The lead reviewer of Australia’s universities Mary O’Kane has outlined what the Universities Accord missed during her address at the University of Sydney 2025 Bradley Oration .

Please login below to view content or subscribe now.

Membership Login

The lead reviewer of Australia’s universities Mary O’Kane has outlined what the Universities Accord missed during her address at the University of Sydney 2025 Bradley Oration .

Please login below to view content or subscribe now.

This blog was kindly authored by Rose Stephenson, Director of Policy and Strategy at HEPI.

It is the ninth blog in HEPI’s series responding to the post-16 education and skills white paper. You can find the others in the series here, here, here, here, here, here, here and here.

There have been oodles of column inches already published about the Post-16 White Paper, and many have rightly focused on the headlines: increased tuition fees, a return of targeted maintenance grants funded by an international students levy and a move towards more specialist institutions.

In this blog, I want to dive beyond these headlines, as the paper contains a number of further bold policy proposals, some of which could be transformational for the sector.

The White Paper places a strong focus on flexible learning, including a greater number of Level 4 and 5 qualifications. There is a specific target of at least 10% of young people going into Level 4 or 5 study, including apprenticeships, by 2040. Clearly, the Government wants to see more movement in this direction from the sector, adding:

We need to build clear and well-understood pathways at these levels [4 and 5], underpinned by qualifications that are easier to study close to home, which are both modular and flexible.

In terms of higher education providers, the Government sets out:

We will expect providers to offer more flexible, modular provision and strengthen progression routes from further education into higher education, supported by transferable credits. We will consult on making student support for level 6 degrees conditional on the inclusion of break points in degree programmes. This marks a significant shift towards a more inclusive and adaptable model of learning, empowering individuals to tailor their educational journey.

There is little detail, but it reads to me that the Government will consult on a proposal that students will only be able to access student loan funding for institutions that offer ‘break points’ at Level 4 and 5 of a full three-year degree.

This was also a recommendation from the Augar report, which outlined:

… providers with degree-awarding powers will be required to offer them [level 4 and 5 qualifications] as ‘exit’ qualifications if learners choose to leave a course early.

In my experience, most institutions now do this. If a student wants or needs to finish their studies at the end of their first year, for example, (providing they have passed the required modules), the institution would offer to award them with the Level 4 qualification that recognises their learning to date – most likely a certificate of higher education. However, ‘CertHEs’ are only routinely awarded ‘mid-degree’ if a student withdraws, and many students don’t know that there is an option to take a qualification at the end of their first year. One might wonder if providers could maintain this ‘consolation prize’ status quo. However, the paper goes further, stating:

The introduction of break points will ensure that learners are acquiring vital, usable skills in every year of higher education. It will give them the option to break down their learning, achieving a qualification at level 4 after the first year and level 5 after their second year of studies, while also ensuring institutions are incentivised to support those who wish to continue their studies. This will enable young people to ‘stay local and go further’ by connecting local provision at level 4 and 5 with internationally recognised degree-level providers, unlocking opportunity and ambition across every region.

I am reading between the lines here, but it looks as though providers may be expected to award students at the end of each year of learning, increasing awareness of stackable, flexible learning, and potentially a knock-on increase in student mobility between institutions. As with much of this White Paper, we await the details.

The white paper outlines:

We will work with the sector and others so that the supply of student accommodation meets demand, including increasing the supply of affordable accommodation where that is needed. We will work with the sector, drafting a statement of expectations on accommodation which will call upon providers to work strategically with their local authorities to ensure there is adequate accommodation for the individuals they recruit.

Firstly, this statement is a little ironic given that the Renters Reform Act that has just passed through parliament is likely to reduce small (generally one to two bedroom) off-street student housing provision – as outlined by Martin Blakey in his blog.

This feels woolly to me. What levers does the Government have to pull to increase the supply of affordable accommodation for students? If it does have any, why have these not been pulled already? The main driver of expensive student accommodation is that there are not enough houses (for the general population as well as students), allowing rents to be driven ever higher. Providers working strategically with local authorities won’t deliver more housing stock. (Unless the magic house bush grows alongside the magic money tree?)

