The debate about duty of care in higher education has been obscured by the repeated collapse of distinct legal questions into a single, unresolved argument.

In particular, discussion of whether a duty of care exists is routinely conflated with questions about what responsibility would require in practice.

That confusion has prevented sustained analysis of the standards by which conduct should be judged, which is where responsibility acquires real content.

To address that problem, this article deliberately limits the scope of its analysis. It does not engage with the minimal, background obligation that applies to everyone not to cause foreseeable and substantial harm to others.

That obligation is universal and requires very little: it is ordinarily satisfied by avoiding obvious risks in everyday activity, and it doerobert as not involve the design of systems, the monitoring of risk, or the anticipation of harm beyond what is immediately apparent.

Nor does this article seek to resolve the threshold question of whether, and in what precise circumstances, an overarching institutional duty arises in higher education. That question turns on context and relationship and can be answered in different ways as a matter of law.

This limitation is adopted for a reason. Disputes about the existence or outer boundaries of duty tend to obscure the more significant and unresolved issue of how responsibility should be exercised in practice.

The analysis proceeds on the assumption that, as in other recognised institutional and professional contexts, a relationship-based duty may arise where organisations undertake defined functions and create foreseeable risks through their systems and decision-making.

On that assumption, the central question is not whether duty exists, but how it should be discharged. The focus is accordingly on the standards by which responsibility should be assessed in a modern university, rather than on analogies or models of conduct borrowed from different fields.

Duty establishes responsibility; standards give it content

In law, a duty and the standard by which conduct is assessed perform different functions. The duty establishes that responsibility arises at all. It is a gateway concept, triggered where there is a sufficient relationship and a risk of foreseeable harm.

Once a duty exists, it doesn’t prescribe outcomes or require the provision of any particular form of “care” in the everyday sense of that word. Rather, it establishes that those with responsibility must avoid carelessness in their actions or inaction, including in how systems are designed and how decisions are taken where foreseeable harm may arise.

What counts as reasonable, and therefore what amounts to carelessness, is not determined by the existence of the duty itself, but by what is reasonably required in the circumstances, having regard to the role performed, the functions undertaken, and the context in which decisions are made.

The practical consequences of this distinction are straightforward but often overlooked. Responsibility does not take a single, uniform form. What it requires depends on the nature of the activity undertaken, the role being performed, and the degree of reliance and risk created in the circumstances. The same underlying obligation not to act carelessly will therefore be expressed very differently in different settings.

Crucially, it also requires that foreseeable risks are addressed rather than deferred – responsibility is not discharged by ignoring warning signs, postponing decisions, or allowing procedural drift to substitute for timely action where intervention is reasonably required.

