go on to become policy actors that can change universities, communities, countries and even continents.

Freedom of movement had allowed Valeria to pursue both a bachelor’s and master’s in Pharmacy at the University of Lisbon – something that a funding system had helped her switch to after completing a first year in Human Resources management. But given the economic situation back home, she feels real pressure to stay.

Meanwhile Sofia – in the process of combining being a city-wide student leader with completing her fifth year in medical school – was looking at salaries for doctors across the EU and the world, and was wondering whether Portugal could ever offer the career conditions that would allow her to practice comfortably.

![]()

In the demographic midwinter

Portugal has a particularly acute version of a problem impacting countries across Europe, including the UK – a so-called demographic winter that combines a growing proportion of pension-age people that need to be supported by the tax revenues of a shrinking number of working-age people.

Around 30 per cent of young Portuguese people now live and work abroad, representing the highest emigration rate in Europe – and Portugal’s TFR (total fertility rate), the average number of children born per woman, has remained stubbornly below the replacement level of 2.1 since the 1980s.

It all creates a hugely difficult feedback loop – fewer young workers means declining tax revenues, which constrains public investment in services that might otherwise entice them to stay, which then prompts more to leave.

That means that governments need immigration – but despite political pleas to value diversity as an extension of the European ideal, the pace and volume of that immigration, coupled with the ageing of the electorate, then emboldens far-right parties like Portugal’s Chenga! (“Enough!”) – which has gone from securing just 1.3 per cent of the vote and a single seat in the Assembly of the Republic in 2019 to just under 20 per cent of the vote and 50 seats last year.

Despite Brexit ending formal freedom of movement with the EU, we are of course experiencing our own internal migration patterns that mirror these issues. Graduates from economically disadvantaged regions consistently flow toward London and other major economic hubs, rarely returning to their hometowns. Our internal “brain drain” exacerbates demographic decline in already struggling regions, with rural areas, post-industrial towns, and coastal communities particularly affected.

The prospect of university campus closures in our demographically challenged regions threatens to accelerate this pattern – creating a parallel to Portugal’s feedback loop but on a national scale. Without coordinated government planning to create and retain talent in these areas through strategic investment, improved infrastructure, and meaningful employment opportunities, the UK risks a deepening divide between its prosperous urban centres and increasingly hollowed-out regions and towns.

![]()

Educating them to leave

To get birth rates up, back in January we’d heard how Hungary’s populist President was implementing a pronatalist strategy using education policy – offering student loan forgiveness for female graduates who have children after studies, with full debt cancellation for mothers of three+ children, as well as lifetime income tax exemptions for women with four+ children.

But even if you set aside the politics of programmes like that, the big question is whether they work. Having previously offered returning expatriates tax reductions of up to 70 per cent for five years – 90 per cent for those relocating to the economically disadvantaged south – in Italy Giorgia Meloni’s government has been forced into a dramatic retreat, citing the unsustainable €1.3 billion annual cost and limited evidence of efficacy.

It puts all Portugal’s higher education sector in real difficulty. Both student and university leaders know that modernised higher education and skills systems are central to any country’s economic future. But if the expenditure involved only ends up boosting the Netherlands’ or Germany’s economies, sustaining low fees and circa 50 per cent participation rates will get harder and harder.

Just over a year ago, the centre-right minority coalition led by Prime Minister Luís Montenegro of the Social Democratic Party (PSD) and the CDS People’s Party (CDS–PP) responded with a multi-year graduate tax holiday – workers aged 18-26 (up to 30 for master’s/PhD holders) qualify for income tax exemptions over five years, and additional benefits exist for graduates moving to rural areas through the “Incentivo à Fixação de Jovens no Interior” program, including extra tax deductions and housing support.