We’ve seen a ‘Statement of Expectations’ previously, delivered by the OfS in relation to sexual harassment prevention and response on campus. This was an evaluated stepping stone on the way to regulation. Could there be an increased expectation on institutions to provide affordable accommodation as part of future regulation? A sensible ideology, perhaps. After all, we know students want and need cheap places to live. But given the financial position of many institutions, the resulting pause in capital building projects, the increase in commuter students and the impending decline in 18-year-old population numbers, I can’t see many subsidised student flats being built anytime soon.

We have known since before the 2024 General Election that Labour wanted to expand the Apprenticeship Levy to become the Growth and Skills Levy. We see some more detail about this in the paper:

We want employers to be able to use the levy on short, flexible training courses.

Currently, apprenticeships are funded by the apprenticeship levy. Businesses with a pay bill of over £3 million pay 0.5% of this into the levy ‘pot’. Businesses can then use the levy fund to cover the cost of training apprenticeships. Since the introduction of the levy, the number of apprenticeship starts has fallen, and the age profile of apprenticeships has changed. Since 2015, proportionately more apprenticeships have been started by those aged 25 or over.

Source: Department for Education, Apprenticeships and traineeships data

So – the apprenticeship levy was, unintentionally, a good policy for lifelong learning; businesses wanted to reinvest their levy costs into their business and found that an effective way to do this was to upskill colleagues already employed in their organisation, often on higher or degree apprenticeships. The flip side of this meant that the intended outcomes of the policy, supporting school and college-leavers into apprenticeships, were stymied.

To tackle this, most Level 7 Apprenticeships were defunded, with the aim of pushing funding back towards younger learners and lower-level apprenticeships. So the move to ‘apprenticeship units’ feels undermining of this aim. Again, this is likely to be great for lifelong learning. Employers will be able to upskill their workforce, initially in ‘priority areas’ such as artificial intelligence, digital and engineering.

There is a limited pot of growth and skills levy funding, which has been fully or overspent for the last two academic years. So if the Government wants to increase apprenticeships for younger learners, it will need to expand this pot, and potentially ring-fence some of this. The potential for a bigger pot is hinted at:

We will work with businesses and employers over the coming months to ensure that the growth in skills levy author is developed to help meet their needs and incentivise further employer investment in training.

However, ring-fencing is not mentioned. The Government will need to put some guardrails in place here if they want to meet their target of two-thirds of young people going to university, further education or a ‘gold standard apprenticeship’ by the age of 25.

So, while some of these statements are bold, remember that White Papers set out proposals for future legislation; there is a long way to go before legislation is in place. Further, there are several places in the white paper where the Government doesn’t specifically propose legislation; instead, there’s a sense of just asking the sector nicely. This is all well and good, but in times of severe financial constraint, asking institutions nicely to take steps that will cost them money is unlikely to yield results.

This story was originally published by Chalkbeat. Sign up for their newsletters at ckbe.at/newsletters.

I didn’t expect to grieve.

I knew taking a central office role meant trading the school building for a district badge. I knew the days would be filled with policy, meetings, and personnel issues. What I didn’t know was how much I would miss morning announcements, front office chatter, and the small but sacred chaos of classroom life.

When I accepted my central office role at Knox County Schools nearly three years ago, I heard words of congratulations and encouragement, and a lot of “You’ll be great at this.” What I didn’t hear was, “You’re going to miss the cafeteria noise” or “You’ll feel phantom pain for your walkie and reach for it like it’s still there.” No one warned me I’d find myself lingering too long during school visits, trying to feel like I still belong.

What I lost wasn’t just proximity; it was identity.

As a principal, I was part of everything. Students shouted greetings across the parking lot. Parents stopped me in the grocery store to ask about bus routes or share weekend news. Teachers popped into my office with questions or just to drop off a piece of cake from the lounge. I wasn’t above the work. I was in it. I was woven into the messy, beautiful rhythm of a school day.

