This blog was kindly authored by Mark Jones, Executive Vice President – Education, TechnologyOne.

Having worked with higher education institutions globally for three decades, I’ve seen policy-driven transformation succeed and fail. The difference comes down to whether institutions treat fundamental change as a strategic and commercial opportunity, or merely as a compliance burden.

Across UK universities, conversations are increasingly centred on what the Lifelong Learning Entitlement (LLE) will mean in practice. The LLE fundamentally restructures how higher education is funded and accessed. Learners will be able to study modular provision at levels 4 to 6 in government-prioritised subjects, pay for individual credits, accumulate learning over decades, and transfer credits between providers.

The policy intent – making higher education more accessible – is clear. For institutions built around three-year undergraduate programmes, delivering on that requires more than administrative adjustment. It demands a rethink of curriculum design, digital systems, academic regulations and student support models.

A technology inflection point

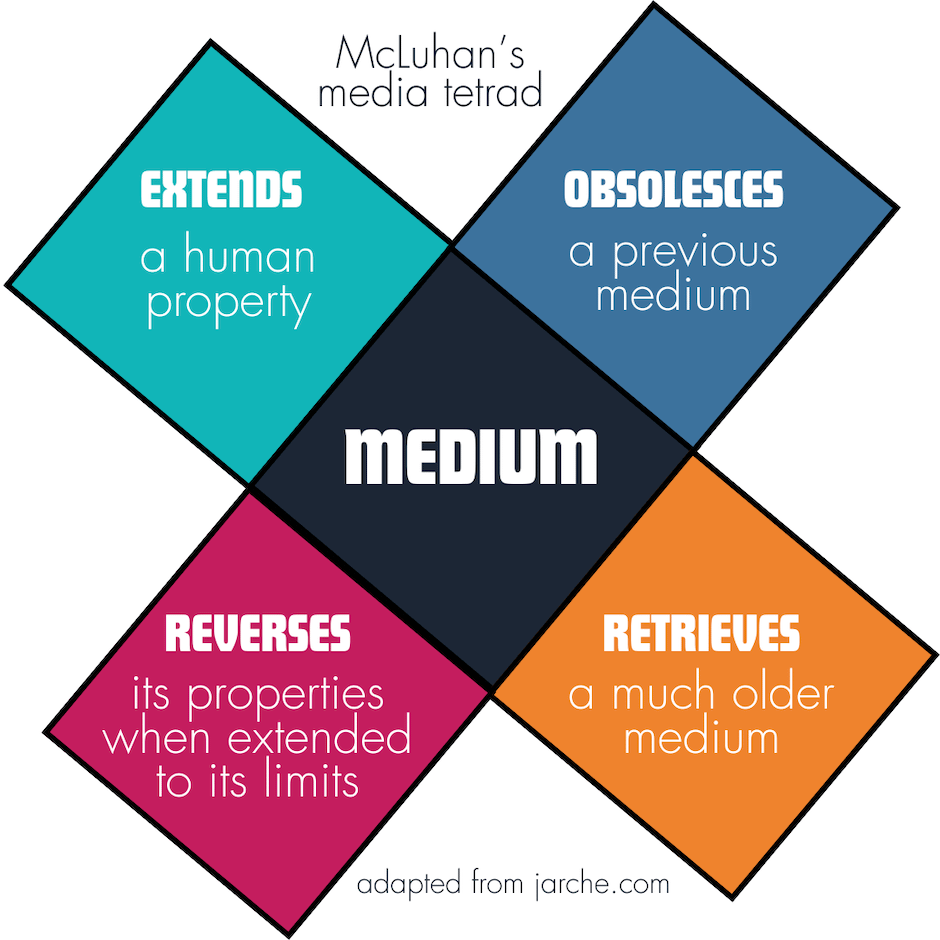

The LLE is more than a policy change. It represents a technology inflection point for higher education. For years, institutions have made incremental adjustments to systems designed for cohort-based, September-to-June academic cycles. The LLE exposes the limitations of those systems.

