Last year turned out to be a tumultuous one for higher education, with institutions buffeted by the Trump administration’s sweeping federal research cuts, unprecedented intrusion into classrooms and relentless crackdown on diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives and speech rights.

In response, campus leaders engaged with lawmakers behind closed doors, spent heavily on lobbying and co-signed higher education associations’ efforts to fight government policies that threatened academic freedom and their institutional missions. But few objected publicly. For the most part, college presidents watched in silence.

Experts say that’s not surprising; university leaders are caught in a unique moment—squeezed between faculty and students demanding action and boards and lawmakers intent on punishing those who speak up.

“Unique challenges facing presidents included that difficult balance between what campus constituents wanted for presidents to say and the desires of trustees to hold very different positions, either based on pressures from legislatures or their own political beliefs,” said Teresa Valerio Parrot, principal of TVP Communications, a sector-focused public relations firm. “Often presidents found themselves in this very interesting position of trying to please internal audiences and also meet the expectations of their bosses when they weren’t congruent.”

Here’s a look at how college presidents navigated 2025—and what observers expect this year to look like for them.

Caught Unprepared

Experts said most presidents were caught off guard by the onslaught of challenges unleashed by the federal government.

Brian Rosenberg, president emeritus of Macalester College and a visiting professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, told Inside Higher Ed that last year was “traumatizing” for campus leaders who struggled “to not get snowed under by all of the challenges they faced.”

Michael Harris, a professor of higher education at Southern Methodist University, argued that presidents had a “failure of imagination” over realizing “how damaging” policy changes would be under Trump 2.0 as the federal government shifted from a trusted partner to attack mode.

“Institutions were still trying to figure out how to navigate all the typical challenges that higher education had been facing before 2025. Those didn’t go away, but then you add on to it the federal landscape changing virtually overnight and continually changing,” Harris said. “When you’re trying to make decisions by which judge has frozen which policy or what might be coming out next, or a Dear Colleague letter that doesn’t match what the logical legal interpretation would be, that’s a challenging environment for anybody, much less a college president.”

At the same time, many leaders were also navigating financial woes, an upended athletics landscape and protests against ICE raids and international student visa crackdowns.

Lost Jobs, Stymied Searches

Institutions and individual presidents alike were caught in the political crosshairs in 2025, leading to a litany of federal and state investigations, resignations and the occasional legal showdown.

Multiple presidents targeted by federal or state lawmakers stepped down in 2025, including Michael Schill at Northwestern University and Jim Ryan at the University of Virginia. Both had drawn scrutiny from the federal government: Schill for his handling of pro-Palestinian protests and Ryan for allegedly failing to dismantle diversity, equity and inclusion programs fast enough. Others, like Mark Welsh at Texas A&M University, were pushed out by pressure from state politicians.

Welsh was caught in a flap between Melissa McCoul, an English instructor, and a student in her children’s literature class who objected to the professor’s statement that there are more than two genders, citing an executive order from President Trump that recognizes gender only as male and female. Welsh initially resisted firing McCoul until the student tagged a Republican lawmaker, who published a video of the incident, ratcheting up pressure on both Welsh and McCoul. Ultimately, Welsh fired McCoul as the controversy swirled and other Texas politicians piled on.

Although Welsh gave state lawmakers what they wanted, it was too late to save his job.

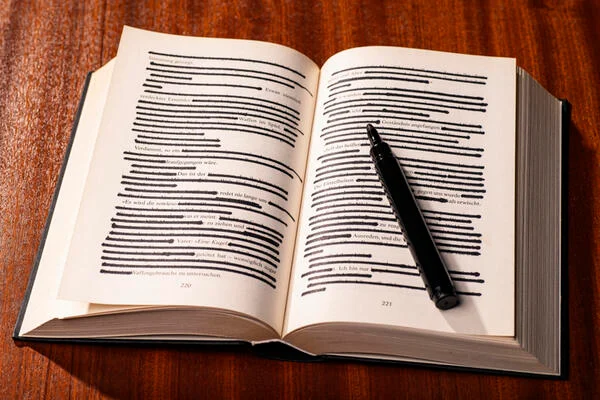

He resigned under pressure and was replaced by interim president Tommy Williams, a former Republican lawmaker. In his first few months on the job, Williams sparked controversy after Texas A&M censored a philosophy course; officials told the professor he could not teach Plato in a class on contemporary moral problems because it conflicted with university restrictions on topics of race, gender and sexuality. (Williams has since noted the university is not “banning Plato altogether.”)

