The sector regularly discusses first-year pedagogy as a way of supporting the whole student body, but direct entrants who transition into later years are largely overlooked in policy and practice.

The recent post-16 education and skills white paper brings attention to the need for more flexible learning and progression routes to create a more integrated tertiary system, where students between different levels of study can progress more easily without rigid barriers.

As someone who joined university directly into the second year, I felt a mix of imposter syndrome and disorientation. I remember the quiet confusion of arriving on a campus that seemed to have already moved on without me. My peers already seemed to have established their routines, connected with peers, and form a sense of identity within the institution.

While the institution welcomed me, its systems did not seem to notice I had arrived. That experience stayed with me, revealing how much of university life, from induction to academic support, is designed for students who all start together in first year, leaving little space for those who join later.

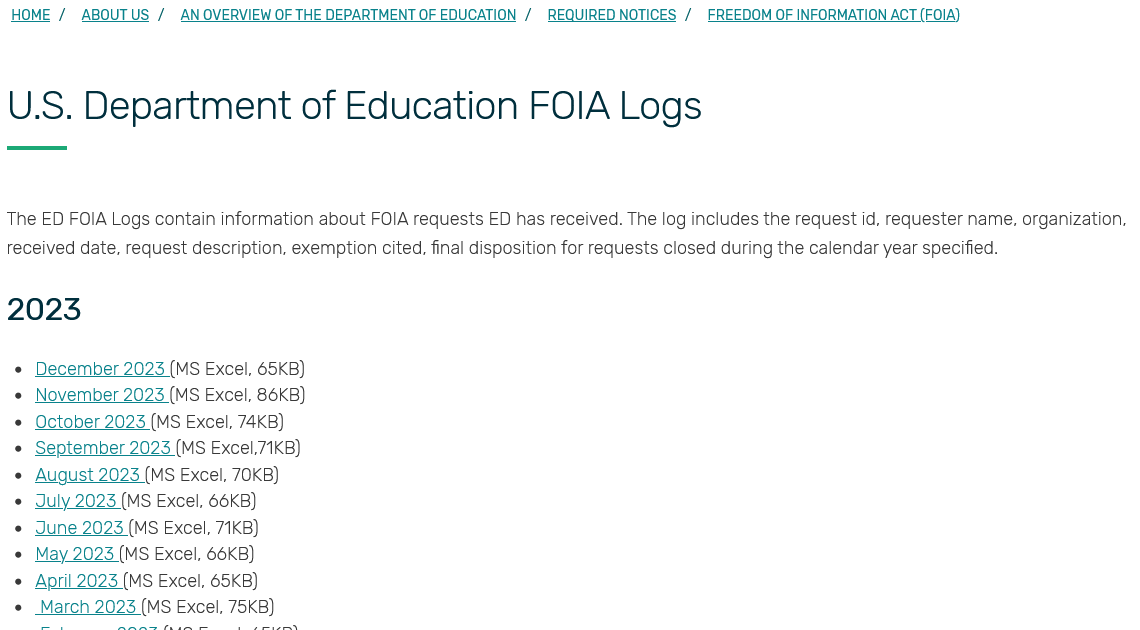

Higher education has mapped the journey and experience of many student groups. When it comes to direct entrant students, they remain absent from the map – a ghost town in literature and practice. If you happen to find research, it tends to label them as “top-up” or “advanced entry”, yet official statistics still categorise them as “continuing students”, never highlighting when they actually began their degree. This invisibility is particularly striking given the white paper’s push for diverse entry routes, modular learning, and the Lifelong Learning Entitlement.

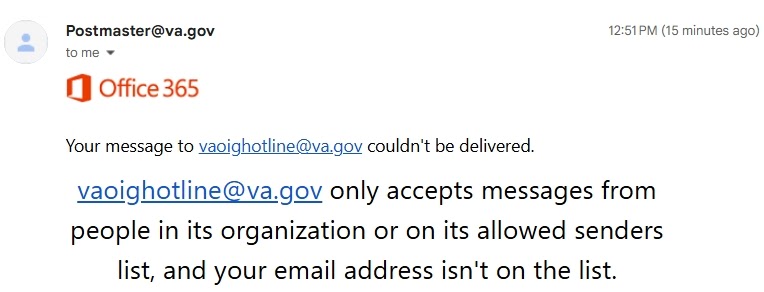

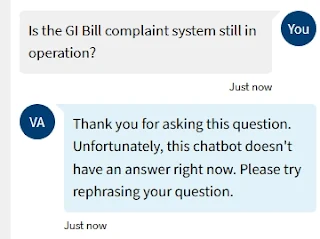

These reforms are meant to widen access, yet direct entrants often slip through the cracks in registry systems, appearing only as “continuing”, unknown to academics. If we can’t even see them on the map, how can universities hope to guide or support them?

