Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

A week after Florida health officials brought the state one step closer to abolishing childhood vaccine mandates, pediatricians, parents and advocates are expressing alarm over the ramifications.

If such a change goes into effect, “pediatric hospitals will be overwhelmed with [childhood] infections that have virtually been non-existent for the last 40 years,” said Florida-based infectious disease specialist Frederick Southwick. Southwick attended a Dec. 12 public comment workshop on the issue hosted by the Florida Department of Health.

“We’re in trouble right now,” he added, pointing to falling vaccine rates and the likelihood that some diseases could become endemic. “We’re getting there, and this [ending the mandate] would just do-in little kids.”

The session delved into the proposed language the department has drafted for a rule change that would do away with vaccine mandates for four key immunizations: varicella, more commonly known as chickenpox; hepatitis B, pneumococcal bacteria and Haemophilus influenzae type B, or HiB. Currently, children cannot attend school in Florida without proof of these four immunizations, among others, including the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine.

Although Florida is not considering removing the mandate for the MMR vaccine, health experts see the move it is contemplating as eroding childhood immunization generally. It comes when more than 300 people are being quarantined in South Carolina because of a burgeoning measles outbreak.

Rana Alissa, president of the Florida Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics, was also in attendance to express her concerns. She told The 74 this week that thanks to the success of vaccines, she’s never had to treat some of these “horrible diseases,” including HiB, which can lead to meningitis.

“Don’t make our kids — Florida’s kids — guinea pigs to teach me and my classmates and other pediatricians how to manage these diseases,” she implored.

Tallahassee parent Cathy Mayfield lost her 18-year-old daughter, Lawson, to meningitis in 2009, a few months before she was supposed to leave for college and just before she was due for a booster shot. (At the time, the booster was not recommended until college, according to Mayfield.)

“You just don’t realize until it happens to you,” she said.

She hopes others will learn the importance of vaccinating their own kids from her family’s story.

“All the information I learned through our tragedy about vaccinations made me very supportive of the safeguards [they] offer,” she said.

“You’ve also got to realize,” Mayfield added, “that your decisions affect your community, and that’s something I think has gotten lost in … all this conversation and hesitancy about vaccinations.”

Equating vaccine mandates to slavery

The workshop, which was announced the day before Thanksgiving, was held in Panama City Beach, in the Florida Panhandle, far from the state’s main population centers. About 100 people showed up to the session, which was characterized by attendees as heated but civil. Northe Saunders, president of the pro-vaccine advocacy organization American Families for Vaccines and who was there, estimated that about 30 people spoke in favor of keeping the current vaccine mandates, while approximately 20 spoke in opposition.

Some speakers opposed to vaccine mandates included conspiracy theories in their arguments, according to news reports and numerous people present at the workshop, echoing language heard from the federal government since Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a long-time vaccine skeptic, took over the Department of Health and Human Services.

One attendee argued that giving children multiple jabs in a 30-day period “accounts to attempted murder,” according to NBC News. A number of others questioned if this year’s reported measles outbreaks, which resulted in the deaths of two school-age, unvaccinated children in Texas, had actually occurred.

Florida leaders’ desire to become the first state to end all vaccine mandates was announced in September by its surgeon general, Joseph A. Ladapo, standing beside Gov. Ron DeSantis in the gym of a private Christian high school. In sharing their plan, Ladapo claimed that “every last [mandate] is wrong and drips with disdain and slavery.”

Only four vaccines are mandated through a Department of Health rule and are therefore under Lapado’s purview. The remaining nine, which in addition to the MMR shot include polio, are part of state law and can only be changed through legislative action.

Experts told The 74 this is a much more difficult feat, one that state legislators — even conservative ones — don’t seem to have an appetite for. Richard Hughes, a George Washington University law professor and leading vaccine law expert, said such a legislative attempt would “warrant legal action.”

‘We really need to turn this around’

