Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Colorado officials say money that helps 18,000 low-income families pay for child care could run out by Jan. 31 if federal officials don’t lift the freeze they’ve imposed on funding for several safety net programs in five Democrat-led states.

If that happens, some children could go without care and some parents would have to stay home from work. State lawmakers could cover such a funding gap temporarily, though Colorado is facing a significant budget crunch.

The Trump administration announced the freeze on $10 billion in child care and social services funding for Colorado, California, Illinois, Minnesota, and New York in a press release Monday.

In letters sent to the two Colorado agencies that run the affected programs, federal officials said they have “reason to believe that the State of Colorado is illicitly providing” benefits funded with federal dollars to “illegal aliens.”

The letters didn’t cite evidence for that claim and a spokesperson for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services didn’t respond to questions from Chalkbeat about why federal officials are concerned about fraud in Colorado.

Spokespeople from both state departments said by email on Tuesday they’re not aware of any federal fraud investigations focused on the programs affected by the funding freeze.

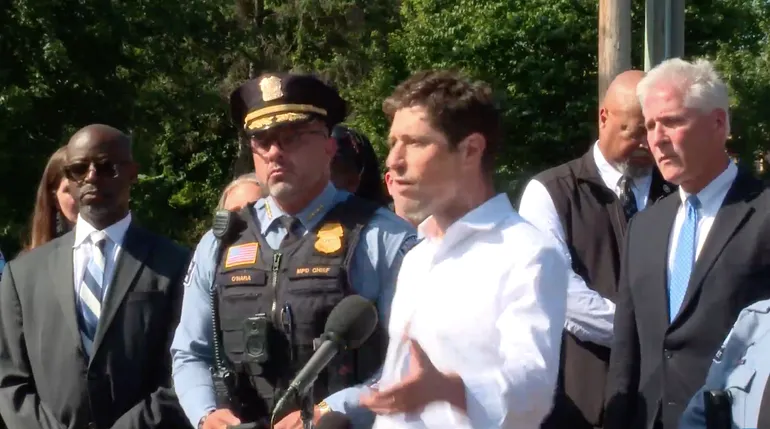

The five-state funding freeze follows a federal crackdown in Minnesota after a right-wing YouTuber posted a video in late December alleging that Minneapolis child care centers run by Somali residents get federal funds but serve no children. It’s not clear why the other four states have gotten the same treatment as Minnesota, but all have Democratic governors who have clashed with President Donald Trump.

In a New Year’s Eve social media post, Trump called Colorado Gov. Jared Polis “the Scumbag Governor” and said Polis and another Colorado official should “rot in hell” for mistreating Tina Peters, a Trump supporter and former Mesa County clerk who’s serving a nine-year prison sentence for orchestrating a plot to breach election systems.

The federal freeze will affect three main funding streams in Colorado that together bring in about $317 million a year. They include $138 million for the Colorado Department of Early Childhood for child care subsidies for low-income families and a few other programs.

The subsidy program, known as the Colorado Child Care Assistance program, helps cover the cost of care for more than 27,000 children so parents can work or take classes. It’s mostly funded by the federal government with smaller contributions from states and counties.

The other two frozen funding streams go to the Colorado Department of Human Services and pay for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, or TANF, and other programs.

In the letter to the Colorado Department of Early Childhood, federal officials outlined new fiscal requirements the state will have to follow before the funding freeze is lifted. They include attendance documentation — without names or other personal identifiers — for children in the child care subsidy program.

A state fact sheet issued in response to the funding freeze said funding for the child care subsidy program would be depleted by Jan. 31. It also outlined several measures already in place to prevent fraud or waste, including state audits, monthly case reviews by county officials, and efforts to recover funds if improper payments are made.

The state said it is exploring “all options, including legal avenues” to keep the frozen funding flowing.

Six Democratic state lawmakers, most in leadership positions, released a statement Tuesday afternoon calling the funding freeze a callous move that will make life more expensive for working families.

“We stand ready to work with Governor Polis and partners in our federal delegation to resist this lawless effort to freeze funding, and we sincerely hope that our Republican colleagues will put politics aside, get serious about making life in Colorado more affordable, and put families first,” the statement said in part.

The statement was from Speaker of the House Julie McCluskie; Senate President James Coleman; House Majority Leader Monica Duran; Senate Majority Leader Robert Rodriguez; Rep. Emily Sirota; and Sen. Judy Amabile.

Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools.

Did you use this article in your work?

We’d love to hear how The 74’s reporting is helping educators, researchers, and policymakers. Tell us how