- This is an edited version of a speech giving by Vivienne Stern, Chief Executive of Universities UK, to the HEPI Annual Conference on Thursday 12 June.

Thank you, Nick, for the invitation to speak today.

In a somewhat pathetic attempt to prove the utility of my degree in English Literature, I once learned that the way to prove the validity of your argument was to back it with reference to a work of literature, preferably by someone who was good and dead.

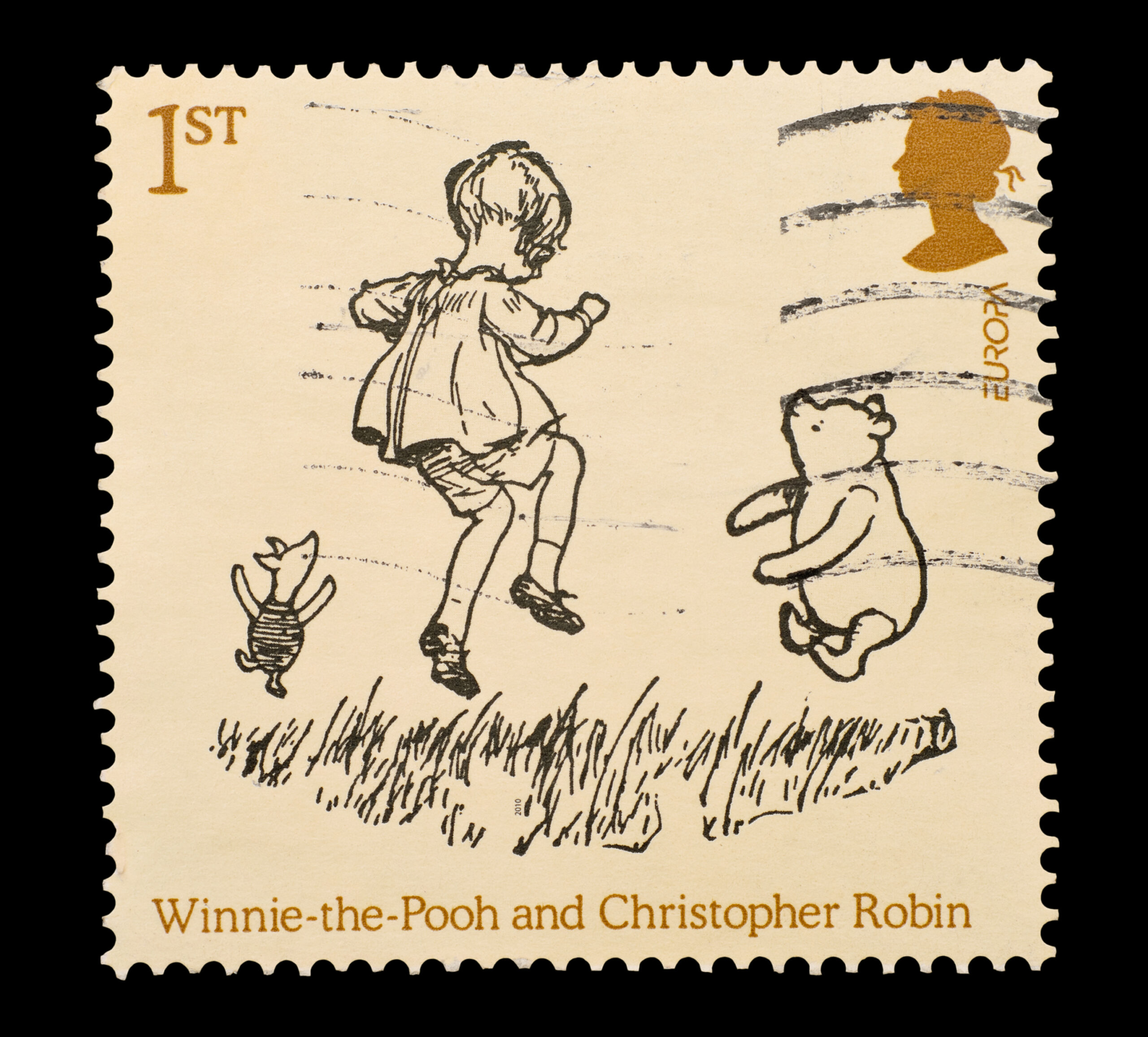

And so, I want to start with the opening lines of Winnie-the-Pooh.

Here is Edward bear, coming downstairs now, bump, bump, bump, on the back of his head, behind Christopher Robin. It is, as far as he knows, the only way of coming downstairs, but sometimes he feels that perhaps there is another way, if only he could stop bumping for a moment and think of it.

How like being a Vice Chancellor.

Most mornings, I imagine you leaping out of bed, full of the joys of spring and filled with a sense of possibility. Between that point and, let’s say, breakfast, you probably find yourself getting hit on the back of the head by 20 or 30 things that will, unequivocally, need dealing with. It is not dull. But this constant stream of new bumps can make it difficult to take a step back and think. Where is this all heading?

