Elsewhere on the site, Esther Stimpson, Dave Phoenix and Tony Moss explain an obvious injustice.

Universal Credit (UC) reduces by 55p for every £1 earned as income – unless you’re one of the few students entitled to UC, where instead it is reduced by £1 for every £1 you are loaned for maintenance.

To be fair, when Universal Credit was introduced, the income disregards in the old systems that recognised that students spend out on books, equipment and travel were rolled into a single figure of £110 a month.

Taper rates were introduced to prevent “benefit traps” where increasing earnings led to disproportionately high reductions in support – and have gone from 65p initially, then to 67p, and now to 55p.

But for students, there’s never been a taper rate – and that £110 for the costs of books, equipment and travel hasn’t been uprated in over 13 years. Lifelong learning my eye.

The olden days

The student finance system in England is full of these problems – probably the most vexing of which is the parental earnings threshold over which the system expects parents to top up to the maximum.

It’s been set at £25,000 since 2008 – despite significant growth in nominal earnings across the economy since then. IFS says that if the threshold had been uprated since 2008, it would now be around £36,500 (46 per cent higher) in 2023/24.

That explains how John Denham came to estimate that a third of English domiciled students would get the maximum maintenance package back in 2007. We’re now down to about 1 in 5.

Add in the fact that the maximums available have failed to increase by inflation – especially during the post-pandemic cost of living spikes – and there’s now a huge problem.

It’s a particular issue for what politics used to call a “squeezed middle” – the parents of students whose families would have been earning £25,000 in 2007 now have £4,000 more a year to find in today’s money.

And thanks to the increases in the minimum wage, the problem is set to grow again – when the Student Loans Company comes to assess the income of a single parent family in full time (40 hours) work, given that’s over the £25,000 threshold, it will soon calculate that even that family has to make a parental contribution to the loan too.

It’s not even as if the means test actually works, either.

Principles

How much should students get? Over twenty years ago now, the higher education minister charged by Tony Blair with getting “top-up fees” through Parliament established two policy principles on maintenance.

The first was Charles Clarke’s aspiration to move to a position where the maintenance loan was no-longer means tested, and made available in full to all full-time undergraduates – so that students would be treated as financially independent from the age of 18.

That was never achieved – unless you count its revival and subsequent implementation in the Diamond review in Wales some twelve years later.

Having just received results from the Student Income and Expenditure Survey (SIES) the previous December, Clarke’s second big announcement was that from September 2006, maintenance loans would be raised to the median level of students’ basic living costs –

The principle of the decision will ensure that students have enough money to meet their basic living costs while studying.

If we look at the last DfE-commissioned Student Income and Expenditure Survey – run in 2021 for the first time in eight years – median living and participation costs for full-time students were £15,561, so would be £18,888 today if we used CPI as a measure.

The maximum maintenance loan today is £10,227.

The third policy principle that tends to emerge from student finance reviews – in Scotland, Wales and even in the Augar review of Post-18 review of education and funding – is that the value of student financial support should be linked somehow to the minimum wage.

Augar argued that students ought to expect to combine earning with learning – suggesting that full-time students should expect to be unable to work for 37.5 hours a week during term time, and should therefore be loaned the difference (albeit with a parental contribution on a means test and assuming that PT work is possible for all students on all courses, which it plainly isn’t).

As of September, the National Living Wage at 37.5 hours a week x 30 weeks will be £13,376 – some £2,832 more than most students will be able to borrow, and more even than students in London will be able to borrow.

And because the Treasury centrally manages the outlay and subsidies for student loans in the devolved nations for overall “equivalence” on costs, both Scotland and Wales have now had to abandon their minimum wage anchors too.

Diversity

Augar thought that someone ought to look at London weighting – having not managed to do so in the several years that his project ran for, the review called London a “subject worthy of further enquiry”.

Given that the last government failed to even respond to his chapter on maintenance, it means that no such further work has been carried out – leaving the uprating of the basic for London (+25 per cent) and the downrating for those living at home (-20 per cent) at the same level as they were in the Education (Student Loans) Regulations 1997.