Institutions will need to track lifetime credit accumulation across multiple providers, process granular payments that may be months or years apart, verify external prerequisites in real-time, and maintain learning relationships that span decades rather than discrete degree programmes.

This creates space for innovation. The challenge is not simply to adapt existing platforms, but to reimagine student record systems, finance integration, and learner engagement from the ground up. The technologies that enable personalised digital experiences in sectors such as media streaming or retail banking offer relevant models. International developments – for example, micro-credentials in Australia – provide both cautionary tales and promising precedents.

The question shifts from ‘How do we make current systems cope?’ to ‘What would we build if we designed for modular, lifelong, multi-provider learning from the outset?’

The market waiting to be served

The demand signals are clear. UCAS 2025 data shows UK mature acceptances (aged 21+) have declined 3.3% to 106,120, with steeper drops among those aged 30 and over. Meanwhile, 31% of UK 18-year-olds now intend to live at home while studying (89,510 students, up 6.9% from 2024), driven by affordability constraints.

The Post-16 education and skills white paper explicitly recognises the need for workforce upskilling at scale. Career transitions require targeted learning rather than full degrees and learners need options that fit alongside work and caring responsibilities.

The technology enabling this market – flexible enrolment, credit portability, lifetime learner accounts – represents a fundamental refresh of how higher education operates digitally. The LLE removes the policy barriers. The remaining question is whether institutions can build the infrastructure to deliver on the opportunity.

The curriculum challenge that unlocks it

Serving this market demands more than breaking degrees into smaller units. Each module must function as both a standalone learning experience and as a component that can stack with credits from other providers. Prerequisites must enable learners to navigate pathways independently. Assessment models must work for twelve-week episodes rather than three-year relationships.

Academic regulations designed for continuous programmes need to adapt to episodic engagement over decades. Student services built around sustained relationships must be reimagined for twelve-week presences. These aren’t minor adjustments; they’re fundamental policy framework redesigns.

Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) becomes central rather than peripheral. The issue is not whether institutions can scale existing processes, but whether they can reimagine how learning is valued when it originates elsewhere.

Timeline realism

LLE applications open in September 2026. For institutions targeting January 2027 launches, timelines are extremely tight. Across the sector, universities are planning phased September 2027 launches with limited subject scope, rather than ambitious early rollouts that risk operational failure.

Institutions making meaningful progress are treating LLE as a strategic transformation requiring executive vision. They are testing actual workflows, allocating dedicated resources, and making deliberate scope decisions that acknowledge building capability takes time. Importantly, they’re approaching LLE as an opportunity, not just an obligation.

The transformation ahead

The LLE creates space for institutions to rethink digital infrastructure fundamentally rather than incrementally. The most successful technology transformations occur when external pressure aligns with internal ambition – when ’we have to change’ meets ‘here’s what we could build’.

Institutions approaching this purely as a compliance exercise experience compressed timelines and onerous requirements. Those that view it as an innovation catalyst find that it justifies investments in modern, integrated platforms that have been deferred for years. It enables a more ambitious question: ‘What would a student system designed for lifelong, modular, multi-provider learning actually look like?’

The opportunity to serve learners historically excluded from higher education is genuine. So too is the opportunity to modernise infrastructure that has struggled under incremental adaptation. The sector’s challenge is translating policy ambition into operational reality for institutions, students, and the communities higher education serves. Those that thrive will be the ones that treat the LLE as permission to innovate, not just an obligation to comply.

These implementation challenges and more will be explored at TechnologyOne Showcase London on 25 February at HERE & NOW at Outernet, featuring an executive panel with voices from UCISA, ARC, HEPI, SUMS, and institutional leaders discussing how governance, culture, technology, and commercial strategies need to adapt to this new policy landscape. Register for TechnologyOne Showcase here.