Schools that train hairstylists, dental assistants and health aides will be able to keep getting federal student loan dollars even if the professionals they turn out don’t end up earning any more than a high school graduate.

That’s because programs like those, which don’t end in a college degree, were granted an exemption from new accountability measures under President Donald Trump’s ”big, beautiful bill.”

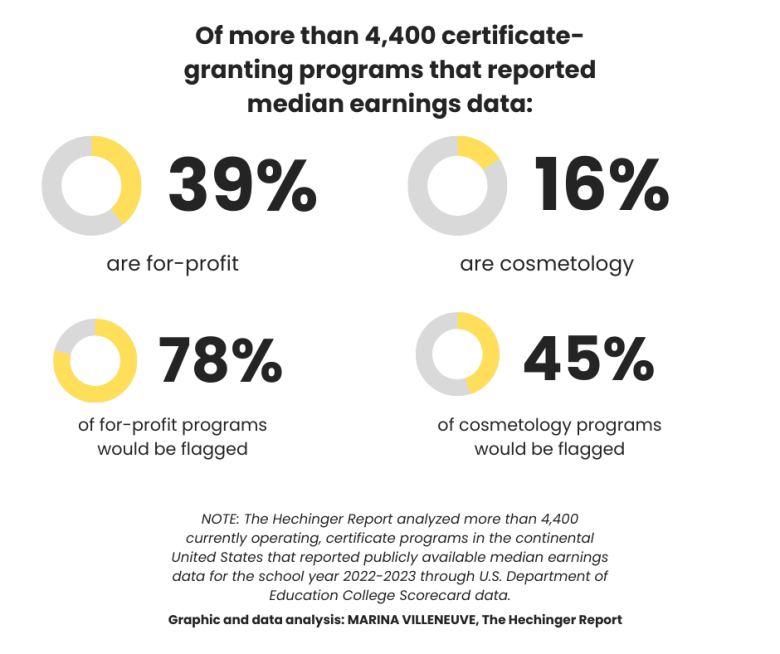

A Hechinger Report analysis of federal data found at least 1,280 such certificate programs could have been at risk of their students losing access to federal student loans — but a successful lobbying effort excluded them from the accountability measures.

Related: Become a lifelong learner. Subscribe to our free weekly newsletter featuring the most important stories in education.

Under the new law, most graduates of associate, bachelor’s and graduate degree programs must earn at least as much as someone who has only a high school diploma. If programs fail to hit that benchmark for two out of three years, their students will no longer be eligible for federal student loans. (And the schools must warn students of this possibility if they miss the mark for just one year). Without that borrowing power, many students could not afford to attend. And without those students, some of the schools might not survive.

Using the table below, see which certificate programs might have been flagged under the Trump law if not for the exemption. If graduates of a particular program ended up earning less than adults with only a high school diploma, that program could have faced losing eligibility for federal student loans under the Trump law.

Methodology

What exactly does the “big, beautiful bill” call for?

The legislation requires the Department of Education to compare earnings of working adults who have only a high school diploma to the earnings of adults four years after they complete a degree program or graduate certificate. If a postsecondary program’s graduates fail to outearn adults with only high school degrees for two out of three years, students can no longer obtain federal student loans to attend that program.

The law also sets up an appeals process and a way for programs to apply to regain eligibility for federal student loans.

What data was analyzed?

The law directs the education secretary to use census data to calculate median earnings for working adults with only a high school degree in the state where a program is located. The Department of Education will release regulations that spell out exactly how to do that math. For example, the law does not spell out whether it will look at census data averaged out over 12 months or a longer period of time.

For earnings data for high school graduates, The Hechinger Report relied on calculations from the Department of Education, which were derived from the 2022 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates Public Use Microdata Sample from the U.S. Census Bureau.

To calculate median earnings for graduates, the law directs the Education Department to put together earnings data for a cohort of at least 30 graduates who received federal student aid for postsecondary education — which typically includes grants, loans or work-study. Graduates are excluded if they’re currently enrolled in another higher education program. If there are fewer than 30 students in a cohort, the Education Department can lump together several years of data to get to 30 students.

To get earnings data for graduates of certificate programs, Hechinger used a federal database known as College Scorecard. We downloaded field of study data for the 2022-23 school year. From this data, The Hechinger Report extracted information about certificate programs, at their main campuses, and included only programs that had median earnings data. The federal database suppresses earnings data for small programs. That left 4,431 currently operating certificate programs.

How was a program determined to be at possible risk of failing the accountability measure?

For each program, The Hechinger Report compared median graduate earnings to the high school graduate earnings data of the state where the program was located. If the graduates earned less, the program was considered to be at risk.

Under the law, postsecondary programs that don’t meet the earnings benchmark for one year have to inform all current students that they are at risk of losing their eligibility for federal student loans.

Are there any limitations to the data?

The “big, beautiful bill” takes online programs into account by considering whether students live in the same state where their academic program is based. Under the law, student earnings are compared with national data rather than state data when fewer than half of enrolled students live in the state where the school is located, which may be the case for online programs.

The Hechinger Report’s analysis instead compares every program with state earnings. That’s because the College Scorecard field of study data set is limited and only includes information about graduates employed within the same state as the institution, not whether enrolled students live in the same state as the program. In addition, College Scorecard data provides earnings data for all graduates without a breakdown for whether they receive federal aid.

Also, the Hechinger database looks at the available median earnings of all students four years after graduation for the school year 2022-23, regardless of the number of graduates. Though College Scorecard suppresses data on smaller programs, median earnings data is available for programs with 16 or more working graduates. The “big, beautiful bill” directs the Department of Education to instead lump together years of data to create cohorts of at least 30 students.

Contact investigative reporter Marina Villeneuve at 212-678-3430 or [email protected] or on Signal at mvilleneuve.78

This story about beauty schools was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.