Much of the controversy around the Trump administration’s “Compact for Academic Excellence in Higher Education” has focused on its push for viewpoint diversity and the claim that open inquiry does not exist in our classrooms. That push builds on a long-standing conservative critique that today makes hay out of the fact that the vast majority of faculty in U.S. colleges and universities lean left.

Recent data supports that claim. In elite institutions, like Duke and Harvard Universities, surveys suggest the number of faculty identifying as liberal exceeds 60 percent. The percentages differ not only by type of institution but by discipline, with the humanities and social sciences leaning more liberal than STEM. Some even claim that political bias corrupts academic disciplines.

Liberal faculty and commentators on higher education sometimes take the bait and respond defensively to what often is a politically motivated attack. In an op-ed in The Guardian, Lauren Lassabe Shepherd argued that the purpose of the conservative critique has been “to delegitimize the academy … [and] return colleges to a carefully constructed environment not to educate all, but to reproduce hierarchy.”

Whether or not she is right, you don’t have to look hard to see that institutions of higher education are feeling growing pressure to right their ships—to create campuses and classrooms where open inquiry flourishes, where students feel free to say what they think and to challenge ideas they disagree with. Colleges have responded by scrambling to incorporate more ideological diversity into their course offerings, to implement new programming and to recruit guest speakers who challenge progressive thinking.

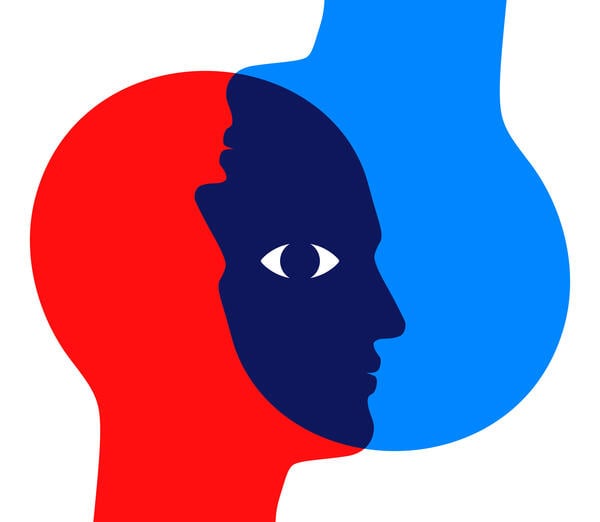

All this misses the point and distracts us from the work that needs to be done to further improve the quality of the education students receive in American colleges and universities. Put simply, instead of fixating on who is in the classroom and whether they are liberal or conservative, we should be focused on how we are in the room.

Higher education’s greatest challenge to achieving open inquiry is not one of ideology or viewpoint diversity, but of disposition. Harvard University’s 2024 report from a working group on open inquiry gestured in this direction but did not flesh it out.

If we are to truly commit to open inquiry, we need to step back, pause and reflect not just on what we think, but on how we acquire knowledge, how we think, whether we are interested in learning more or if we are content with what we already know.

You can decorate campuses with all the colors of the political rainbow but not make them better places to learn.

The issue is how we show up with others. Data suggests that students in our classrooms don’t feel comfortable pushing back on each other or on their professors when they disagree. They engage in what psychologists Forest Romm and Kevin Waldman call “performative virtue-signaling.”

In conversations with students at Amherst College, we have heard that they are not just constraining their expression in academic settings but in social settings, too. It seems we are afraid of each other.

It is no wonder. The academic and public squares have not proven themselves to be especially kind or generous as of late. We need look no further than the vitriolic reactions to Charlie Kirk’s murder, and the as-vitriolic reactions to the reactions to his murder. When we do, we can see that the rush to righteousness operates across the ideological spectrum.

The work of college education is to dislodge the instinct to judge and replace it with a commitment to rigorous listening. The work of college teachers is to model an approach to the world that puts empathy before criticism.

What if instead of just talking about the right to speech, we emphasized the right to listen? But we don’t just mean any kind of listening; we mean listening in a certain way. Deep listening. The kind of listening that takes in ideas in slow, big gulps and lets them settle deeply, and sometimes uncomfortably.

It is listening that seeks to catch ideas in flight and carry them further. This is a disciplined kind of listening that resists defensiveness and instead burrows into curiosity.

To foster it, we have to cultivate in ourselves and in our students a disposition to wonder. Why does someone think that way? What experiences, places, relationships, institutions and social forces have shaped their thinking? How did they get to that argument? How did they get to that feeling? How is it that they could arrive at a different perspective than I did?

This is the heart of open inquiry, and it is much harder to achieve than it is to bring more conservatives to campus. Without the disposition to wonder, doing so will produce enclaves, not engagement, on even the most ideologically diverse campus.

This kind of open inquiry would demand that we remove the stance of moral certainty and righteousness from our ways and practices of thinking. That is the real work that needs to animate our colleges and universities.

It is hard, slow work. There is no magic bullet. Teachers and their students, liberals and conservatives, have to commit to it.

While open inquiry is a social disposition, it is also about how we orient our thinking when we are alone. We need to challenge our students to wonder not just about others but about themselves.

What would happen if we all got into the habit of asking ourselves: When was the last time we changed our mind about something? When was the last time we left a conversation or finished a text and actually grappled with our orientation to a subject?

We yearn for our students to practice open inquiry not just when they are in our classrooms, but when they are in the library or in their dorm room with a book to read, an equation to solve, a painting to finish.

The promise of this type of inquiry is exhilarating, freeing. And it opens up great possibilities of seeing the world differently or in more complicated ways.

At the end of the day, the literary scholar Peter Brooks gets it right when he says, “To honor, even only nominally, the call for ‘viewpoint diversity’ is to succumb to a logic that is at its heart hostile to the academic enterprise.” At the heart of that enterprise is a belief that viewpoint diversity is not the same thing as open inquiry. That belief requires changing the culture of learning on our campuses.

Maybe the shift does not seem responsive to the political clamor of the moment. Maybe it sounds like it demands too much and will be hard to assess.

But whatever the case, it feels revolutionary to us.