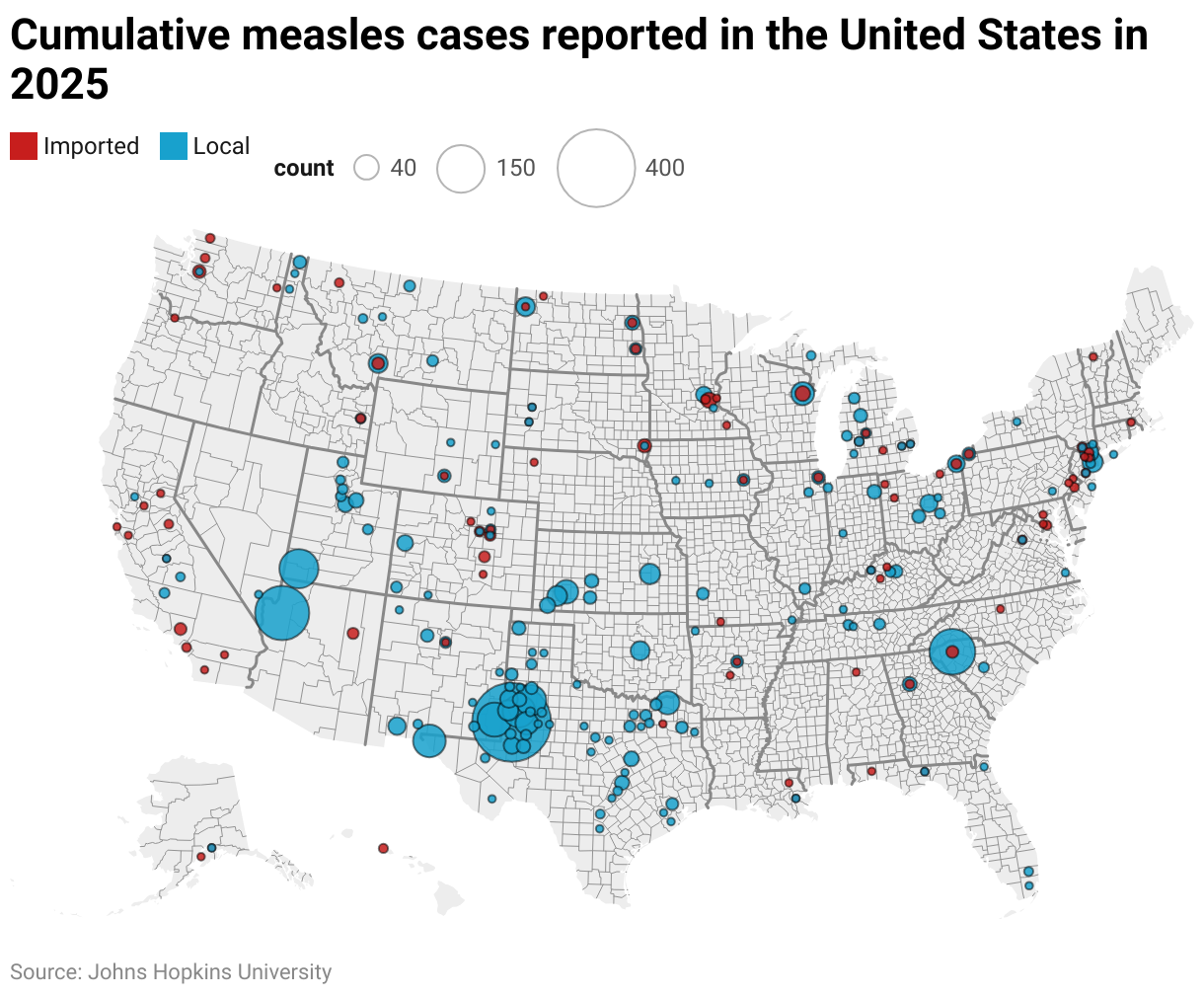

The debate in Florida and other states over mandatory childhood immunization comes as the country teeters on the edge of losing its measles elimination status. This year alone has seen nearly 2,000 confirmed cases, the most since 2000, when measles was declared eliminated in the U.S. by the World Health Organization. Just over 10% of cases have led to hospitalization. The current South Carolina outbreak has infected at least 138 people, and among those forced to quarantine are students from nine schools.

Significant educational implications from the outbreaks emerged in a new study by the Annenberg Institute at Brown University, which found that absences increased 41% in a school district at the center of the West Texas outbreak, with larger effects among younger students.

The spread of measles is also a warning of the ramifications of dropping vaccine rates, according to William Moss, executive director at Johns Hopkins’ International Vaccine Access Center.

“Measles often serves as what we [call] the canary in the coal mine,” he said. “It really identifies weaknesses in the immunization system and programs, because of its high contagiousness.”

“Unfortunately, I see a perfect storm brewing for the resurgence of vaccine preventable diseases,” he added, “… We really need to turn this around.”

Earlier this week, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention got rid of a recommendation that all newborns receive the hepatitis B vaccine, and in the preceding months changed policies surrounding the measles, mumps, rubella and varicella (chickenpox) combination vaccine and this year’s COVID 19 booster — all based on recommendations from an advisory committee hand-picked by Kennedy. The universal birth dose of the hepatitis B vaccine, in place for decades, was credited with nearly eliminating the highly contagious and dangerous virus in infants.

Lynn Nelson, the president of the National Association of School Nurses, fears that other, more conservative states will now look to Florida as an example.

“We already have seen outbreaks all over, and they’re only going to escalate if you have an area of the country whose herd immunity levels slip down further than they already are, which I think will happen if those [anti-mandate rules] come into effect,” she said. “That, in combination with some of the other misinformation that’s coming out, people will feel validated in decisions not to immunize their children.”

Florida’s Department of Health appears to be moving ahead to end requirements for the four vaccines it controls, despite a recent poll indicating nearly two-thirds of Floridians oppose the action. Proposed draft language presented at the Dec. 12 workshop would also allow parents to opt their kids out of the state’s immunization registry, Florida SHOTS, and expand exemptions.

Currently, all 50 states have vaccine requirements for children entering child care and schools. Parents across the country are able to apply for exemptions if their child is unable to get vaccinated for medical reasons and most states — including Florida — also have religious exemptions. Part of the proposed changes presented at the Dec. 12 meeting would add Florida to the 20 states that additionally have some form of personal belief exemptions, further widening parents’ ability to opt their kids out of routine vaccines.

The public comment period remains open through Dec. 22, after which the department will decide whether or not to move forward with the rule change. In the interim, advocates are pushing state health officials to conduct epidemiological research around the impact of removing the vaccine mandates and studies on the potential economic costs. Florida is heavily reliant on tourism and out-of-state visitors.

Without that information, pro-vaccine advocate Saunders said these critical public health care decisions will be made “at the whim of an appointed official.”

“The nation,” he added, “is looking at Florida.”

Did you use this article in your work?

We’d love to hear how The 74’s reporting is helping educators, researchers, and policymakers. Tell us how