Shifting to the central office changed not just the pace of my day, but the feel of the work. The space was quieter, the communication more deliberate. There are no morning announcements. No car rider line and morning high-fives from kids. No spontaneous TikTok dances during class change. I moved from the rhythm of a living, breathing school to a place where school leadership feels more technical, more filtered, and more removed.

The relationships changed, too. As a principal, you’re not just part of a team; you’re a part of a family. You laugh together, carry each other’s burdens, and share both the stress and the wins. Move into a district role, and you’re now “from downtown,” even if your heart still lives on campus. You walk into buildings with a badge that means something different, and the conversations shift just enough for you to notice.

None of this means the central office work doesn’t matter. It does. Or that I don’t love it. I do. Central office work gives me a systems-level view of how our schools function. I find purpose in improving not just individual outcomes, but the structures that guide them.

Still, the change in relational gravity caught me off guard. And once the initial disorientation passed, it left me with a deeper concern: How will I stay connected to how the work is actually experienced and carried out in schools if I’m no longer living in it each day?

At first, I told myself it was just a learning curve, that it would pass, that I’d find new rhythms soon enough. And I did — but not before realizing that central office leadership requires a different kind of muscle. One I hadn’t needed before.

As a principal, I lived in fast feedback loops. I saw the effects of my decisions by lunchtime. I knew which teachers were having a hard week, which student needed extra eyes, which parent was about to call. Even hard conversations came with a certain clarity because I was close to the context and knew the culture I wanted to build.

At the district level, the impact is broader but harder to track. The wins take longer to see. The feedback is quieter.

I had to become more intentional about noticing what I could no longer see. That meant listening differently during school visits, paying closer attention to what leaders were navigating, and asking better questions. Not just about what was happening, but what it was costing them to make it happen.

One of the advantages of working at a systems level is being able to recognize patterns across multiple settings. They can reveal root causes that individual concerns might never expose. That clarity opens the door to more aligned, lasting support.

I began thinking less about whether expectations were clear and more about whether they were sustainable. My role was not to direct the work but to support the people carrying it out.

These changes didn’t come naturally. They came because I didn’t want to become a leader who made good decisions in theory but stayed out of touch in practice. I didn’t want to lead by spreadsheet, even though color-coded tabs bring me great joy. I wanted to lead by understanding.

Eventually, I began to see that even though I was no longer in the thick of the school day, I could still choose to stay connected — to show up, to ask real questions, to build trust not just through policy, but through presence.

The classroom educators and school leaders I supported didn’t need someone who had knowledge of what it was like to be a teacher or principal. They needed someone who remembered what it felt like to be one. Someone who hadn’t forgotten the rush of the morning bell or the weight of a tough parent meeting or the impossible feeling of juggling school culture, teacher evaluations, instructional priorities, and a leaky roof all before noon.

I think back often to my first year in central office. The silence. The absence of bells and kids and chaos. The invisible weight of missing something no one warned me I would lose. I remember walking through a school one afternoon and instinctively reaching for my walkie talkie. It wasn’t there. Of course it wasn’t there. But the reflex reminded me of something important: I still wanted to be tuned in.

Leadership doesn’t have to grow lonelier as it grows broader. But staying connected takes intention. It takes habits, not just memories.

I didn’t expect to grieve. But I’m grateful I did. Because grief has a way of reminding you what still deserves your presence.

Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools.

For more news on district management, visit eSN’s Educational Leadership hub.

We’ve covered elsewhere the implications for policy related to academic freedom and freedom of speech stemming from the Office for Students’ decision to fine the University of Sussex for breaches of ongoing registration conditions E1 and E2.

The publication of a detailed regulatory report also allows us insight into the way in which OfS is likely to respond to future breaches of registration conditions. It is, effectively, case law on the way OfS deals with concerns about higher education providers in England – and while parts of your university will be digesting what the findings mean for academic freedom policies, others will be thinking more widely about the implications for regulation.

The University of Sussex, perhaps unsurprisingly, wishes to challenge the findings. It is able to challenge both the regulatory decisions and the amount of the fines at a first tier tribunal.