Augar also thought student parents worthy of further work – presumably not the subject of actual work because it was DfE officials, not those from the DWP, who supported his review. Why on earth, wonder policymakers, are people putting off having kids, causing a coming crisis in the working age/pensionable age ratio? It’s a mystery.

Commuters, too. The review supported the principle that the away/home differential should be based on the different cost of living for those living at home but it “suggested a detailed study of the characteristics and in-study experience of commuter students and how to support them better.” It’s never been done. Our series would be a good place to start.

Things are worse for postgraduates, of course. Not only does a loan originally designed to cover both now go nowhere near the cost of tuition and maintenance, the annually updated memo from the DWP (buried somewhere in the secondary legislation) on how PG loans should be treated viz a vis the benefits system still pretends that thirty per cent of the loan should be treated as maintenance “income” for the purposes of calculating benefits, and the rest considered tuition spend.

(Just to put that into context – thirty per cent of the current master’s loan of £12,471 is £3,741. 90 credits is supposed to represent 1800 notional hours that a student is spending on studying rather than participating in the labour market. The maintenance component is worth £2.08 an hour – ie the loan is £16,851 short on maintenance alone for a year which by definition involves less vacation time).

Carer’s Allowance is available if you provide at least 35 hours of care a week – as long as you’re not a full-time student. Free childcare for children under fives? Only if you’re not a full-time student. Pretty much all of the support available from both central government and local authorities during Covid? Full-time students excluded.

When ministers outside of DfE give answers on any of this, they tell MPs that “the principle” is that the benefits system does not normally support full-time students, and that instead, “they are supported by the educational maintenance system.” What DWP minister Stephen Timms really means, of course, is thank god our department doesn’t have to find money for them too – a problem that will only get worse throughout the spending review.

Whose problem?

