For several years, I’ve been providing content and student support for the University of Kentucky’s Changemakers program, designed and managed by the Center for Next Generation Leadership. It’s an online one year continuing education option where Kentucky educators can get a rank change for successful completion. I appreciate that Next Gen believes in “parallel pedagogy”; while it provides valuable resources and materials to be read, viewed, and reflected on, it also requires the program’s students to complete meaningful transfer tasks, pursue an action research project, and participate in a final defense of learning that demonstrates how transformative practices are happening in the Changemaker’s own classroom.

This professional learning pathway to rank change involves mostly asynchronous work through online modules focused on the awareness and implementation of what Kentucky calls “vibrant learning” in the classroom, with module topics such as Learner Agency and Inquiry Based Learning. It’s my contribution to the latter module where the content below originally began, but I’ve expanded and added more detail for this blog entry.

Inquiry-based learning is a powerful pedagogy. For students, it can be as extensive as working on a multi-week project-based learning unit, or as simple as asking more high-quality questions in class. Inquiry comes from curiosity, and the attempt to answer challenging questions and solve problems that have no obvious solution.

Keep in mind that traditionally, and for decades (centuries!), you have been considered to be the expert in the room – of your content, of your pedagogy, of your ability to manage your classroom. The professionalism required of the vocation, much less the idea of professional standards boards that grant, review, and in some cases revoke certification to teach, adds to the foundational belief that a teacher has earned their well-deserved “expert” credentials.

But you are usually one human in a room of thirty. Leaning into the expertise of your students can be at its most basic level a strategy of smartly leveraging your numbers. Viewing your classroom through an asset mindset, we can see students as learners that bring their own powerful POVs which can enrich your culture and community. For example, with the right scaffolding, structures, and practice, your students are capable of providing peer-to-peer feedback.

However, some of our stumbling blocks in education are self-induced, born out of a desire to remain humble. For example, calling yourself or anyone else an “expert” can sound or feel lofty and divisive. Educators are sometimes their own worst critic, and may wonder aloud what right they have to declare themselves the expert on such-and-such. As for students, they may view their own bountiful and beautiful knowledge with a shrug of their shoulders. If someone in middle school knows how to disassemble and reassemble a car engine, it simply reflects their personal interests, or the fact that their mother loves hot rods. They are told early and often in traditional school that such knowledge isn’t “book learnin’.” Loving hot rods or diesel mechanics doesn’t matter, thinks the student, because it’s not a part of my third period class, and it won’t show up on my multiple choice test on Friday.

Therefore, let’s consider a broadening of our definition of “expert,” and look more at the first five letters of the word. What we really hope to provide, increase, articulate and bring into a classroom is experience. From another person’s POV, your experience may be long and traveled (which can make you “more experienced”), or simply a road I’ve never traveled upon (which makes your experience a novel one, compared to mine). Viewing expertise in this kind of inclusive light opens up what an “expert” is. We can see an expert as simply (but powerfully!) a person with a different, valued perspective. The key word is “valued.” You may have a different POV, you may have twelve degrees on the wall, but if I don’t care about you and especially if you don’t care about me, your “expertise” won’t matter much. We can also see an expert as a person who is recognized as skillfully applying knowledge. The key word is “applying.” Remember that old chestnut that answers the question, “What’s the difference between intelligence and wisdom?” Intelligence is knowing that a tomato is a fruit, but wisdom is knowing you would never put a tomato in a fruit salad. Expertise that feels too detached and theoretical, or a bunch of random facts you can Google anyway, won’t personally matter very much to your learners.

You might have noticed that artificial intelligence wasn’t mentioned above as a potential “outside expert.” Going back to our expanded definition, it certainly can seem to checkmark the same boxes. AI can offer a different perspective, powered by code and fueled by billions of artifacts from our culture and knowledge. Is that perspective valued, or valuable? It might, although AI is not always accurate, unbiased, or trustworthy; however, the same can be said of Wikipedia entries created by humans, or the theory from a popular scientist of the past which has been discredited in the present. Discernment and critical thinking is key, particularly from the teacher who should be monitoring, filtering, and observing the AI usage (and teaching students to be critical AI users as well). AI can also certainly apply its knowledge scraped across the terabytes of the Internet within (milli)seconds of being prompted. Is that knowledge skillfully applied? Based on the uploaded rubric of a teacher alongside the first draft of a student’s essay (being mindful of your platform’s privacy protections, of course), or the public domain text of an author, AI could provide nuanced feedback on student writing or pretend to be a character in a book for a fascinating interactive conversation. But some of the proficiency of AI’s application will depend on qualitative measures: of the rigor of the rubric you uploaded, or the veracity and bias of the knowledge it grabbed from its database, or the depth of skills the AI has been taught to emulate. And again, AI hallucinations can happen.

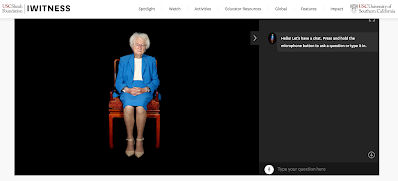

When prompted, a short video plays where the interviewee “answers” your question, creating a virtual conversation. You can do this via your microphone or by typing. What may seem miraculous is really just clever programming – the interviews were transcripted and time-coded, so AI simply takes your prompt, scans the text, finds a corresponding clip that seems to best answer your question, and plays from that particular time-stamped portion of the interview. Still, you can see the power of providing such “expertise” to students, giving them a chance to be both empathetic as well as practicing their questioning/prompting skills. (It should also be noticed the dignity and care given to the subject matter by USC and Shoah. The interviews were real, using genuine survivors of genocide and the Holocaust, not actors. While you technically could have AI “pretend” to be a survivor of a war crime as a customized chatbot, or have students interact with some kind of digital fictionalized Holocaust survivor avatar, there are many reasons why this would be an unethical and inappropriate use of such technology.)

As you ponder ways to increase and improve inquiry, reflect on the nature of “expertise,” both inside and outside of your own four walls. As you do so, you can cautiously consider how AI can be one of many types of “outside experts” you can bring into your classroom.