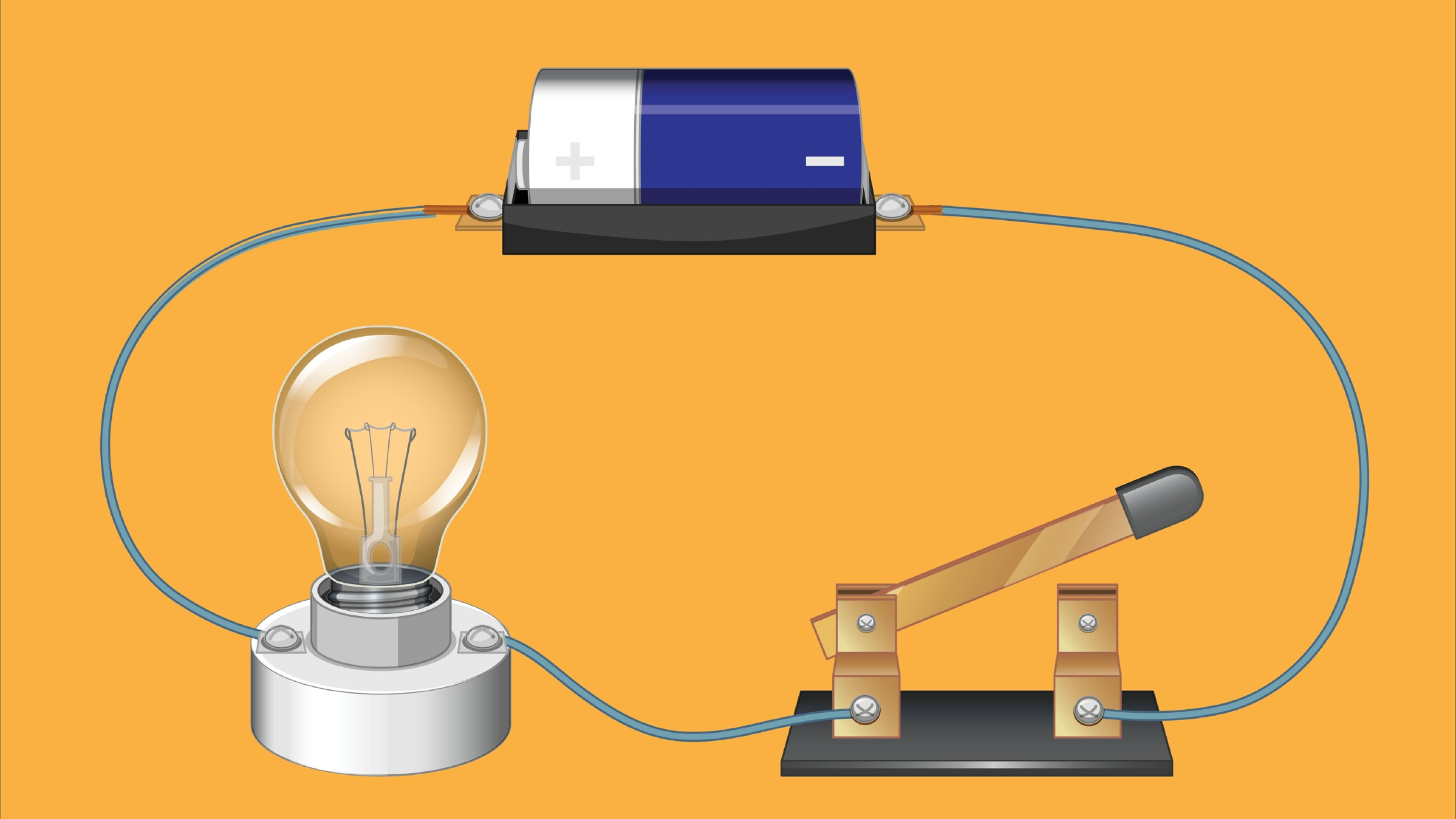

The distinction is often easiest to see through the lens of professional systems. A stranger has no obligation to warn you of an approaching storm. An airline, by contrast, has invited you into its system and possesses the radar to see the danger. It can’t stop the storm, and it’s not your parent – but it does have a responsibility arising from how it manages risk.

Borrowed standards obscure, rather than clarify, responsibility

Discussions of responsibility in higher education are frequently derailed by the use of inappropriate comparisons.

When questions are raised about what universities should reasonably be expected to do, the response is often to reach for an existing and familiar model from elsewhere – parenting, custody, clinical practice, or institutional supervision. These comparisons are then used to argue that universities either cannot, or should not, be held responsible in similar ways.

This mode of argument rests on a basic mistake. It assumes that responsibility must always be understood by analogy to some other established setting, and that the only question is which existing model should be imported (never mind that none of them quite fit). The result is a debate conducted by comparison rather than analysis, in which standards developed for very different purposes are treated as benchmarks against which responsibility in higher education is judged.

The problem is not that these other standards exist. It is that they are being used in the wrong way.

One obligation, assessed differently across contexts

Across the law, there is not a proliferation of different duties corresponding to different institutions. In each case there is an underlying obligation not to act carelessly where responsibility arises. What varies is how that obligation is assessed in different contexts. The law doesn’t ask whether an institution resembles a parent, a prison, or a hospital. It asks what avoiding careless conduct reasonably requires, given the role performed, the functions undertaken, and the risks created.

Standards developed in other settings reflect those settings. Parental and apprenticeship standards arose where there was dependency and close supervision. Custodial standards reflect confinement and control. Clinical standards reflect specialist expertise, regulation, and professional judgement. Each provides a way of judging conduct in its own context. None is a universal template, and none can be transplanted wholesale into a different institutional environment without distortion.

Using these standards as analogies for higher education therefore tells us very little about what universities should reasonably be expected to do. At best, such comparisons show what higher education is not. They don’t tell us what it is.

In loco parentis explains the past – it does not define the present

The continued invocation of in loco parentis illustrates this problem clearly. Parents owe a duty to their children, but they are judged according to a parental standard shaped by dependency, authority, and control. In loco parentis did not create a special or additional duty. It applied that parental standard to educational institutions at a time when students were young, dependent, and subject to close supervision.

