Like most of my colleagues in art history, English, history, modern languages, musicology, philosophy, rhetoric and adjacent fields, I am concerned about the current crisis in the humanities. Then again, as a student of the history of the modern university, I know that there haven’t been too many decades over the last 150 years during which we humanities scholars have not employed the term “crisis” to portray our place in the academy.

Our Greek forebears, as early as Hippocrates, coined the term “kρίσις” to describe a “turning point”; kρίσις, a word related to the Proto-Indo-European root krei-, is etymologically connected to practices like “sieving,” “discriminating” and “judging.” In fact, the most widely mentioned skill we humanists offer our students, critical thinking, originates from the same practice of deliberate “sieving.” Thus, when we call ourselves critics and write critical theory, we admit that crisis might just be our natural habitat.

What’s Different This Time Around?

A look at the helpful statistics provided by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences indicates that this latest crisis in humanities enrollments and degree completions is not like the previous fluctuations in our history, but more foundational. Things sounded bad enough when a state flagship like West Virginia University slashed modern languages (and math!) two years ago. But when that beacon of humanistic learning, the University of Chicago, pauses Ph.D. admissions across all but two of its humanities programs, we know the crisis is existential. Wasn’t it Chicago’s Kalven report that once stated boldly, and for the entire nation, that the university was “the home and sponsor of critics”?

Cultures of Complaint, and a Pinch of Hubris

Feeling powerless in the face of dwindling enrollment and support for our disciplines, some of us have resorted to digging up conspiracy theories, perhaps because, as Stanley Fish opined, in the psychic economy of academic critics, “oppression is the sign of virtue.” The tenor of such virtue-signaling complaints is that an unholy alliance of tech and business bros and their programs, together with politicians and academic leaders, promote only “useful” disciplines and crowd out interest in the humanities.

I think intellectual honesty would demand we remember that it was the humanities, custodians of high-culture education (Bildung), that once upon a time crowded out the applied arts, crafts and technologies, accusing them of lacking intellectual depth. Humanistic Ivy League and Oxbridge schools championed the classics, philosophy and literary studies as “liberal” and sneered at professional education in the “mechanical arts” (engineering, agriculture, business, etc.) as “servile.” When the humanities (and natural sciences) faculty at these elite colleges refused to open their classist “gentlemen’s education” to larger publics, land-grant universities and technological institutes emerged to increase access and to educate teachers, lawyers and engineers.

Could it be that today’s humanists still retain some of this original hubris toward technical, vocational and applied training, which makes the current inversion of disciplinary hierarchy even tougher to accept? Are warnings against instrumentalizing the humanities for economic gain (Martha C. Nussbaum, Not for Profit) or applying them to support vocational or technical disciplines (Frank Donoghue, The Last Professors) echoes of such hubris? Will this mentality, based on the knowledge economy of the late 19th century, convince today’s students to work with us?

Angsting About Ancillarity

The modernist poet W. H. Auden, in his book-length poem about anxiety, wrote that “We would rather be ruined than changed / We would rather die in our dread / Than climb the cross of the moment / And let our illusions die.” For sure, some among us deny the signs of the time, yearning for the golden days when humanities departments were ever expanding, arguing that an essential third Victorianist (focusing on drama) be added to the colleagues already focusing on fiction and poetry. If these golden days ever existed (in the early 1970s?), they are gone now. Nostalgia for the simulacrum persists.

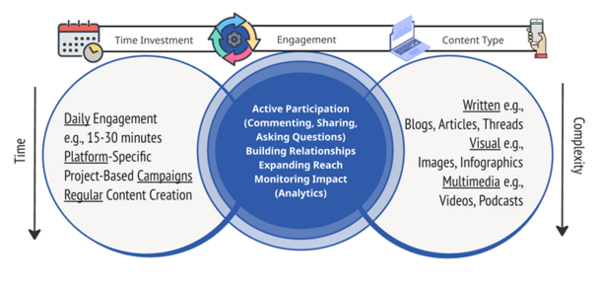

Closer to reality, many colleagues in the humanities have been “climbing the cross of the moment,” adapting to the inversion of disciplinary hierarchies at our institutions and accepting the mandate to show at least some measurable outcomes instead of our beloved unquantifiable humanistic critique. We have been aligning with the new lead disciplines by creating a vast infrastructure of certificates, degrees, journals, book series and organizations in the medical, health, digital, environmental and energy humanities, in science and technology studies, computational media, and music technology.

