Dive Brief:

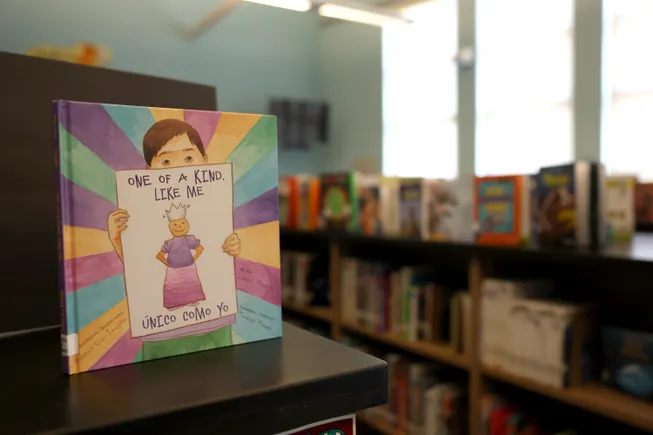

- In the fourth school year since book bans proliferated on local school board levels, districts are now also facing federal and state pressures to ban books, according to a report released Oct. 1 by PEN America, a nonprofit that advocates for free speech.

- The organization noted that federal efforts to influence education issues are repeating state and local book banning rhetoric, which it calls a “a new vector of book banning pressure.” For example, the parental rights movement behind book banning is being repeated at the federal level in executive orders leading to the reversal of diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives and LGBTQ+ inclusion.

- The escalating book censorship campaigns usurp educators’ time that would otherwise be used for instruction, can subject them to harassment, and also leads to them spending long hours cataloging books and dedicating more administrative time to comply with bans, the report said. Districts are also incurring “significant” legal costs navigating lawsuits.

Dive Insight:

There were 6,870 instances of book bans across 23 states and 87 public school districts in the 2024-25 school year, according to PEN America. That totals 22,810 cases of book bans across 45 states and 451 public school districts since the organization began tracking the issue in July 2021.

PEN America’s definition of “bans” includes books that have been taken off the shelf pending investigation, and any other steps taken against books as a result of parent, community or government pushback leading to limited student access.

“From a birds’ eye view, school districts today are surrounded by multiple and persistent local, state, and now federal pressures to ban books, with diminishing reasons not to,” the report said.

At the federal level, the Trump administration’s U.S. Department of Education in January rescinded Biden-era guidance. That guidance had warned school districts that they could violate civil rights law by implementing book bans, and it said that removing “age-inappropriate” books from schools is a parent and community decision that the federal government “has no role in.”

At the same time, the department dismissed 11 civil rights complaints related to book bans.

It also eliminated the position of a book ban coordinator, created by the Biden administration in 2023 to develop training for schools on navigating book bans.

Four years after the initial wave of book bans swept localities, communities and educators “have been conditioned to expect book challenges and bans as part of the U.S. education system,” PEN America said in a statement.

“A disturbing ‘everyday banning’ and normalization of censorship has worsened and spread over the last four years,” said Kasey Meehan, director of PEN America’s Freedom to Read program, in an Oct. 1 statement. “The result is unprecedented.”

Districts are responding by removing books to comply out of fear of losing funding, staff being fired or harassed, and sometimes having police involvement, the organization said.

In an August 2024 report, the Knight Foundation found in a survey of over 4,500 adults that two-thirds of Americans oppose book restrictions in schools and even more are confident in public schools’ book selection. More Americans said in that survey that it was more concerning to restrict students’ access to books with educational value than it was to provide them with access to books that have inappropriate content.

However, a majority (6 in 10) also said that age appropriateness — as opposed to parents’ political views, religious beliefs or moral values — was a legitimate reason to restrict students’ book access. The survey included responses from over 1,100 pre-K-12 parents.