You could read “abolishing the 50 per cent participation target” as a vote of no-confidence in higher education, a knee-jerk appeal to culturally conservative working-class voters. But that would be both a political/tactical mistake and a fundamental misreading of the policy landscape.

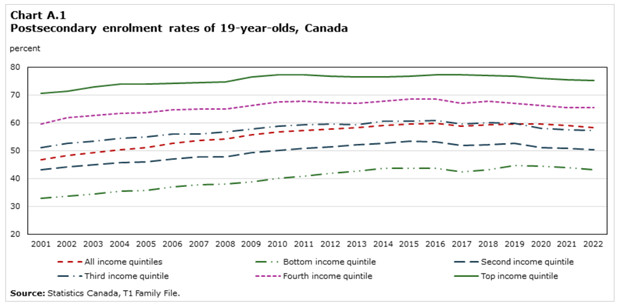

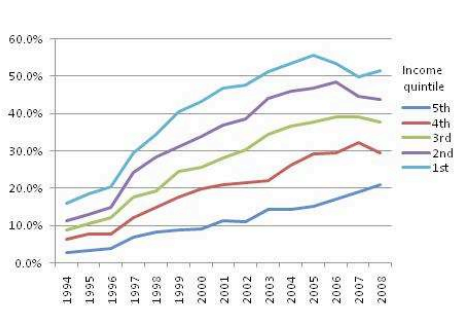

To recap: in his leader’s speech to Labour Party Conference on Tuesday, Prime Minister Keir Starmer announced that two thirds of people under 25 should participate in higher level learning, whether in the form of academic, technical, or work-based training, with at least ten per cent pursuing technical education or apprenticeships by 2040.

So let’s start by acknowledging, as DK does elsewhere on the site, that the 50 per cent participation target has a totemic status in public discourse about higher education that far outweighs its contemporary relevance. And, further, that party conference speeches are a time for broad strokes and vibes-based narrativising for the party faithful, and soundbites for the small segment of the public that is paying attention, not for detailed policy discussions.

An analysis of Starmer’s speech on Labour List suggests, for example, that the new target signals a decisive break with New Labour, something that most younger voters, including many in the post-compulsory education sector, don’t give the proverbial crap about.

True North

What this announcement does is, finally, give the sector something positive to rally around. Universities UK advocated nearly exactly this target in its blueprint for the new government, almost exactly a year ago, suggesting that there should be a target of 70 per cent participation in tertiary education at level four and above by 2040. Setting aside the 3.333 percentage point difference, that’s a win, and a clear vote of confidence in the post-compulsory sector.

Higher education is slowly recovering from its long-standing case of main character syndrome. Anyone reading the policy runes knows that the direction of travel is towards building a mixed tertiary economy, informed if not actively driven by skills needs data. That approach tallies with broader questions about the costs and financing of dominant models of (residential, full time) higher education, the capacity of the economy to absorb successive cohorts of graduates in ways that meet their expectations, and the problematic political implications of creating a hollowed out labour market in which it it is ever-more difficult to be economically or culturally secure without a degree.

The difference between the last government and this one is that it’s trying to find a way to critique the equity and sustainability of all this without suggesting that higher education itself is somehow culturally suspect, or some kind of economic Ponzi scheme. Many in the sector have at times in recent years raged at the notion that in order to promote technical and work-based education options you have to attack “university” education. Clearly not only are both important but they are often pretty much the same exact thing.

What has been missing hitherto, though, is any kind of clear sense from government about what it thinks the solution is. There have been signals about greater coordination, clarification of the roles of different kinds of institution, and some recent signals around the desirability of “specialisation” – and there’s been some hard knocks for higher education providers on funding. None of it adds up to much, with policy detail promised in the forthcoming post-16 education and skills white paper.

Answers on a postcard

But now, the essay question is clear: what will it take to deliver two-thirds higher level learning on that scale?

And to answer that question, you need to look at both supply and demand. On the supply side, there’s indications that the market alone will struggle to deliver the diversity of offer that might be required, particularly where provision is untested, expensive, and risky. Coordination and collaboration could help to address some of those issues by creating scale and pooling risk, and in some areas of the country, or industries, there may be an appetite to start to tackle those challenges spontaneously. However, to achieve a meaningful step change, policy intervention may be required to give providers confidence that developing new provision is not going to ultimately damage their own sustainability.

But it is on the demand side that the challenge really lies – and it’s worth noting that with nearly a million young people not in education, employment or training, the model in which exam results at age 16 or 18 determine your whole future is, objectively, whack. But you can offer all the tantalising innovative learning opportunities you want, if people feel they can’t afford it, or don’t have the time or energy to invest, or can’t see an outcome, or just don’t think it’ll be that interesting, or have to stop working to access it, they just won’t come. Far more thought has to be given to what might motivate young people to take up education and training opportunities, and the right kind of targeted funding put in place to make that real.

The other big existential question is scaling work-based education opportunities. Lots of young people are interested in apprenticeships, and lots of higher education providers are keen to offer them; the challenge is about employers being able to accommodate them. It might be about looking to existing practice in teacher education or health education, or about reimagining how work-based learning should be configured and funded, but it’s going to take, probably, industry-specific workforce strategies that are simultaneously very robust on the education and skills needs while being somewhat agnostic on the delivery mechanism. There may need to be a gentle loosening of the conditions on which something is designated an apprenticeship.

The point is, whatever the optics around “50 per cent participation” this moment should be an invigorating one, causing the sector’s finest minds to focus on what the answer to the question is. This is a sector that has always been in the business of changing lives. Now it’s time to show it can change how it thinks about how to do that.