As always, appeals are supposed to be process based rather than just a general complaint, so the university would have to demonstrate that the application of the registration conditions was incorrect, or the calculation of the fine was incorrect, or both. As above, there is no meaningful defence of the way the fines were calculated or discounted within the judgement so that would feel like the most immediately fertile ground for argument.

Here’s some of the points that stood out:

We are told that, on 7 October 2021, the OfS identified reports about an incident at the University of Sussex. This followed the launch of a student campaign at the University of Sussex the previous day – which involved a poster campaign, a masked demonstrator holding a sign, and a hashtag on social media – calling for Kathleen Stock (a professor in the philosophy department) to lose her job.

This was widely covered in the media at the time, and sparked commentary from interest groups including the Safe Schools Alliance UK and the Free Speech Union. The OfS subsequently contacted the university seeking further information, before starting a full investigation on 22 October 2021. However, despite significant public interest, the decision to start an investigation was not made public until a statement by an education minister in the House of Lords on 16 November (when we were told that the Department for Education was notified on 11 November).

Kathleen Stock resigned from her role at the university on 28 October – six days after the start of the investigation, and substantially before the public announcement. She noted that “the leadership’s approach more recently had been admirable and decent”, while the university claimed to have “vigorously and unequivocally defended Prof Kathleen Stock’s right to exercise her academic freedom and lawful freedom of speech, free from bullying and harassment of any kind”.

What’s not clear from this timeline is the nature of the notification on which the Office for Students was acting: the regulatory framework in place at the time suggested OfS would take action on the basis of lead indicators, reportable events, and other intelligence and sources of information. There are no metrics involved in this decision, and we are told the provider did not notify the OfS so there was no reportable event notification.

We are left with the understanding that “other sources of information” were used – these could be “volunteered by providers and others, including whistleblowers”. Perhaps it was the same “source of information” that caused then Minister Michelle Donelan to shift from backing the university response on 8 October to calling for action on 10 October?

We also know that – despite OfS’ insistence that it “does not currently have a role to act on behalf of any individual” – it appears that the only person to submit a “witness statement” to OfS was Stock. If OfS was concerned generally about the potential for a chilling effect on academic speech, would it not want to speak to multiple academics to confirm these suspicions? Doesn’t speaking to just one affected individual feel a little like acting “on behalf” of that individual?

Finally – sorry to bang on – we don’t know who at OfS made the decision to conduct an investigation or on what basis. Can, say, the director of regulation just decide (based on a story in the press, or general vibes) to investigate a university – or is there a process involving sign-off by other senior staff, ideally involving some kind of assessment of the likelihood of a problem being identified within a reasonable period of time? If I were an internal auditor I would also want to be very clear that the decision was made using due process and free from political or ideological influence (for instance I’d be alarmed that someone was content for then-chair James Wharton to posit an absolutist definition of free speech in the Telegraph) shortly after the investigation started.

The only clue we are given in the regulatory report is that this is a “complex area”. OfS requested a substantial amount of documentation from Sussex – it even used a “compliance order” to make sure that no evidence was destroyed. However, it does not appear that OfS ever visited the provider to speak to staff and students – in other regulatory investigation reports, OfS has been assiduous in logging each visit and contact. There is none of that here – we don’t know how many interactions OfS had with Sussex, or on how many occasions information was requested. Indeed, OfS appears not to have visited Sussex at all. Arif Ahmed told us:

“There may have been occasions where the university wanted to meet in person and communication was done in writing instead

Various points of law are referred to in the regulatory report : it is notable that none of this is new law requiring additional interpretation or investigation (the new Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Act had not even left the House of Commons committee stage at this point). It shouldn’t really take a competent lawyer that knows the sector more than a few weeks to summarise the law as it then stood and present options for action.

The investigation into the University of Sussex was mentioned in the Chief Executive’s report from the 2 December 2021 Board meeting, and it turned up (often just as an indication that the investigation was ongoing)

Well, quite. On our reckoning, the Act would have made no difference to the entire affair, save potentially for a slight chilling effect on students being empowered to exercise their own freedom of speech, and a requirement for both providers and OfS to promote free speech. The ability of the OfS to reach the conclusion it reached, and to instigate regulatory consequences, suggests that further powers were not necessary to uphold freedom of speech on campus – despite the arguments made by many at the time. There is nothing OfS could have done better, or quicker, or more effectively had the Act been in force. Sussex, in fact, had a freedom of speech policy at the time, something that the regulatory report fails to mention or take account of.