The difficulty today is not that universities are being asked to revive this model. It is that in loco parentis is still treated as a reference point, either to be defended or rejected, rather than as a historical example of how responsibility was once assessed in very different circumstances. Once that is recognised, arguments about universities “becoming parents” lose their relevance. The parental standard is neither applicable nor required.

Control calibrates responsibility – it does not create it

Control is often introduced at this point as a decisive factor. Universities, it is argued, do not exercise the level of control found in prisons, hospitals, or schools, and therefore should not be subject to responsibility of any comparable kind. This argument again mistakes comparison for analysis.

Control doesn’t determine whether responsibility arises. It influences what avoiding careless conduct reasonably requires. Where control is extensive, expectations are correspondingly more intrusive. Where control is partial or situational, expectations are more limited. Where control is absent, responsibility may still arise, but its practical demands will be constrained. This is how responsibility already operates across institutional contexts, including prisons, hospitals, and schools.

Control, in this sense, isn’t all-or-nothing. A university doesn’t control where a student chooses to walk late at night, but it does control the lighting on its own campus paths. Responsibility attaches to what falls within that sphere of influence, and the standard is calibrated accordingly.

The same reasoning applies to higher education providers. The question is not whether they resemble other institutions, but how responsibility should be assessed having regard to what they actually do, how they are organised, and the risks their systems and decisions create.

In professional systems, responsibility includes designing processes that can respond when risk escalates beyond routine conditions. Where systems lack clear escalation pathways, or where exceptional circumstances cannot override ordinary procedure, responsibility may fail not through indifference, but through inertia. Standards of care are tested not only by what institutions do in normal conditions, but by whether their systems enable timely and proportionate action when those conditions no longer apply.

Seen in this light, comparisons with parents, prisons, or hospitals do not advance the debate. They obscure it. Higher education doesn’t need to borrow someone else’s standard in order to avoid responsibility, nor to justify it. What is required is a clear articulation of the standard that fits higher education as it exists now, rather than as it once did or as something else entirely.

A professional standard in practice

Modern universities are professional institutions operating through differentiated roles, delegated expertise, and organisational systems. Avoiding carelessness in this context doesn’t require staff to act beyond their competence. Academic staff are not clinicians, and non-academic staff are not responsible for making safeguarding judgements beyond their role.

Clarity of role is not a threat to academic freedom but a condition of it. By defining where responsibility properly sits, academic staff are protected from being pressed into quasi-clinical or pastoral roles for which they are neither trained nor authorised, allowing them to focus on teaching and scholarship while institutional systems manage risk. Academic freedom is therefore not incompatible with responsibility – it depends on responsibility being allocated clearly and appropriately.

What avoiding careless conduct does require is that roles are clearly defined, that concerns are recognised and escalated appropriately, and that institutional systems are designed to manage foreseeable risk without leaving responsibility to chance. Harm frequently arises not from dramatic acts, but from omissions – fragmented information, unclear responsibility, or decisions taken without regard to known risk. These are questions of institutional competence rather than individual moral failing.

The difference between a parental approach and a professional one can be illustrated simply. Under a parental standard, a student’s unexplained absence might prompt direct personal intervention – phone calls, door-knocking, or demands for explanation. Under a tertiary professional standard, responsibility is exercised differently.

The focus is not on intrusion, but on systems – whether attendance data, engagement with digital resources, or other indicators trigger an appropriate institutional response in line with defined roles and protocols. The question is not why the student has disengaged, but whether the institution’s systems are functioning competently to recognise and respond to foreseeable risk.

Naming the Tertiary Professional Standard

The standard by which responsibility in higher education should be assessed can be described as the Tertiary Professional Standard. This term identifies the particular way in which responsibility is judged in the higher education context, reflecting its professional, role-sensitive, and institutional character.

It is neither parental, custodial, nor clinical. It aligns responsibility with competence and control, reflects the realities of adult education, and recognises that universities act through systems as well as individuals. The Tertiary Professional Standard protects students without infantilising them, and it protects staff by defining the limits of what can reasonably be expected.

It replaces confusion with clarity. Higher education doesn’t need to revive outdated models or deny responsibility altogether. It needs to articulate, clearly and honestly, the standard by which responsibility is already exercised. That is the conversation now worth having.