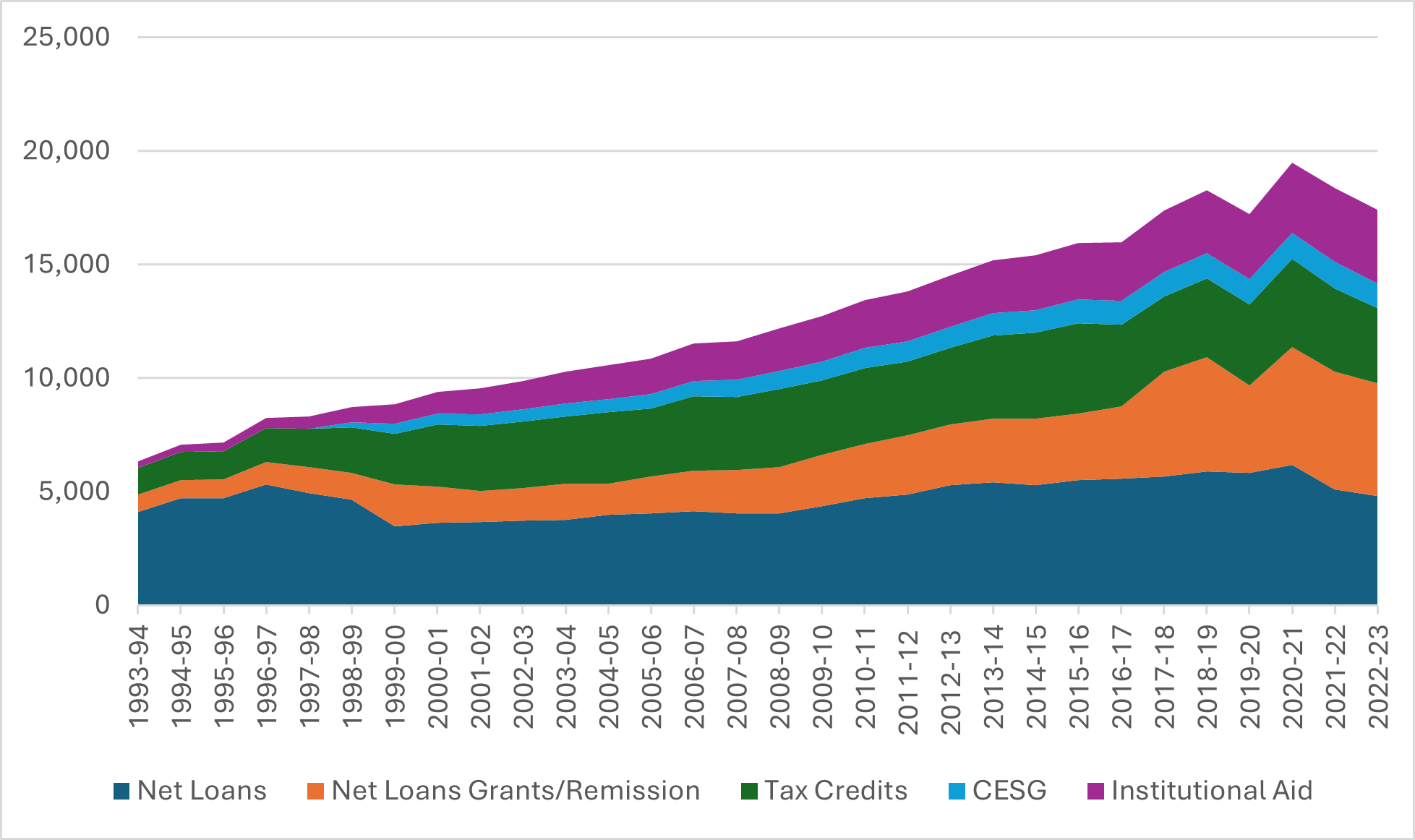

Back in 2004, something else was introduced in the package of concessions designed to get top-up fees through.

As was also the case later in 2012, the government naively thought that £3,000 fees would act as an upper limit rather than a target – so Clarke announced that he would maintain fee remission at around £1,200, raise the new “Higher Education grant” for those from poorer backgrounds to £1,500 a year, and would require universities to offer bursaries to students from the poorest backgrounds to make up the difference.

It was the thin end of a wedge. By the end of the decade, the nudging and cajoling of universities to take some of their additional “tuition” fee income and give it back to students by way of fee waivers, bursaries or scholarships had resulted in almost £200m million being spent on financial support students from lower income and other underrepresented groups – with more than 70 per cent of that figure spent on those with a household income of less than £17,910. By 2020-21 – the last time OfS bothered publishing the spend – that had doubled to £406m.

It may not last. The principle is pretty much gone and the funding is in freefall. When I looked at this last year (via an FOI request), cash help per student had almost halved in five years – and in emerging Access and Participation Plans, providers were cutting financial support in the name of “better targeting”.

You can’t blame them. Budgets are tight, the idea of redistributing “additional” fee income a lost concept, and the “student premium” funding given to universities to underpin that sort of support has been tumbling in value for years – from, for example, £174 per disabled student in 2018/19 to just £129 now.

All while the responsibility for the costs to enable disabled students to access their education glide more and more onto university budgets – first via a big cut in the last decade, and now via slices of salami that see pressure piled on to staff who get the blame, but don’t have the funding to claim any credit.