Behind from day one

Direct entrant students are those who join a degree at a later point (typically level 5 or 6). They will often have completed a foundation degree or Higher National Diploma (HND) at a partner college, or transferred from another university straight into their second or third year.

While universities have built entire transition strategies around first year students, the challenges faced by direct entrants are often similar – yet intensified by the social and institutional disorientation of joining an established cohort partway through their studies. I remember sitting in my first lecture and realising that everyone already knew the academic language, the course structure, and even the referenced to earlier modules. It wasn’t just a gap in content for me, it was a gap in belonging.

The human side of higher education comes first for many students, whether that is finding friends, feeling confident, or above all feeling part of their course and institution, and this is the essential starting point for academic success, as shown in a recent systematic review. Belonging is not just a buzzword. It shapes how students engage, stay motivated and ultimately succeed. Its role is especially significant in a sector where learners’ backgrounds and pathways are increasingly diverse. If belonging is a prerequisite for success, then direct entrant students begin their journey at a clear disadvantage.

The data illustrates this: in 2015–16, only 48 per cent of direct entrants achieved a good honours degree, compared with 61 per cent of those who started from the beginning, a 13 per cent gap that rarely receives the same attention as other attainment gaps, according to research by Sarah Cuthbert. The absence of more recent data highlights that direct entrants remain largely overlooked in research. Recognising these challenges points to a clear question: what can universities do to ensure direct entrants are seen, supported and set up to succeed?

What needs to change

To better support direct entrant students, universities need targeted interventions that recognise their distinct journey.

Early identification in registry systems (simple direct entrant tick box/field at enrolment ensuring they are flagged from day one), paired with intentional support from personal academic tutors would make these students visible and allow their progress to be tracked. Providing direct entrants with pre-term communications, including module options, progression pathways, and summaries of previous year’s content can help them feel prepared and settle into their studies more smoothly.

Building on this, tailored inductions that acknowledge the unique needs of these students could build confidence, social connections, and a sense of belonging from day one. Peer mentoring schemes, where current direct entrants support newcomers, offer practical advice and reassurance, helping to reduce isolation and bridge cultural gaps between FE and HE. Such interventions align with the white paper’s recommendations for smoother progression routes and closer collaboration between colleges and universities.

Despite ongoing financial pressures universities are facing, these interventions are cost-effective and achievable. They build on systems universities already have and simply require adaption to ensure direct entrant students are recognised and supported. By adjusting structures, communication, and support to fit the students, rather than expecting students to adapt to rigid systems, universities can improve outcomes, retention, and overall experience for a cohort too often unseen.

With application numbers falling across many institutions, universities have every incentive to recognise and strengthen all routes into university. Lower than expected recruitment is already widely forecast to leave many providers facing deficits. This makes it even more urgent to ensure that direct entrants are visible and well supported. There is a clear need to reduce barriers between courses and levels, and in doing so strengthen non-traditional pathways while enhancing attainment, continuation and overall student experience, especially at a time when these metrics are under such close scrutiny.

A test of our priorities

Universities often say they want to support all students to succeed, but direct entrants put that promise to the test. They represent the diversity of routes into higher education, and as policymakers push universities to show real improvement in outcomes and participation, their experiences highlight whether commitments to inclusion are actually being delivered in practice. When I started my career in student engagement, I noticed the same gaps in practice. These gaps were not the result of the institution trying to be exclusive, but rather blind spots built into processes designed for first year students.

Recent work from Student Minds highlights the need for institutions to adapt to their students, rather than expecting students to assimilate into complex, inflexible structures. To achieve true inclusion, universities must reconsider their practices, ensuring every student, regardless of entry point, can transition smoothly into both learning community.

If universities fail to do so, the white paper’s vision of flexible, module pathways and integrated tertiary provision risks remaining theoretical rather than practical. If we are serious about building systems that work for all students, direct entrant students can no longer remain invisible.