More recently, Texas A&M canceled a graduate ethics class after a professor said it would be impossible to specify the precise timing or manner in which topics of race, gender and sexuality would arise.

Texas A&M did not respond to a request for comment from Inside Higher Ed.

Judith Wilde, a research professor at George Mason University who studies presidential searches and contracts, wrote by email that 2025 had “unusually high” turnover both at the presidential level and among other high-ranking academic leaders. She noted that amid the current political volatility, “some institutions seem to be using an interim leader to buy time as they consider their political exposure as well as try to avoid committing to a long-term hire.”

Similarly, Rosenberg pointed to the mid-2024 elevation of Harvard University president Alan Garber from interim to permanent status as an example of a college making a relatively safe choice and sidestepping the internal and external criticism that would inevitably accompany an executive hire. He also noted that Columbia University recently extended its presidential search.

“Nobody wants to do a search right now, particularly at these elite privates, because of the kind of scrutiny it will draw and the difficulty of hiring the right kind of person,” Rosenberg said.

Who Gets to Be a President?

Last year also saw significant presidential hiring drama, such as when the Florida Board of Governors rejected Santa Ono as the next president of the University of Florida, even though the institution’s Board of Trustees voted unanimously to select him as their next leader. The FLBOG largely shot down Ono’s selection over concerns about his past support of diversity, equity and inclusion efforts, which he unsuccessfully sought to downplay.

Wilde said that reflects a shift not only in who is being hired but also in the fact that “the search itself is no longer the deciding factor in choosing a president” as boards lean into performative public vetting. Now “whether the president can survive the ideological gauntlet” is what matters most in hiring, she said.

She suspects such factors may prevent traditional academics from applying for presidencies.

At UVA, the Board of Visitors tapped an internal candidate, business dean Scott Beardsley, who reportedly scrubbed multiple references to DEI initiatives from his résumé during the search process. (Critics have also accused Beardsley of inflating his academic profile and research output.)

Experts say such instances reflect both sector hiring challenges and the changing nature of the presidency.

“When you have a rash of poor hires, failed searches, failed presidencies, at some point we have to acknowledge that’s not individual failures, it’s systemic failure,” Harris said. “I think we need to acknowledge we have systemic failures in how we hire, recruit, retain, reward and support presidents. Also, the job is changing, insofar as presidents have to be more politically savvy. It’s always been a part of the job, but I feel like now that is even more so the case.”

Rosenberg agreed that a president’s political affiliation matters more than ever, especially in red states like Florida and Texas, which have hired numerous former lawmakers to lead higher ed institutions.

“It’s never been irrelevant, certainly at public institutions, but in places like Florida and in Texas, we’re basically seeing college presidents being chosen from current or former politicians. So political affiliation is important in public institutions in ways that it has never been before,” Rosenberg said.

The Year Ahead

Experts project another challenging year for college presidents owing to a difficult policy environment. But they also note a few points of optimism that presidents can build on in 2026.

Valerio Parrot said that one win from 2025 was that “presidents were able to find coalitions” and to network with other leaders in similar positions, using one another as sounding boards. Such relationships, she said, helped guide them through moments of political uncertainty. Valerio Parrot also pointed to the role higher ed associations played in pushing back on federal overreach.

Rosenberg noted Harvard’s legal victory against the Trump administration after it tried to strip the university of federal research funding, among other actions.

He wants to see more college presidents take a stand and exhibit moral courage.

“I think what they could learn is that not resisting authoritarian growth doesn’t stop it. It enables it,” he said. “You would have thought that people would have learned that from history, but apparently we have not. If you allow authoritarians to continue to expand their power without pushback, they will expand that even more. You do that long enough, and sooner or later you reach a point where you can’t push back. I think the lesson is that duck and cover isn’t working.”

Valerio Parrot urged presidents to ask themselves three questions when considering whether to issue statements: “Why them? Why now? And what is the takeaway from what they’re sharing?” If presidents choose to speak up, she argued, they need to do so in a way that does more than add noise.

While speaking up is perilous, Harris argued it’s the kind of decision presidents must weigh and strike the right balance in execution.

“This is where I think presidents are in a no-win situation. If they spoke out as forcefully as their faculty wanted, they would be in an untenable position,” he said. “At the same time, if you’re not willing to advocate for the core values of your institution, then what are you doing at the top?”