Pound in the pocket

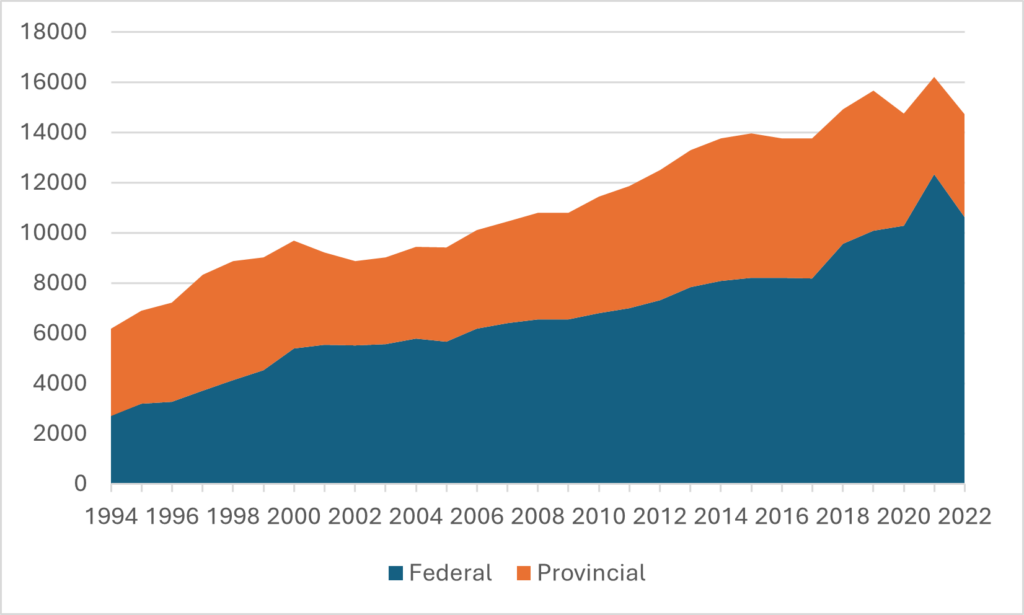

What about comparisons? By European standards, our core system of maintenance looks fairly generous – in this comparison of monthly student incomes via Eurostudent, for example, we’re not far off top out of 20 countries:

![]()

But those figures in Euros are deceptive. Our students – both UG and PG – spend fewer years as full time students than in almost every other country. Students’ costs are distorted by a high proportion studying away from home – something that subject and campus rationalisation will exacerbate rather than relieve.

And anyway, look at what happens to the chart when we adjust for purchasing power:

![]()

How are students doing financially three years on? The Student Income and Expenditure Survey (SIES) has not been recommissioned, so even if we wanted to, we’d have no data to supply to the above exercise. The Labour Force Survey fails to capture students in (any) halls, and collects some data through parents. Households Below Average Income – the key dataset on poverty – counts tuition fee loans as income, despite my annual email to officials pointing out the preposterousness of that. How are students doing financially? We don’t really know.

And on costs, the problems persist too. There’s no reliable data on the cost of student accommodation – although what there is always suggests that it is rising faster than headline rates of inflation. The basket of goods in CPI and RPI can’t be the same as for a typical student – but aside from individual institutional studies, the work has never been done.

Even on things like the evaluation of the bus fare cap, published recently by the Department for Transport, students weren’t set up as a flag by the department – so are unlikely to be a focus of what’s left from that pot after the spending review. See also health, housing, work – students are always DfE’s problem.

Student discounts are all but dead – too many people see students as people to profit from, rather than subsidise. No government department is willing to look at housing – passed between MHCLG and DfE like a hot potato while those they’d love to devolve to “other” students as economic units or nuisances, but never citizens.

The business department is barely aware that students work part-time, and the Home Office seems to think that international students will be able to live on the figure that nobody thinks home students can live on. DfE must have done work, you suppose they suppose.

In health, we pretend that student nurses and midwives are “supernumerary” to get them to pay us (!) to prop up our creaking NHS. And that split between departments, where DfE loans money to students for four years max, still means that we expect medical students in their final two years – the most demanding in terms of academic content and travelling full time to placements – to live on £7,500 a year. Thank god, in a way, that so few poor kids get in.

It’s not even like we warn them. UK higher education is a £43.9 billion sector educating almost 3m students a year, professes to be interested in access and participation, and says it offers a “world-class student” experience. And yet it can’t even get its act together to work out and tell applicants how much it costs to participate in it – even in one of the most expensive cities in the world.