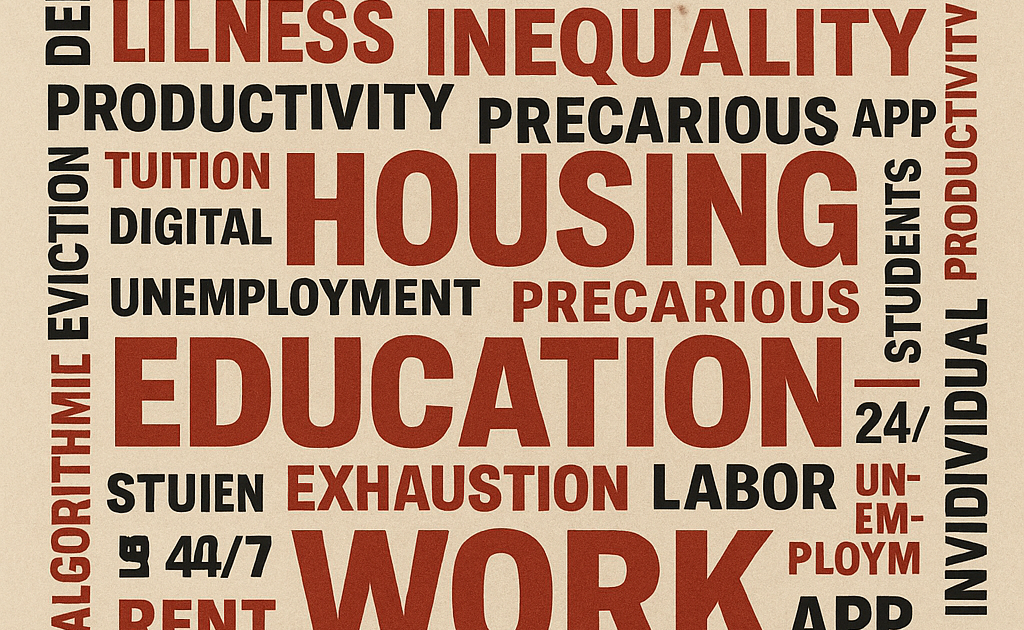

But the benefits are pretty small when weighed against the rising cost of living, especially in major cities – base salaries remain uncompetitive, and they don’t fix the country’s acute housing problem, which sees students, graduates and migrants fighting for substandard housing in a country whose tourism-dependant economy has tended to turn much of its cities’ property portfolio into holiday lets.

And following the collapse of the coalition earlier this year, a fresh general election is to be staged – and pretty much all of the country’s student groups have the cost and availability of housing as a top priority.

![]()

What goes on tour

It was one of the many issues we ended up discussing on our two-day study tour to Portugal, where 30 UK student leaders (and the staff that support them) traversed Lisbon, Coimbra, Barcelos and Porto to build connections, share ideas and identify solutions to the problems besetting both students and the higher education systems in which they are partners.

So many of the issues faced by students sounded familiar – the obvious difference each time being that at least the Portuguese government is trying.

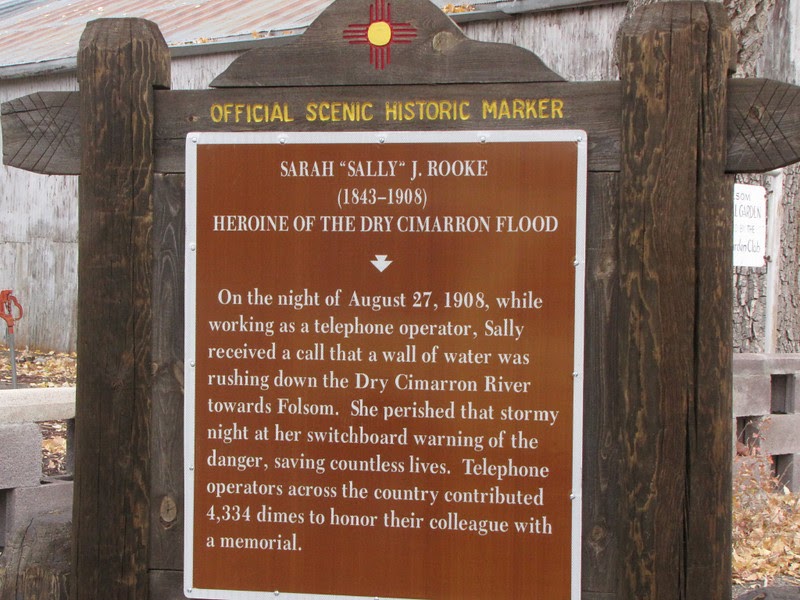

Its National Higher Education Accommodation Plan (PNAES) launched in 2022, and aims to deliver over 18,000 new student beds by 2026 with a €486 million investment. Then in September 2024, Prime Minister Luís Montenegro’s “Student Accommodation Now” emergency programme added 709 beds, and a €5.5 million credit line was established for universities to secure additional housing – all because the failure to provide housing “frustrates people’s efforts” and “stifles their ability to develop their talent”. The Prime Minister put it like this:

It is repugnant, from a civic point of view, that a student can battle for twelve years to enter higher education, only to find they cannot attend because they have nowhere to stay near the institution that accepted them.

