Higher education is seeing a surge of interest in non-degree credentials. Learners are seeking faster, more affordable pathways to workforce advancement. Employers are increasingly open to (and in some cases requesting) alternatives to traditional degrees. And with new federal policy expanding Pell Grant eligibility to non-degree programs, institutions are feeling the urgency to act.

But not all certificate programs are created equal. And while the trend line is clear, the strategy behind how institutions respond is anything but. This moment presents an opportunity, but only for those willing to plan with purpose and set realistic expectations.

What’s driving demand for short-term credentials?

Recent data underscores a clear increase in interest:

- Undergraduate certificate enrollment grew 33% and graduate certificate enrollment grew 21% from Fall 2020 to Fall 2024, according to National Student Clearinghouse data.

- Google search volume for certificates has increased 19% from 2020 to 2025, according to Google Trends data.

Today’s learners are drawn to programs that offer accelerated timelines, reduced costs, and clear pathways to meaningful career outcomes. Many working adults are looking to upskill or pivot careers, and a certificate can be a more practical option than a full degree.

On the employer side, organizations want proof of skills and are increasingly willing to collaborate with institutions on curriculum design. In fact, according to a 2022 employer survey from Collegis and UPCEA, 68% of respondents said they would be interested in teaming up with an institution to develop non-degree credentials to benefit their workforce.

Certificates are a piece of the puzzle — not the whole strategy

Despite the interest, many institutions struggle to meet enrollment goals for certificate programs. Strong market trends do not automatically translate into high enrollment volume. The reality is that most certificates serve niche audiences and deliver modest numbers. When treated as stand-alone growth drivers, they often fall short.

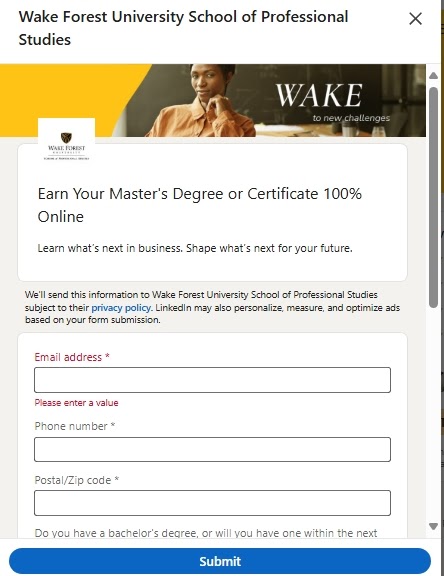

The institutions that see the most strategic value from certificates do so by positioning them within a larger enrollment and academic ecosystem. For example, we’ve helped our partner institutions find success in using certificate interest as a marketing funnel to drive engagement in related master’s programs. Once a prospective student engages, enrollment teams can advise them on the best fit for their career goals, which, for some students, is enrolling in the full degree program.

Ready for a Smarter Way Forward?

Higher ed is hard — but you don’t have to figure it out alone. We can help you transform challenges into opportunities.

What a strategic certificate model looks like

A certificate program with purpose isn’t just a set of courses — it’s a product with clear value to both learners and the institution. Key elements of a strategic approach include:

- Workforce alignment: Programs must be rooted in real-time labor market data. What skills are employers seeking? Which certifications are valued? Aligning with reputable industry certifications is a proven way to ensure relevance and employer recognition.

- Accessibility: Pricing should reflect the certificate’s value relative to degree programs, and eligibility for financial aid must be prioritized. Lack of aid is a significant barrier to enrollment for many prospective learners.

- Laddering and stackability: Certificates should not be terminal unless intentionally designed that way. They should stack into larger degree pathways or offer alumni incentives for continuing their education.

- Delivery speed and flexibility: Busy adult learners expect quick starts, clear outcomes, and minimal red tape. Institutions need streamlined onboarding and agile curriculum design.

- Internal collaboration: Designing certificates in isolation often leads to friction. Academic, enrollment, and marketing teams must be aligned on purpose, target audience, and outcomes.

- Employer engagement: Employers want to be part of the development process and seek assurance that certificate programs teach the skills they need. Their involvement enhances the recognition and credibility of the credential.

The role of institutions: Balance mission with market

Certificate programs are not a shortcut to growth. But they can be a smart strategic lever when grounded in data and designed to complement an institution’s broader mission. They offer colleges and universities an opportunity to:

- Expand access to underserved learners

- Respond more nimbly to labor market shifts

- Strengthen ties with regional employers

- Drive awareness and enrollment for degree programs

The key is alignment. When certificate offerings reflect both market demand and institutional mission, they can play a powerful role in expanding reach and impact.

Plan with purpose, execute with intent

Certificates are more than just a trending credential. They’re a tool to serve learners in new ways. But institutions must resist the urge to chase quick wins. Success requires thoughtful design, realistic expectations, and cross-functional collaboration.

With the right foundation, certificate programs can do more than fill a gap. They can open doors for learners, employers, and institutions alike. Collegis supports this effort with integrated services in market research, instructional design, and portfolio development — empowering institutions to make informed, mission-aligned decisions that deliver impact.

Innovation Starts Here

Higher ed is evolving — don’t get left behind. Explore how Collegis can help your institution thrive.