The nine universities that were sent the Trump administration’s new deal for higher ed are under increasing pressure to reject the compact.

Multiple major associations representing institutions and faculty have urged them not to sign it. California governor Gavin Newsom has said the University of Southern California and any other university in his state that signs will “instantly” lose billions of state dollars. Faculty groups at the University of Virginia, another institution presented with the compact, overwhelmingly urged university leaders to reject it. A group of progressive student and higher ed worker organizations is circulating a petition that calls on university presidents and boards to “reject the Trump administration’s attempt to cajole universities into compliance through explicit bribery.”

So far, the universities at the center of the fight are remaining mostly mum, saying they’ll review the proposal. Some leaders are hinting they have reservations about signing. But other higher ed leaders and observers say that beyond what those institutions do, the nine-page document represents another escalation in the White House’s precedent-shattering crusade to overhaul postsecondary ed—one that could restrict freedoms at colleges across the nation. They expect the compact will likely serve as a blueprint for the administration’s dealings with other colleges.

“It’s making it really clear that the dominoes are being set up … they’re going to expand this to the rest of higher ed,” said Amy Reid, interim director of PEN America’s Freedom to Learn program.

A White House official told Inside Higher Ed in an email that “other schools have affirmatively reached out and may be given the opportunity to be part of the initial tranche.” The New York Times cited May Mailman, a White House adviser, as saying the compact could be extended to all institutions.

The administration has dangled the compact before universities with promises of extra benefits it hasn’t revealed. It’s an evolution in the White House’s quest to upend higher ed using the blunt instrument of federal funding access. The federal government earlier slashed billions of dollars from Harvard and Columbia Universities and other selective institutions to pressure them to change their internal policies and practices.

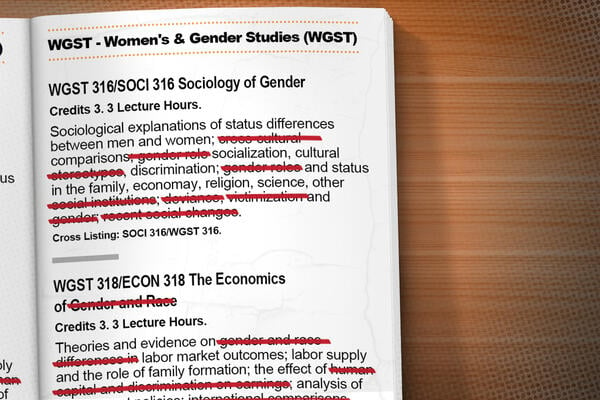

But now, the administration has written a boilerplate contract asking colleges to voluntarily agree to overhaul or abolish departments “that purposefully punish, belittle, and even spark violence against conservative ideas,” without further defining what those terms mean. It also asks universities to, among other things, commit to not considering transgender women to be women and to reject foreign applicants “who demonstrate hostility to the United States, its allies, or its values.”

In addition to a murky promise of additional money, the compact can be read as threatening colleges’ current federal funding. Higher ed groups say those that sign are taking a big gamble. The compact says failure to adhere to the terms of the agreement, which are vague, can lead to a loss of all federal funding. But it’s also unclear whether the universities have the freedom to refuse. A line at the end of the compact’s introduction says, “Institutions of higher education are free to develop models and values other than those below, if the institution elects to forego [sic] federal benefits.”

The nine institutions sent the Compact for Academic Excellence in Higher Education aren’t necessarily being asked to sign it. The letter sent to the University of Virginia requested “limited, targeted feedback” on the compact by Oct. 20—before the White House sends invitations to finalize language and sign to universities showing “a strong readiness to champion this effort.”

Lynn Pasquerella, president of the American Association of Colleges and Universities, said many campus leaders worry that, if any institutions do sign the compact, it will start a ripple effect in which other university leaders feel pressured to sign so they don’t lose out on funding.

Joy Connolly—president of the American Council of Learned Societies, a federation of 81 groups including the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Historical Association—added that with this compact, the White House “is using nine months of intimidation tests to take its divide-and-conquer strategy to the next level.”

“If one by one institutions give in and sign, hoping to mitigate the damage later, it will set a truly problematic precedent,” Connolly said. “Some of the most powerful and wealthy institutions on the planet will have agreed to subject their faculty and research and teaching to state approval, and academia will be visibly divided into an insider group and an outsider group.”