It is curious that the announcement of the investigation came at the start of a long pause in parliamentary activity on the Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Act – at that time we were keenly anticipating a report from the House of Commons committee stage, but we got no action at all on the bill until it was carried forward into the next session of parliament.

There is a detailed account of the process by which it was decided to fine Sussex £360,000 for a breach of registration condition E1, and £225,000 for a breach of registration condition E2. It appears thorough and convincing, right until the point that you read it.

OfS appears to be using a sliding scale (0.9 per cent of qualifying income for “failing to uphold the freedom of speech and academic freedom governance principle”, 0.5 per cent of qualifying income for “a failure to have adequate and effective management and governance arrangements in place”, an additional 0.2 per cent for not reporting the breach, a 0.2 per cent reduction for taking mitigating action…) and although Regulatory Notice 19 takes us through the process in broad terms we don’t get any rationale for why those proportions apply to those things.

It’s all a bit “vibes based regulation” in truth.

It is to be welcomed that OfS reduced its initial calculation of a £3.7m (1.6 per cent of qualifying income) fine to a more manageable £585,000 – but why reduce to that amount (by a hair under 85 per cent) purely because it is the first fine ever issued for this particular offence? What reduction will be applied to the next fines issued under registration conditions E1 and E2? If none, why not – surely “sufficient deterrence” is possible at that amount so why go higher?

The documentation covers none of this – it is very hard to shake the impression that OfS is pulling numbers out of the air. When you compare the £57,000 (0.1 per cent) fine issued to the University of Buckingham for not providing audited accounts for two years (something which would have yielded something altogether nastier from Companies House you do have to ask whether the Sussex infractions were 1.5 percentage points more severe at the initial reckoning?

There are so many questions raised that will now be hurriedly posed at universities and higher education all over England – and my colleague Jim Dickinson has raised many of them elsewhere on the site. He’s had enough material for four pieces and I’m sure there will be many more questions that could be explored. Why – for example – should the regulator have a problem with “prohibiting the harmful use of stereotypes”? Is there a plausible situation where we would want to encourage the harmful use of stereotypes?

It would also be worth noting the many changes to the policy that appears to have caused the initial concern (the Trans and Non-Binary Equality Policy Statement) between 2018 and 2024. Perhaps these changes demonstrated the university dealing with a rapidly shifting public debate (conducted, in part, by people with the political power to influence culture more generally) as seemed appropriate at each point? So why is OfS not able to sign off on the current iteration of this policy? Why is it hanging a hefty fine on a single iteration on what is clearly a living document?

There’s also a burden issue.Is it the position of the regulator that every policy of each university needs to be signed off by the academic council or governing bodies? Or are there any examples of policies where decisions can be delegated to a competent body or individual? A list would be helpful, if only to avoid a burdensome “gold plating” of provider-level decision making.

There are 24 ongoing conditions of registration currently in force at the Office for Students – a regulatory report and a fine (or other sanctions) could come about through an inadvertent breach of any one of them. Many of these conditions don’t just apply to students studying on your campus – they have an applicability for students involved in franchised (and in some cases validated) provision around the world.

We should be in a position where the sector can be competently and reliably regulated, where providers can understand the basis, process, and outcomes of any investigation, and that these are communicated promptly and clearly to the wider public. On the evidence of this report, we are a long way off.

Ahead of a House of Lords debate on the topic of lifelong learning later this week, today’s blog features two posts on the topic.

Elsewhere on the site, Professor Harriet Dunbar-Morris, Pro Vice-Chancellor Academic and Provost at The University of Buckingham, highlights what is, in her view, a critical flaw in the LLE: the unfair funding gap facing students on accelerated two-year degree programmes, despite their clear benefits for employability and skills development. You can read that piece here.