However, as Colin Potts observed, when we partner with our colleagues in these better-funded and high-visibility disciplines, we are rarely “co-equal contributors.” We are like alms seekers, condensing our lifelong training and knowledge into an ethics, civics and policy module required for our partners’ accreditation, or infusing technical writing and communication skills into a STEM curriculum to amplify their majors’ impact. These collaborations offer a modicum of recognition and an honorable mention in a holistically minded National Academies consensus report. But they also make us feel dreadfully ancillary.

Institutional strategic plans that exalt the value of the humanities with terms like “cornerstone,” “core” and “heart” only deepen our suspicions, especially when our budgets don’t match the performative strategic grandiloquence. From the medieval through the 18th-century university, the humanities suffered the trauma of being “handmaidens to theology” (ancillae theologiae), then the doctrinal master discipline. Now, technology has taken theology’s place, and we are once again “pleasant (but more or less inconsequential) helpmeets.” Trauma redux.

Hyperbole Won’t Help

In an existential crisis, hyperbole in the defense of our field no longer feels like a vice. Therefore, some of us now claim that the end of the humanities heralds the end of humanity and human civilization. Brenna Gerhardt, for example, warned that, because of the 2025 funding cuts to the National Endowment for the Humanities, “we may find that a society that forgets to ask what it means to be human forgets how to be one.”

Similarly, the 2024 World Humanities Report asserts that “the humanities are of critical importance” at a time when the “world and planet [are] under duress” and in dire need of “tools and concepts that will foster change and help us live under these shared, if still uneven, conditions.” These kinds of well-meaning statements, and the desperate daily news item (preferably from Oxbridge) amplifying our relevance and adaptability, burden the academic humanities with a responsibility incommensurate with the cultural and educational work we can perform. Their claim that “either you support the humanities, or inhumanity prevails” scares only us, but nobody else. As the authors of WhatEvery1Says: The Humanities in Public Discourse find, “The humanities appear to the public to be siloed in universities (unlike the sciences).”

This I Believe

If the previous paragraphs didn’t sound resilient and hopeful enough, please remember that my first obligation as a humanist is to be a critic, not a cheerleader. I believe that the humanities do have an important place in the ecosystem of higher education and at each university, that integrating STEM and liberal arts practices increases student success and leads to better research and scholarship, that humanistic considerations contribute to a more just and benign world, and that we need to continue our important work in core education.

However, I don’t think that we academic humanists have sufficient standing to make hyperbolic claims about what we can achieve. Just consider: Have we ever advanced how many majors and faculty positions would be enough to keep the world humane and civilized? Have we, as Roosevelt Montás asks in Rescuing Socrates, ever overcome the “crisis of consensus … about what things are most worth knowing”? And should we lecture our STEM colleagues on ethics and gender equity when, as recently as 2019, fewer than one-third of tenure-track faculty and fewer than one-fourth of non-tenure- track professors in U.S. philosophy departments were women?

We humanists are really good at asking critical questions, “sieving,” “discriminating” and “judging” at the highest levels of abstraction, but we are not so good at offering solutions. When we do, they often come from the same intellectual heights that have alienated us from undergraduate populations and the public. In a recent essay for the Journal of Theoretical Humanities, Wayne Stables takes us beyond hyperbole. He asks us to envision our lives and work “as if the humanities were dead,” thereby (he hopes) freeing us to consider collective action based on the likes of G. W. F. Hegel, Karl Marx, Friedrich Nietzsche, Theodor W. Adorno, Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida and Wendy Brown. He believes this kind of “critical orientation” may help us survive “the troubling interregnum” in which we now find ourselves.

While I sympathize with Stables’s call to action (though I would add Hannah Arendt, Simone de Beauvoir, Julia Kristeva, bell hooks and Judith Butler to his list), I believe it takes us back to the time when the humanities strove to be “all breathing human passion far above.”

I recommend we befriend the idea that our humanistic values and practices may relate to more public-oriented and holistic goals, as exemplified by the University of Arizona’s successful degree in the public and applied humanities, which wants “to translate the personal enrichment of humanities study into public enrichment and the direct and tangible improvement of the human condition” and offers a “fundamentally experimental, entrepreneurial, and transdisciplinary” educational experience that “focuses on public and private opportunities that straddle rather than fall between purviews, or are confined by them.”

Since the introduction of this new kind of humanities program, connected with such fields as business, engineering and medicine, the number of students majoring in the humanities at Arizona has increased by 76 percent. This true kind of integrated partnership, and similar initiatives at St. Anselm College, Virginia Tech and my home institution of Georgia Tech, give me hope for a turning point—kρίσις—for the humanities in higher education.