Because reasons

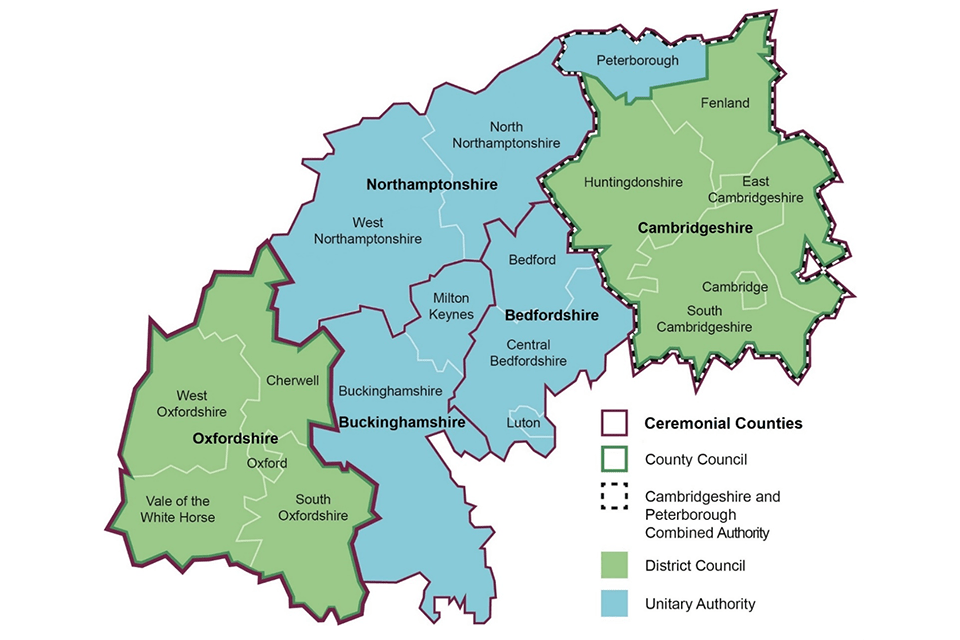

Why are we like this? It’s partly about statecraft. There was an obvious split between education and other departments when students were all young, middle class and carefree, and devolution gave the split a sharper edge – education funding (devolved) and benefits (reserved).

It’s partly about participation. It’s very tempting for all involved to only judge student financial support on whether it appears to be causing (or at least correlates with) overall enrolment, participation and completion – missing all of the impacts on the quality of that participation in the process.

Do we know what the long-term impacts are on our human capital of “full-time” students being increasingly anxious, lonely, hungry, burdened and, well, part-time? We don’t.

Efficiency in provider budgets is about getting more students to share cheaper things – management, space, operating costs and even academics. Efficiency for students doesn’t work like that – it just means spending less and less time on being a student.

The participation issue is also about the principal – we’ve now spent decades paying for participation expansion ambitions by pushing more and more of the long-run run cost onto graduates – so much so that there’s now little subsidy in the system left.

And now that the cost of borrowing the money to lend to students is through the roof, increases in the outlay look increasingly impossible.

Lifelong moaning

But something will have to give soon. Some five years after Boris Johnson gave a speech at Exeter College announcing his new Lifetime Skills Guarantee, there’s still no news on maintenance – only ever a vague “maintenance loan to cover living costs for courses with in-person attendance” to accompany the detailed tables of credits that get chunked down from the FT £9,535.

The LLE was partly a product of Augar (more on that on Wonk Corner) – who said that maintenance support should be reserved for those studying at a minimum level of intensity – 25 per cent (15 ECTS a year), and then scaled by credit.

But think about that for a moment, setting aside that increasingly arbitrary distance learning differential. Why would a student studying for 45 credits only get 3/4 of an already inadequate loan? Will students studying on one of those accelerated degrees get 1.5 x the loan?

The centrality of credit to the LLE – and its potential use in determining the level of student financial support for their living and participation costs – is fascinating partly because of the way in which a row between the UK and other member states played out back in 2008.

When ECTS was being developed, we (ie the UK) argued that the concept focused too heavily on workload as the primary factor for assigning credits. We said that credits should be awarded based on the actual achievement of learning outcomes, rather than simply the estimated workload.

That was partly because the UK’s estimate at the time of 1,200 notional learning hours (derived from an estimate of 40 hours’ notional learner effort a week, multiplied by 30 weeks) was the lowest in Europe, and much lower than the 1,500-1,800 hours that everyone else in Europe was estimating.

Annex D of 2006’s Proposals for national arrangements for the use of academic credit in higher education in England: The Final report of the Burgess Group put that down to the UK having shorter teaching terms and not clocking what students do in their breaks:

It could be argued that considerably more learner effort takes place during the extended vacations and that this is not taken into account in the total NLH for an academic year.

Those were the days.