And below, Dr. Michelle Morgan explores the gaps in the Government’s Lifelong Learning Entitlement (LLE), questioning why postgraduate taught courses have been left out and what this means for students, universities, and businesses.

So the Government has announced that the Lifelong Learning Entitlement (LLE) will come into effect in September 2026.

The government is arguing that the LLE will allow people to develop new skills and gain new qualifications at a time that is right for them. The LLE will focus on:

It is argued that it will help drive sustained economic growth, break down barriers to opportunity broaden access to high-quality, flexible education and training, and support greater learner mobility between institutions.

However, yet again the sector’s postgraduate taught (PGT) provision has been ignored. By excluding this level of study, the ambitions of the Government will not be as great as they could be, and it is a huge, missed opportunity for higher education and this is why.

In the past 10 years, the higher education sector has increasingly relied on international master’s students to fund itself. EU and non-EU PGT students are nearly all undertaking master’s degrees, whereas for UK-domiciled students, a master’s degree only constitutes around 55% of those on PGT courses. Taught courses include master’s, postgraduate certificates, diplomas, and institutional credits and postgraduate certificates in education.

For Master’s participation, 2019/20 was a pivotal year as non-EU participation surpassed UK-domiciled for the first time. In each year since 2021/22, UK-domiciled Master’s enrolments have declined (see Table 1). Although we do not have Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) return data to view for 2022/23 and 2023/24, there is a strong sense across the sector that we will see a decline in master’s participation, especially among international students.

Source: Who’s studying in HE? | HESA

The decline is the same pattern that occurred leading up to 2010/11. The only reason why master’s participation continued to increase then was due to non-EU enrolments. The response by the Government to re-energise the UK-domiciled market after the Higher Funding Council for England’s (HEFCE, which was then the regulator) Phase 1 and 2 of the Postgraduate Support Scheme was to bring in the Postgraduate Loan. As soon as this happened, you could hear an audible sigh of relief across the sector, and there was an attitude of ‘that will solve the problem so let’s just focus on growing the master’s market’. The sector did not consider the demand for master’s qualifications by business and industry, especially small and medium enterprises (SMEs).

There are disciplines where a master’s is required for career progression such as professional accreditation. However, as the 11 University Postgraduate Experience Project found, which was one of 20 projects funded as part of the HEFCE Phase 1 Postgraduate Support Scheme, many SMEs did not need master’s graduates. Most useful to them was for higher education to provide short courses and modules that provided their staff with advanced skills in key areas such as Business and IT and emerging ones such as Generative AI. According to the Department for Business and Trade’s report on Business population estimates for the UK and regions in 2024, there were 5.6 million UK businesses in 2024 of which 5.5 million were SMEs, accounting for 99.8% of all businesses. By ignoring the needs of business and industry, we are losing an opportunity to engage with a critical market.

As soon as the Postgraduate Loan was introduced, most universities immediately raised their fees. The aim of the £10,000 loan was to cover fees and some maintenance. Although the loan for September 2024 English starters is now £12,471, for many this will not come close to covering their costs. What is also not factored into any discussion is that someone who has both an undergraduate and a postgraduate loan must pay them back concurrently. This equates to 9% for the undergraduate loan and 6% for the postgraduate, or 15% of someone’s salary on top of tax, National Insurance and any other employee-related costs. Although employers’ national insurance contributions are increasing next year, if there is any tax or National Insurance increase for the individual next year, this will further reduce their disposable income.

The Postgraduate Loan also differs between UK countries. In England, the loan does not cover stand-alone postgraduate certificates and diplomas, unlike in Scotland, where non-master’s postgraduate taught course participation is 56% compared to 44% in England. If they were included, then maybe the LLE as it stands would not be quite as restricted. The English loan system is not agile enough to support engagement in short or non-master’s courses, and English universities plan their finances for master’s enrolments and anticipated completions. A student should not have to register and enrol on a master’s if they only want or need to do a postgraduate certificate or diploma. If an individual needs a master’s for professional accreditation, this will not stop them from doing a master’s. In fact, we may see an increase in integrated degrees being undertaken where a master’s is incorporated into the undergraduate degree as a result.