Unclear Carrots, Clearer Sticks

According to the letter to UVA—signed by Mailman, Education Secretary Linda McMahon and Vincent Haley, director of the White House’s Domestic Policy Council—universities that sign will reap “multiple positive benefits … including allowance for increased overhead payments where feasible, substantial and meaningful federal grants, and other federal partnerships.” The White House didn’t provide Inside Higher Ed further information on how much extra money signatories would be able to receive.

The compact itself makes no mention about the potential financial benefits of signing.

For this unclear gain, a signatory university would risk all of their federal funding: The compact says “all monies advanced by the U.S. government during the year of any violation shall be returned to the U.S. government.”

Asked to clarify whether a university that refuses to sign could lose all federal funding, White House spokeswoman Abigail Jackson replied in an email simply that “the Administration does not plan to limit federal funding to schools that sign the compact.”

Jackson said universities that do sign “would be given [funding] priority when possible as well as invitations to collaborate with the White House. This is an opportunity for collaboration that all institutions of learning should be excited about.” The White House didn’t grant Inside Higher Ed an interview or answer written requests for more information about the compact’s benefits and how some of its requirements should be interpreted.

Pasquerella, of AAC&U, said the compact is “meant to be vague as a way of fomenting confusion.”

“Part of the strategy, I believe, of this administration is to engage in overly broad, overly vague language that is confusing so it’s not clear when institutions are complying,” Pasquerella said—a form of jawboning that pressures universities to overcomply. She said the compact’s promise of federal funds for signatories and apparent threat of cuts for those who refuse is “not a real choice.”

“It is the continued weaponization of federal funding,” she said. The compact isn’t “reforming higher education but dismantling it and replacing it with institutions that have a conservative ideology.” It disadvantages those institutions that are unwilling to relinquish their academic freedom and other freedoms, such as transgender people’s rights, she said.

Jon Fansmith, senior vice president for government relations at the American Council on Education, expressed concern that institutions that don’t sign could face the same “harassment” Harvard has suffered for refusing the administration’s earlier demands on that university. The administration cut off Harvard’s access to billions of dollars in research funding, placed it on heightened cash monitoring and tried to prevent it from enrolling international students, among other efforts in a growing pressure campaign against the institution.

“Now they’re essentially saying we’re going to create two classes of institutions,” Fansmith said: those “swearing fealty to the administration” and getting extra benefits, and those that are punished.

“That’s a massive step in the wrong direction in the history of American higher education,” he said. He said prioritizing less merit-worthy candidates for federal funding just because they signed the compact is “harmful to the goal of getting the best science performed on behalf of the American people.”

Standing Up

Fansmith noted the compact’s ideas aren’t necessarily new for the administration, but they would add up to “very specific intrusions into institutional policies.” For instance, the compact would mandate that all “undergraduate applicants take a widely-used standardized test … or program-specific measures of accomplishment.” Signatories must also agree that no more than 15 percent of their undergraduates be in the “Student Visa Exchange Program [sic], and no more than 5 percent shall be from any one country.” (The Student and Exchange Visitor Program, not the Student Visa Exchange Program, collects information on international students.)

Reid, of PEN America, said, “The administration has gone from picking off individual schools to selecting a group—a group of well-respected universities, but that for different reasons are seen as perhaps likely to comply—and putting everyone on notice that this is coming for everyone.”

Some of the nine institutions, however, have hinted at reservations about signing. On Friday, Dartmouth College president Sian Leah Beilock noted in a statement that “you have often heard me say that higher education is not perfect and that we can do better. At the same time, we will never compromise our academic freedom and our ability to govern ourselves.”

On Sunday, University of Pennsylvania president J. Larry Jameson said Penn’s “long-standing partnership with the federal government in both education and research has yielded tremendous benefits for our nation,” but also that “Penn seeks no special consideration.” On Monday evening, University of Virginia Board of Visitors chair Rachel Sheridan and interim president Paul Mahoney wrote in a message to the campus community that “it would be difficult for the University to agree to certain provisions in the Compact.”

Reid told Inside Higher Ed that “for those of us who are not at those nine targeted institutions, the question is how do we all respond in a way that bolsters the resolve of any institution to stand up.”

“It is wrong to call this a compact, because there’s nothing mutual about it,” Reid said. “It is a one-sided coercive proposition that has a bow of commonality stuck onto it that it doesn’t deserve. We need to call this what it is, which is an attempt to extort universities, to shut down free expression on campuses, to impose ideological restrictions under another name.”