In the end an EU fudge was found allowing the UK to retain its 20 notional hours – with a stress that “how this is applied to a range of learning experiences at a modular or course level will differ according to types of delivery, subject content and student cohorts” and the inclusion of “time spent in class, directed learning, independent study and assessment.”

A bit like with fees and efficiency, if in the mid noughties it was more likely that students were loaned enough to live on, were posh, had plenty of spare time and had carefree summers, that inherent flex meant that a student whose credit was more demanding than the notional hours could eat into their free time to achieve the learning outcomes.

But once you’ve got a much more diverse cohort of students who are much more likely to need to be earning while learning, you can’t really afford to be as flexible – partly because if you end up with a student whose characteristics and workload demand, say, 50 hours a week, and a funding system that demands 35 hours’ work a week, once you sleep for 8 hours a night you’re left with less than 4 hours a day to do literally anything else at all.

Think of it this way. If it turns out that in order to access the full maintenance loan, you have to enrol onto 60 ECTS a year (the current “full-time” position), we are saying to students that you must enrol onto credits theoretically totalling at the very very least 1,200 hours of work a year. We then loan them – as a maximum – £8.52 an hour (outside London, away from home). No wonder they’re using AI – they need to eat.

If it then turns out that you end up needing to repeat a module or even a year, the LLE will be saying “we’ve based the whole thing on dodgy averages from two decades ago – and if you need to take longer or need more goes at it, you’ll end up in more debt, and lose some of your 4 years’ entitlement in the process”. Charming.

A credit system whose design estimated notional learning hours around students two decades ago, assumed that students have the luxury of doing lots of stuff over the summer, and fessed up that it’s an unreliable way of measuring workload is not in any world a sensible way to work out how much maintenance and participation cost support to loan to a student.

Pretty much every other European country – if they operate loans, grants or other entitlements for students – regards anyone studying more than 60 (or in some cases, 75) credits as studying “full-time”.

That allows students to experience setbacks, to accumulate credit for longer, to take time out for a bereavement or a project or a volunteering opportunity – all without the hard cliff edges of “dropping out”, switching to “part-time” or “coming back in September”. Will our student finance system ever get there? Don’t bet on it.

If the work (on workload) isn’t done, we’ll be left with definitions of “full-time” and “part-time” student that are decades old – such that a full-time student at the OU can’t get a maintenance loan, while an FT UG at a brick university that barely attends in-person can – that pretty much requires students to study for more credit than they can afford to succeed in.

Oh – and if the loan is chunked down for a 30 credit module, how will the government prevent fraud?

Via an FOI request, the SLC tells me that last year, almost 13,000 students FT students in England and Wales managed to pull down installment 1 of their loan without their provider pulling down installment 1 of the fee loan. Anyone that thinks that’s all employer funding will shortly be getting my brochure on bridges.

Maintenance of a problem

Our system for student living and participation costs may, by comparison with other systems, appear to be a generous one – especially if you ignore the low number of years that students are in it, and how much they eventually pay back. But make no mistake – our student finance system is completely broken – set up for a different sector with different students that has no contemporary basis in need, ambition or impact.

Its complexity could not be less helpful for driving opportunity, its paucity is likely to be choking our stock of human (and social) capital (and resultant economic growth), and its immediate impacts have normalised food banks on campus – real poverty that universities neither can nor should be expected to alleviate with other students’ fees and debt.

The signals and signs are of danger ahead – a minister keen to stress that the “fundamentals” of the system we have for funding higher education won’t change reminds us both of a lack of money and a bandwidth issue. It’s one whose solution requires real research, cross-departmental and nations working, and a proper sense of what we want students to be, experience and learn. Sadly, that also sounds like a solution that lends itself to long grass.

Given everything else going on in the world right now, maybe that’s inevitable. But decade after decade, every time we put off a proper review, or over-prioritise university rather than student funding in the debates, we dodge the difficult questions – because they’re too complex, because the data isn’t there, because it’s another department’s problem, because reasons.

If Bridget Phillipson is serious about “fixing the foundations” to “secure the future of higher education” so that “students can benefit from a world-class education for generations to come”, she needs to commission a dedicated student maintenance review. Now.