Additionally, we have just had the announcement that undergraduate loans are slightly increasing, but no announcement has been made for postgraduate loans. The current system hinders engagement. It also adopts a deficit model approach, as these qualifications are deemed exit qualifications if someone fails to achieve the Master’s.

What is also overlooked in discussions are the debt levels of undergraduate alumni and how this could explain the decreasing number of UK-domiciled 21-24-year-old participants. The majority of PGT enrolments are for the age group of 30 years and over.

Source: Who’s studying in HE? | HESA

When the Postgraduate Loan was introduced in 2016, only one cohort had graduated under the £9,000 a year fee regime introduced in 2012. We now have 10 cohorts who graduated under that regime. It is maybe not a surprise therefore that the largest group investing in postgraduate taught study are those with the smallest amount of undergraduate debt.

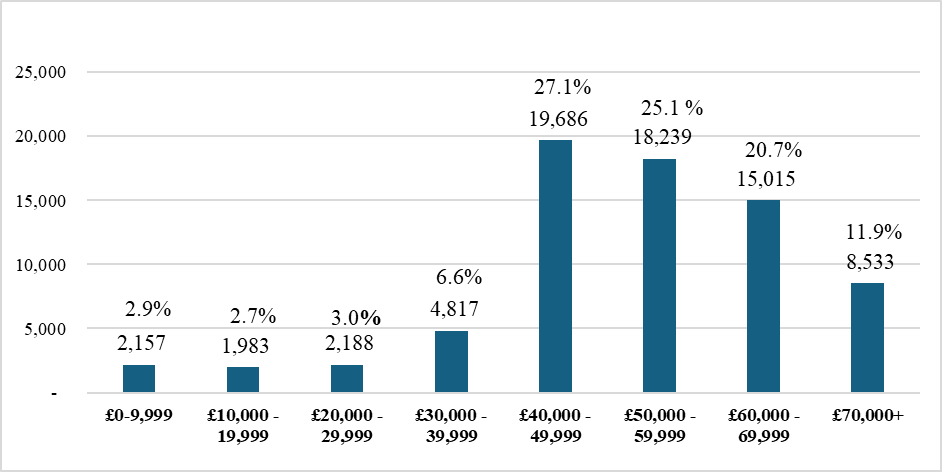

Last year, I got the results of a Freedom of Information request from the Student Loan Company regarding the debt levels for English-domiciled recipients entering postgraduate Master’s study in 2021/22 (see Figure 1). Of the 72,618, 74.8% had debt in excess of £40,000 and 11.9% over £70,000. This debt will include any repeated years as well as longer length undergraduate courses such as integrated degrees with placements. With the recent announcement that fee levels will rise by £285 to £9,535 in 2025/26, this will increase individual debt.

Figure 1: Debt levels of 72,618 English-domiciled master’s students who also have an undergraduate loan (fee and maintenance) in 2021/22 only

The recent Times and Sunday Times showed how parental financial support differs by student groups and universities. The universities where parents pay the most – up to £30,000 – are mainly Russell Groups. And when you explore postgraduate taught participation by ethnicity, 66% are White. How will the factors highlighted above enable widening participation at the postgraduate level which delivers advanced skills, competencies and knowledge?

The LLE that will be introduced will not super-proof the pipeline for longevity of postgraduate taught study nor provide the advanced skills that are accessible, meaningful and needed for the individual, society or business and industry.

So we need to start thinking now about the long-term implications of student debt, and social and economic needs so we can develop policy, strategy and practice. To do this though, the sector needs to start thinking about how we can reimagine and do things differently, Government needs to listen to key stakeholders, and we must proactively work together and not against one another.

by CUPA-HR | January 4, 2023

Throughout the year, the Higher Ed Workplace Blog and Higher Ed HR Magazine feature HR innovations and success stories from the CUPA-HR community. In case you missed them, we’ve listed several great blog posts and articles of 2022 that will leave you feeling inspired and ready to take action at your institution.

Okay, so you’re feeling inspired after reading these HR success stories, but now you’re wondering how you can get to work at your institution. These CUPA-HR resources can help you take that next step!