In one of the groups I was in, one of the student leaders asked us what our own politicians had said about student housing and its role in educational opportunity, and what was in our countries’ student housing strategies. Our delegates’ faces turning blank, I had to admit that the the closest we’d got to a plan back home was former minister Robert Halfon repeatedly saying that it wasn’t his problem and was actually students’ fault:

…the government has no role in the provision of student accommodation…applicants who require student accommodation should take its availability into account when making decisions about where to study.

Housing isn’t the only thing they’ve been working on in Portugal. In 2022, the government set up an independent commission to evaluate the implementation of its Legal Framework for Higher Education Institutions (RJIES) – their equivalent to England’s Higher Education and Research Act.

Led by an 8-person panel that included two student reps, the commission’s recommendations included the creation of a single, consolidated legal instrument – a Statute for higher education students – that would define their rights and duties clearly and comprehensively, standardise protections across all institutions, and recognise the diversity of student profiles (including student workers, student parents, and students in volunteer roles).

Mental health was also prioritised – the Commission recommended strengthening support through dedicated student mental health services integrated into broader academic and social support strategies, and the revised RJIES now explicitly includes a duty for higher education institutions to contribute to student wellbeing, and specifically mentions their responsibility to guarantee mental health services. Universities will be also expected to hit psychologists:students ratios.

The Commission found that while student participation is formally recognised, in practice it can be marginal or symbolic – and recommended ensuring real, effective participation of students in institutional governance (General Councils, Academic Senates, Scientific and Pedagogical Councils), strategic planning processes, and evaluation and quality assurance activities.

The resulting arrangements will strengthen student voting power significantly – in the overhauled election process for rectors and presidents, students will hold at least 20 per cent of the weighted voting power.

And the new law explicitly details the competencies and election process for student ombudspeople – Portugal introduced university-level complaints adjudication in 2007 to tip the balance towards students, and will now mandate consistency in the role and broader student participation in their election.

Given the distance (both in time and governance) of the OIA from students and their problems, and the sorry state of independent adjudication in Scotland and NI, we really do now feel miles behind as a country on student rights protection.

![]()

Binary, but not a divide

After a visit to the (very) student city of Coimbra, the bus rolled into the Barcelos campus of the Polytechnic of Cávado and Ave – Portugal’s newest public higher education institution. IPCA had been formed as part of a national strategy to expand and decentralise higher education in Portugal – with regional provision aimed at driving regional development and addressing the need for skilled professionals in emerging industries.

The student leaders we met both from IPCA’s SU and FNAEESP (the National Federation of Polytechnic Higher Education Student Associations) were exercised about RJIES reform – partly because the status of polytechnics had become a key issue in the debate.

We tend to bristle at mentions of a binary divide, but Portugal maintains one – and FNAEESP reps were clear in their position, firmly favouring preservation with what they called “sharper clarification” to ensure polytechnics maintained their focus on vocational, technical education and practice-oriented research.

They also pushed for a “symmetrical structure” where both types of institutions would face equivalent requirements without compromising their distinct missions:

The polytechnic sector isn’t asking to become something it’s not… we’re asking for recognition of what we already are – institutions providing high-quality technical and professional education that drives regional development.

When we explained that our abolition of the binary had happened over thirty years ago, one of the reps perceptively asked us if that had raised the profile of the provision, or just hidden it. When we then explained the way in which large parts of the UK’s politics seem to ignore the technical and professional provision on offer in the sector – centring their critiques about “too many students at university” in assumptions about what a “university” is – we got a wry smile.

The upshots in Portugal are that the binary divide will be maintained but made more flexible, allowing polytechnics that offer doctoral programs to adopt the title “Polytechnic University” while preserving their focus on advanced technical education and applied research for regional development.

That will come with stricter requirements – including improved staff-to-student ratios (one PhD holder per 20 students instead of 30) and a broader range of degree offerings that maintain an applied, professional focus – and the updated RJIES framework will preserve the distinctive applied mission, partly to maintain public understanding and support for the investment that part of the system needs.