We are challenged on both sides of the political spectrum, and there is a curious degree of political consensus around some of the major issues. Anxiety about whether the massification of higher education has gone too far; whether too many students are studying for degrees that have limited value; whether this represents a good use of public money in the form of the loan write-off, and that some of these students would be better off doing something else. There is a concern from both right and left about the degree to which the sector has become increasingly characterised by competition which seems to serve no one well.

Research, currently being undertaken on behalf of Universities UK by Stonehaven and Public First, has illuminated public concerns about the financial motives at play in the sector – a sense that somehow students and graduates are getting screwed by the system – bound up with widespread dissatisfaction about the state of the economy, public services and a growing anxiety that the future for us and our children is one of inevitable decline.

This is underpinned, both in the current government and on the right of the political spectrum by that old conviction that there are ‘good universities’ – generally confused with the Russell Group – and ‘other universities’ which are generally suspect. On the upside, from the Chancellor on down, there is a genuine belief in the power of universities to power the economy and individual opportunity. Government wants more of the good stuff. But in both government and the official opposition, questions are being asked about public funding could be directed in a more targeted way to support, to encourage and incentivise those things which public and politicians would like to see more of – and weed out the stuff they are less convinced by.

I have told you nothing that you don’t already know.

The question is, what are we going to do about it?

When I started in this job, nearly three years ago, I thought I knew what to expect. A few months in I found myself saying to my husband ‘What on earth was I thinking? I used to have this lovely job, swanning around the world listening to Ministers in other governments tell me how wonderful our university system was. It was like wandering into the bottom right-hand corner of the Hundred Acre Wood – Eeyore’s Gloomy Place (rather boggy and sad).

How do we get out of it?

One path leads us deeper into the bog.

Political distrust and pressure on public finances, coupled with a belief that somehow other parts of the education system have more to offer, leads to the continuing erosion of funding -in all four nations of the UK.

You have less money to teach and support students; while scrutiny, scepticism and expectations continue to grow. This forces you into increasingly competitive measures – increased risk appetite in areas like international recruitment, transnational education (TNE) and franchising, fiercely competitive recruitment behaviour which hobbles one university at the expense of another. In research, the paramount need to remain internationally competitive and to retain rank position drives more and more universities deeper and deeper into financial difficulty. The only way out is to press the pedal on international recruitment, to the extent that the Home Office will let you.

This feeds public and political distrust and a sense that something is irretrievably broken here. Even tighter immigration controls follow. More regulation of outcomes and franchising. All sorts of people start to think your problems are of your own making, and that they have simple solutions: whether that’s cutting or capping student numbers, or deciding what to fund or not fund, to determining which universities do research and which do not.

This is the path we’re on.

At UUK, we have spent the last two years trying to map the other path – what gets us out of this bog, and back to the bit of the forest with more of the bees and butterflies?

That was the point of the Blueprint, which we published nine months ago.

There are many people who think that the answer is just explaining ourselves better. I partly agree with them. Of course, we should do more to increase public and political understand of the fantastic work that universities do in all sorts of areas. I see this stuff every single day, in universities of all types, and in all parts of the country. At UUK, we’ve been doing much more of this front-footed stuff through a series of interlocking campaigns to reinforce three key messages: a degree is an overwhelmingly good investment for most graduates; universities power local, regional and national economies; and that universities are a vital national asset.

We need to do more of this, and more effectively. We’re working closely with communications teams in universities to help us.

But I don’t think doing more of this is going to solve the problem or change the path we’re on.

And I don’t think that we can counter negative perceptions of the sector by explaining why they are wrong.

That was the point of the Blueprint. We took a good hard look at what was working well, and what could be better. We enlisted critical friends to provide challenge, and to try to keep us focussed not what on we needed from the Government, but on what the country needed from us.

And we are following through: there are far too many recommendations in the Blueprint – but we are delivering on the most significant ones already, and we can see evidence of the influence of the agenda we set in the Westminster government Higher Education Reform agenda.

The Transformation and Efficiency work is one part of this. A couple of weeks ago we published the first outputs of that work, describing seven opportunities which would help the university system move towards a New Eara of Collaboration. We will shortly publish the next output; a guide to what we are calling ‘Radical Collaboration’ produced by KPMG and Mills and Reeve. JISC sharing with the sector outline business cases for three major areas of sector-level cooperation: procurement; shared business services; and collaboration to sustain vulnerable subjects.

Step by step, we’re trying to pick our way towards the other path through the woods. A route which starts with an attempt to be objective and, where necessary, self-critical; not defensive when faced with criticism, but confident enough to listen to it and respond thoughtfully and proactively. To build pride in what our universities currently represent in the national self-image, and to present them as a reason for optimism about our country’s future. I’d like us to be able to capture some of the excitement you all encounter in labs and seminar rooms – students and staff who are busy discovering something new, and can’t wait to tell other people about it.