![]()

The price of chips

Even in huge universities like the University of Lisbon, the previous evening we’d seen a similar commitment to the prominent status of technical education. Opposite Team Wonkhe’s hotel was Técnico, which we’d only realised was the university’s Science and Technology faculty when leafing through a strategy brochure. The brand police would never let that happen in the UK.

Its stunning Alameda campus is located at the top of the hill overlooking Fonte Luminosa, and was designed just as António de Oliveira Salazar’s Estado Novo regime was keen to build symbols of national pride and progress.

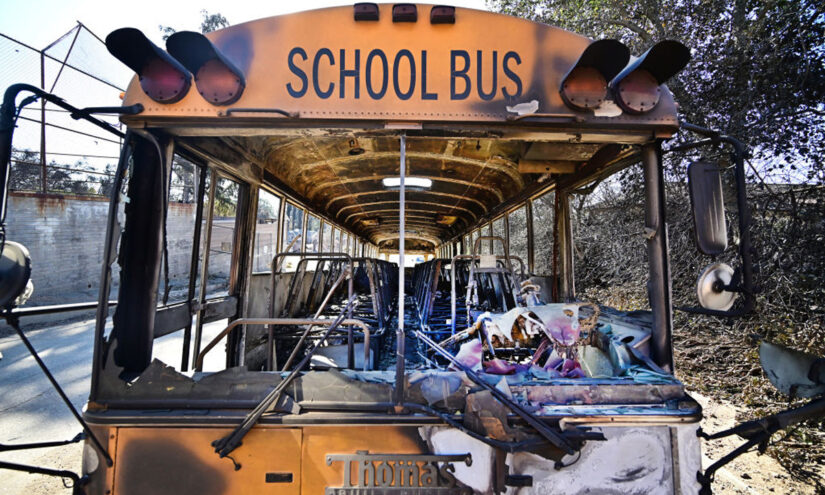

But during the dictatorship, the SU building had become a central hub for meetings, discussions, and coordination of resistance to the authoritarian government – which forced anyone who wanted to work in academia to be vetted by the political police, who had the right to arrest anyone deemed to be against the regime.

For a long time higher education had not been an instrument for growth or for people to improve their lives and prospects, but was about maintaining the hegemony of the ruling upper class. Even when Estado Novo eventually opened up universities to a broader range of the population, centres of research were created outside the universities so that young people would not get any new ideas.

Fernando Rosas, one of the founders of the socialist party Bloco de Esquerda, recalls 4 December 1968, when students broke into a building and had a “political picnic” to protest against the terrible food in the cafeteria:

That day, I woke up politically. Until then I had not been interested in such matters. But I heard the speeches about nutrition and the colonial wars, became an activist and later one of the leaders of the student union… what we in the student union did was part of the foundation of the military movement that then led to the revolution. We trained them to be engineers but also taught them to fight for freedom.

Photos up around the building tell the tales of struggles to end daily oppression, ensure universal access to education, healthcare, and political rights, and build a fraternal, inclusive and participatory society. After the Carnation Revolution at Tecnico, students’ votes carried equal weight to teachers, with student groups collectively voting on grades despite teacher assessments being reduced to suggestions:

We gained freedom to design our own curricula and research without fear of imprisonment or censorship.

Today the demonstrations might be gone, and on Thursday’s evidence we can’t say that the food has got much better – but the spirit of democracy lives on. Reforms to the curriculum at Tecnico introduced amidst austerity (which we look at elsewhere on the site here) focus on interdisciplinarity and student choice, with student associative activity – sharing power with eachother and with the university – embedded carefully into every level of the student experience, from programme to faculty to university to city to country to continent.

At the central university level, three of Lisbon’s values are familiar – intellectual freedom and respect for ethics, societal innovation and development, and social and environmental responsibility – but when we spoke with vice-rector João Peixoto, a less familiar fourth emerged as something just as important:

Students are part of the power system – they have a say, they have votes, and we cannot ignore them…democratic participation is not just something we say; it’s something we do, every day, in every council, with every voice heard.

Students across the university have voting rights, sit on councils, shape curricula, and deliver through students’ associations a large part of what we’d give a professional services department to “provide” – not as guests or consumers, but as citizens of the university community:

Our history reminds us: students fought for democracy in Portugal, and today, they still have a seat in deciding its future.

The way that culture had paid forward into the future culture of the country was vivid in Portugal’s history. That culture’s relative weakness, dismissal and continued erosion in the UK’s system should cause us to worry a lot about our future.

![]()