At heart, what I think we are working towards is a proposition that the university system should not resist the growing clamour for change, it should own it. We should lean into change. We should remind people change is part of our story: that every so often, the university system goes through a major evolution: think of the 1850s and the establishment of a generation of technical institutes for the education of working men, to the radical decision to start admitting women, to the 60s White Heat of Technology universities; to the removal of the binary divide and the age of massification.

Our universities are constantly changing, and change is good.

Like the rings in a tree, these moments of transformation happen periodically as the sector grows. But they happen around a recognisable core. If a scholar from the 1400s pottered through a wormhole in time, they would recognise what is happening in our universities – the pursuit of knowledge and its transmission within a scholarly community – but the way that successive eras of change have left their marks would tell the history of the sector.

Seismic social changes, which have changed who is in our universities: what they study, how they study and how closely we work with wider society, industry and public services.

So, here’s the thing. I believe we are going through one of those periods of change which leaves a mark. That we’re entering a new era and we’re the lucky folks who get to try to work out what the change will be.

What will enable this great university system to go from strength to strength?

But we’re not alone in thinking that this is a moment where change is needed. There is a window, which is open for now, but is not going to stay open too long.

In July, the Westminster government will publish its Higher Education Reform strategy, embedded in a post-16 White Paper. At some point, either alongside that or slightly later in the year, the Department for Science and Technology (DSIT) will set out their vision for the research system and the university place within it.

The current line of thought tends towards differentiation of mission; specialisation and a more directive approach to the distribution of scare public funds to support national priorities.

An extreme version of this might result in universities being put into boxes; constrained in their mission; to government picking winners and losers – from amongst institutions, or types of institution, or from amongst subjects.

The traditional metaphor here requires jam. Since we are in the Hundred Acre Wood, I will substitute jam for honey.

It will be from thinly spread honey to honey concentrated in a smaller number of places, or used for a smaller number of things. The strategic priorities grant, made up of about 30 tiny honey pots, will see quite a bit of smashing up. A smaller number of bigger pots will take its place. Government will use these to incentivise and support the things it wants to see. Since we don’t anticipate there being, overall, much more honey, it implies that some will end up on bread and water.

I am going to get myself out of a sticky mess by dropping the metaphor.

I am instinctively a bit jumpy about Ministers deciding what universities should and should not do, simply because I have worked with quite a lot of them.

Can we come up with a compelling vision, behind which we can enlist the support of both universities themselves, and the government alongside it?

The Blueprint and the Efficiency and Transformation Taskforce are trying to point the way. They set out:

- A conviction that we should not turn back on the road to massification: that although there are many who doubt it, we should keep going, until your background is not the most likely determinant of whether or not you go to university.

- A belief that further expansion should not necessarily be more of the same: we can work to present choices, illustrating the many different ways universities already offer higher education. From degree apprenticeships, fully online, blended, and accelerated provision, to courses developed for specific employers in partnership with them. Presenting the three-year degree as one option amongst many for those who want a higher education – but a positive choice with distinct and valuable features, which explain its enduring appeal.

- But we could lead the debate about what the LLE could become – how it could allow students and employers to club together to support professional development throughout a career, in a structured and accredited fashion.

- And while there are those who say that there is no such thing as the university system; we might assert that we should act to make sure that we don’t see a slow falling apart of something that should be a system, by an over-emphasis on competition within a market. This county needs universities which are capable of filling a range of needs – from world leading specialist institutions, like the Courtauld Institute which I will visit later today, or the Royal College of Music; to the post graduate institutions which don’t appear in the rankings because NEWS FLASH the rankings don’t capture post graduate institutions; to the small community based universities which are often church foundations, and which focus on a public service mission. We need these things just as we need the enormous powerhouses that are our great dual-intensive and research-intensive institutions. If it can be argued that we don’t have a system, we should look to change that.

- We should acknowledge again and again that this country is in a bit of an economic funk and that, as it has done many times before, the university system will put its shoulder to the wheel to help turn that around. That we’re open to being more forensic in our analysis of what is effective, to spreading the best practice more widely, to being held to account. What I really mean is that we should stop just producing studies on our economic impact, which the Treasury ignores, and work with government to develop a shared understanding of the economic value created by the university system, which we could actually use – as we have HEBCI and REF – to influence behaviour and improve what we do.

- Above all, we have an emerging conviction that universities can and should collaborate more – both to be more efficient and to be more effective in their collective mission. We should be willing to think radically about this. The next phase of the Transformation and Efficiency work will be focussed on how we might support this direction of travel in very practical ways.

And the role for Government? Perhaps more Christopher Robin than AA Milne. More ‘in the forest with us, finding our way together’, than ‘sitting in an office in Whitehall and deciding who does what’.

But we do want Government in there – most importantly we want Government to recognise that there is a public interest in the way this system works. That public funding can play a role in smoothing the rough edges of the market and correcting for its failures, and that have a responsibility alongside the sector itself for the stewardship of the system.

Going back to Winnie the Pooh has been a pleasure. I am going to end where I began, as the book itself does, with the image of Winnie, going upstairs this time, ankle first, gripped by the little fist of Christopher Robin. Let’s stop bumping a while, so we can think.